New Zealand screenwriter Michael Bennett has turned to a life of crime and is loving every moment.

It is not the balaclava-wearing, ram-raiding type of crime, but an imaginary world where he gets to tell the stories he is passionate about.

And it only started about six years ago when he was introduced to the case of Teina Pora, then still in prison for the 1992 rape and murder of Susan Burdett.

"Since Teina Pora, my life is almost completely crime now, and it’s really enjoyable — it’s what I chose in my reading and watching in any case."

It was through Pora that Bennett started writing prose rather than the screen scripts — comedy, short films, feature films, television — he has become known for over the decades. He has written episodes of Mercy Peak, Mataku, Cover Story, Outrageous Fortune and more recently gang drama Vegas and detective show The Gone, and has been involved with feature films such as Matariki, Jubilee and short films Cow, Kerosene Creek, Night Shift and Ross and Beth.

Bennett (Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Whakaue) was heavily involved in the fight to have Pora’s wrongful conviction for Burdett’s murder overturned — he became a trusted friend of Pora, was on his prison phone list and sat in on the Privy Council case in the United Kingdom texting Pora developments as they happened.

He wrote, directed and co-produced documentary The Confessions of Prisoner ‘T’ which aired two years before the Privy Council quashed Pora’s convictions and then TV film, In Dark Places, based on Pora’s story. He received the best director award at the 2019 NZ Television Awards for that work.

Being so close to the story, Bennett got to know all the players very deeply, and wanted to tell Pora’s story — which he believes epitomises how the justice system fails Māori — but felt the film and documentary genres had their limitations.

"It was out of necessity I suppose. I really wanted to go more deeply both into social aspects of it and the legal, but also the Teina I knew, and to give the reader a look behind the newspaper headlines and get to know this guy for the kind and extraordinary human being I knew him to be."

So a book seemed the only way. Bennett wrote In Dark Places: The confessions of Teina Pora and an ex-cop’s fight for justice which went on to win the 2017 Ngaio Marsh award for best non-fiction.

"I found I loved it."

He found the difference between screenwriting and writing a book is that people read a writer’s words and have a more intimate connection with the writer.

"When you’re a screenwriter, your words disappear, they’re like a dissolving suture, they disappear into nothingness.

"It gave me a real kick because I care about how a sentence goes together, where the comma is, if it is a comma or a semicolon.

"When you write a book, people get to see those choices you make and the way you put together a sentence becomes really important."

Bennett remembers his first screenwriting course, where a speaker told them their job was to tell a story through images.

"When I moved to prose I didn’t really change the way I did it. I think people respond to it because of that.

"I try and make every moment come alive for the reader visually and to take the reader and put them into every scene, to feel like they are in the room, hearing the noises and smelling the smells of the room."

That was a powerful driver for him when telling Teina’s story.

"I wanted to take the reader and put them in the room at that horrible moment which started it all, when a woman was murdered, to convey the awfulness of what happened and also take them into Teina’s prison cell, a room that is smaller than a storage unit, to be in a windowless room for 21 years and know what that feels like — and evoke really strong images in the reader’s mind."

Bennett, who gets up at 5am and is at his standing desk by 7am, describes his process as being very much like having a movie screen going through his head, with the characters moving around within their environment arguing, kissing or talking.

"My job as a writer is to watch what is going on, on the screen, and try to keep up on the keyboard, and it’s very much the same with prose."

So it seemed obvious to write a fiction work next.

"It’s been a natural progression for me, not because I’m devious, because it’s always been incredibly fascinating to me the putting together the puzzle of crime stories but also questions about criminal justice."

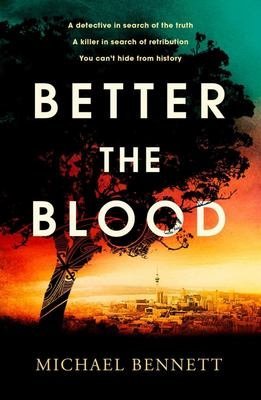

Better The Blood follows Māori police detective Hanna Westerman as she hunts a serial killer in Auckland, uncovering a link to a brutal historical crime that leads back generations to the colonisation of New Zealand.

