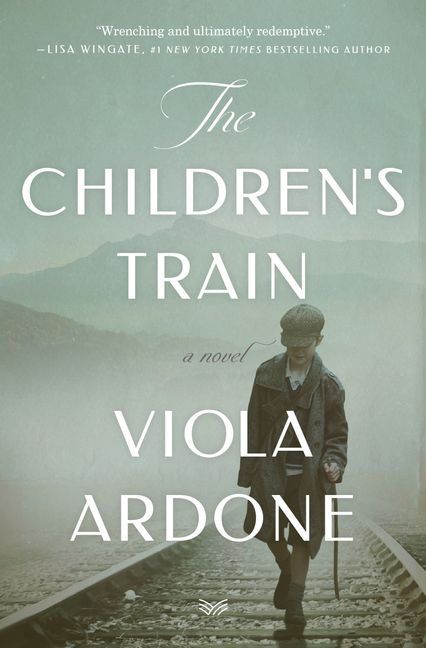

THE CHILDREN’S TRAIN

Viola Ardone

HarperCollins

REVIEWED BY PETER STUPPLES

In 1946, the Italian publisher Gaetano Macchiaroli funded and organised sending a trainload of young children from war-torn Naples to cities in the richer north of the country, where there was more food and the trauma of war had been less severe. The children spent six months billeted with private families, attended school and received an allowance of new clothes.

Communist Party cadres were responsible for the hands-on organisation both in Naples and the Northern towns: throughout Viola Ardone’s novel solidarity and dignity are regarded as virtues to be nurtured and honoured.

Amerigo is a train-child. We live through the details of the preparations and the journey North, the feelings of both excitement and apprehension, even fear amongst his close friends. For him the change of circumstances is positive, opening up doors through education that might never have come his way in Naples. The eventual return home, however, is the very opposite. He is to be sent to work as a cobbler’s apprentice and all the opportunities opened up to him are now tragically closed. But Amerigo is a spirited child and runs away, back to Modena, vowing never to return.

The final section of the novel are set in 1994, when Amerigo, now in his mid-50s, returns to Naples, for the first time since he ran away. It is a brilliantly handled first-person narrative, confirming the poetic structure of the novel, the motifs (shoes, trains), repeated phrases, character developments and inter-relationships, all perfectly balanced. Above all, the psychological pain of the past - ‘‘I’d consumed so much rage that I’d forgotten why I was angry’’ - is worked through to enable a rebalancing of Amerigo’s own selfhood, a resolution and realisation that his mother’s love was never in doubt.

This is a fairy story. Many novels deal with pain and suffering. Few of them, such is our time, offer hope or positive resolution. It is a relief, at times, to be carried along by a literary feat that manages to convey the pain, but also a plausible way of achieving a happy enough ending that leaves the reader feeling buoyed up rather than wrung out.

Peter Stupples, now living in Wellington, used to teach at the University of Otago