In most academic CVs, there is often — among predictable things like scholarly books, articles and reviews — a clutch of unclassifiable items. The latest addition to my own is an unobtrusive acknowledgement in The New Yale Book of Quotations, as a result of a brief email exchange a few years ago with the editor, Fred Shapiro, who first published The Yale Book of Quotations, in 2006.

I’ve always been interested in quotations, and quotation (as a practice). In humanities scholarship, quotation thrives; reading and engaging with “the literature” is fundamental to academic enterprise; knowing texts well and judiciously quoting from them is assumed to be the tip of the iceberg of scholarly mastery. And getting quotation wrong is the nub of the ethical issue of plagiarism.

Quotation interests me in particular, because my own scholarship focuses on the 18th-century writer Samuel Johnson, who has for 200 years been a fruitful source of quotations: he is well-represented in all books of quotations, including The New Yale Book of Quotations. Johnson himself said about quotation: “it is a good thing; there is a community of mind in it.”

Johnson’s remark identifies the extra-scholarly significance of quotation.

There have been, in the endless stream of human discourse, spoken and written, plenty of witty or pungent remarks. But a remark only becomes a quotation when it is quoted. When a remark or a passage achieves circulation beyond its original context, it is usually because it is recognised as wise, witty or historically significant. So, quotation is a communal, non-specialist means of knowing and transmitting history and culture.

Compilers of older dictionaries of quotations — Bartlett’s, the Oxford, the Penguin — have usually occupied themselves in sourcing their selections to their origins. They have been less interested in demonstrating that each of their carefully selected (and sourced) texts has actually been circulated via quotation. At Oxford University Press, for instance, there were committee meetings at which the men (and women) of letters who worked on the editorial side of old-fashioned publishers would discuss the merits of the tracts of great poetry lodged in their synapses. It wasn’t very scientific.

How some particular short quotable text has been quoted, and how it has come to be quoted, is just as interesting a question as accurate sourcing.

There is, for instance, a great deal of discussion — if you don’t have The New Yale Book of Quotations, see Wikipedia — about the use of the phrase “the Iron Curtain”. It is usually associated with Churchill, who used the expression at least four times in 1945. But for anyone now to say “the Iron Curtain” and attribute the phrase to Vasily Rozanov (1918) or Ethel Snowden (1920), would be pedantic and misleading. It is Churchill’s use of it that has added it to our “community of mind”.

This was the issue I wanted to discuss with Fred Shapiro. He said that, “More than other quotation collectors, I have approached the question of fame quasi-scientifically.” That is, he uses internet searching and data-mining devices to see if and how much an alleged quotation has in fact been quoted.

In writing back, he also asked if I could augment his Australasian material, and suggest the most famous quotations in Australian and New Zealand “literature/culture/history”. As an Australian, living and working in New Zealand, and with a long-standing interest in the subject, I was well-placed and enthusiastic.

I looked over the earlier edition, and sent about 40 new quotations: 10 from New Zealand, 30 from Australia. When the revised book appeared in August, I was extremely curious to see which of my suggestions made the final cut. Seven were selected.

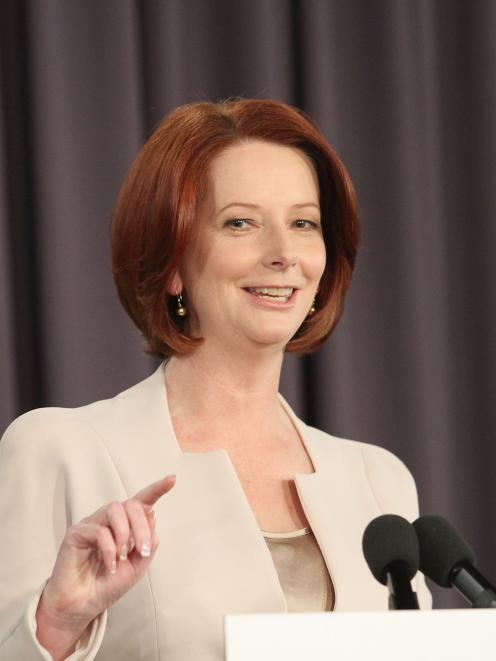

On both sides of the Tasman, prime ministers have often made memorable remarks that have been widely reported and stimulated debate. From Australia, I offered John Howard (“black armband view of history”, though he got this from historian Geoffrey Blainey), Paul Keating (“the recession we had to have”, among others: Keating was very quotable), and Julia Gillard (“I will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny ...”). From New Zealand, I thought David Lange (“I can smell the uranium on [your breath] ...”) was essential, and made a few suggestions from Rob Muldoon. Of all these, only Julia Gillard got a guernsey.

In his correspondence with me, Fred Shapiro said, “I believe a quotation dictionary should be a mixture of what is actually quoted and what deserves to be quoted.” In that spirit, the The New Yale Book of Quotations includes my few literary suggestions: one each from the bush poet and short story writer, Henry Lawson; the poet Dorothea Mackellar (“I love a sunburnt country ...”); and Dennis Glover (no prizes — if you’re a Kiwi — for guessing which two lines).

On the other hand, the editor didn’t click with my movie lines, or quotes from John Clarke (as Fred Dagg) or Barry Humphries. The transmission of pop culture between America and the Antipodes is sadly one-way, and The New Yale Book of Quotations is very American. But, as Johnson said, quotations belong to communities.

Quotation is not only more artful than bland assertion, it is more civil and generous. In the blather of blogging and tweeting and flaming and trolling and cancelling and calling out, the culture of quotation celebrates conversation rather than dogma.

It reminds us that, in a pluralistic society with a long memory, we should not always be speaking and writing, proclaiming and posturing; we need — some of us, anyway — to be reading and listening.

- Dr Paul Tankard is an associate professor of English at the University of Otago.