"The journey through the book is both that journey to find a killer and stop them — a crime genre premise that is driving the book ... but the closer Hanna gets to stopping them finally, the more she is becoming aware actually — while the killer’s solutions are wrong and abhorrent — what they’re talking about makes her reflect on her role in the justice system that hasn’t done well by Māori.

"Those raw scars haven’t been put right and lands haven’t been returned and Māori aren’t being strung up by the neck any more, but we’re still at the bottom of every socioeconomic indices."

Bennett does not shy away from difficult subjects even though it is a fiction work, finding that his experience with Pora has a "direct" impact on his writing even now.

"There’s still issues 200 years after colonisation, so maybe we should be doing something about it, but the answer I don’t believe is violence."

There is also a link to his family history. His father was a World War 2 Spitfire pilot, one of seven brothers who went away to war and they all came home.

"From my dad I got this sense of social justice of fighting the fights worth fighting."

His mother, a writer, met his father while researching her thesis on Bennett’s grandfather, Frederick Augustuce Bennett, the first Māori Bishop of Aotearoa.

"She was a terrific writer.

"Dad was just home from the war and Mum was travelling around the country with Frederick Augustuce, so they met."

Bennett, the youngest child, remembers spending a lot of time with his mother, who gave him a "passion for words" and knowledge of the power of storytelling — "what words can do and how words can change the world".

He can remember doing the "nerdiest" things as a young child. Their favourite game was to get a dictionary each and to test each other on a page of the dictionary to find out who knew the most words.

"It got me strongly interested in writing from an early age."

Growing up in a small town just out of Nelson, the options for those interested in writing were teaching, the law or journalism. So he did a few short courses as a teenager in journalism (including one with TV3 journalist Mike McRoberts).

"I guess I figured out maybe for me, while I admire the hell out of what journalists do, maybe being corralled in by the facts might be a little difficult for me."

Eventually, he found his way to drama storytelling and along the way did a psychology degree, as he was always interested in the human mind.

Still unsure what type of writing suited, he came across a course on screenwriting.

"It was one of those moments of ‘oh, OK’ — you can use creativity and your ability to write to really explore how human beings tick, and make stories that delve deep into the human mind and why we do the extraordinary things we do but also the dark, awful things we do.

"I guess I always felt like a writer, I just didn’t know what kind of writing I’d do."

Now having written for about 25 years — he started out in comedy with his first paying job the 1993 debut season of sketch comedy show Skitz — he has found his inclination that he was not suited to journalism was right.

"The good thing about writing a novel, about fiction, is that you can explore the real truths, the social realities, but can do it in a fictional way which to me is a very powerful thing."

What Bennett wants to do is give readers a powerful engaging interesting story that keeps them turning the pages until the very last one, but at the same time there is a "trojan horse of bigger things and bigger issues snuck in underneath the page turning story".

"You become a writer because you have something burning inside you that you want to say or talk about, and I think if you are not unpeeling yourself to the reader, opening up the things that you celebrate about the world around you, the things you love about humanity but also the things still need fixing — that is really important.’

"If you are not exploring things with deeper reverberations then it is just entertainment. That’s fine, but most writers I know want to be entertaining but also have other stuff to talk about underneath that."

Despite that, he also believes it is important to leave the reader at the end of the book with a sense of hope and humanity — "that ultimately the good things about humanity outweigh the bad things about humanity".

His ability to incorporate the visual in Better the Blood has resulted in him now translating the story into six one-hour episodes for television.

"It’s extremely exciting."

He is also working on a second season of The Gone with an Irish writer and has a feature film in the works which for a change is not about crime.

It is a true story about a friend of his, a young transgender dancer who went to the Cook Islands, fell in love with Cook Island dancing and won dancer of the year.

"It’s sort of Billy Elliot in the South Pacific with beautiful Cook Island dancing, a real feel good story with no crime in it, which is really nice."

TO SEE

Michael Bennett, November 12, 11.30am to 12.30pm, Te Atamira, Queenstown Writers Festival, November 11 & 12