A review of our climate commitments makes it obvious we need to lift our game, Tom McKinlay writes.

Even from a distance, Andrew Sutherland was struck by the hulking mass of the optimistically named Majestic Princess.

But by the time it had almost closed the distance to his small flotilla of two paddleboards - and a protest sign - its nominal majesty was overwhelming, its vast terraced cliffs of cabins stretching up, and up, towards the smokestack.

He was also struck by the fact that, according to his count, only five people had bothered to come out on their cabin balconies to take in the views.

‘‘This is surely what you’re doing this for - just to soak up the views of these amazing places, you know, particularly the slow mo of the harbour.’’

Sutherland was out bobbing on Otago Harbour on the March morning in question as part of Climate Liberation Aotearoa, a protest group trying to bring a focus to the carbon emissions of the cruise-ship industry.

Among the issues is that the megatonnes of carbon pollution from cruise ships’ funnels are currently going largely unaccounted for.

‘‘Because we have just cooked the books, essentially,’’ Sutherland says. ‘‘Cooking the books and the planet.’’

However, the free pass handed to the Majestic Princess and her fellow royals might be coming to an end.

He Pou a Rangi, the Climate Change Commission, is currently consulting on whether emissions from international shipping - and aviation - should be included in our country’s carbon cutting goals out to 2050. And, if so, how.

There’s no great mystery as to why these travel emissions have been missing from the carbon accounts until now. Just like agriculture’s absence from our own emissions trading scheme, aviation and maritime emissions were excluded from the Kyoto Protocol back in day because it was deemed too hard.

That particular too-hard basket was shuffled sideways to the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) - which took their time. But they have now set targets to reduce international shipping and aviation emissions to net zero globally by 2050 - even if they haven’t entirely sorted the how of it yet.

It is certainly not going to happen without individual countries taking action and the likes of the European Union, United Kingdom and United States are moving on it.

So, He Pou a Rangi, the commission, is suggesting we do too.

It’s not like carbon emissions haven’t been on industry minds hereabouts. Aurora Energy has been looking into providing an electricity supply to ships when they are in Port Chalmers. The ships could then turn off their fossil fuel engines, cutting both air and noise pollution for a time. And the port is Toitū carbon reduction certified, at least for the operations of the port itself.

However, the work the commission is doing is potentially much more all encompassing.

And still not easy, Kyoto got that right.

As the commission sets out, international shipping and aviation emissions cover all travel and freight going from here to anywhere else, and back again - as well as emissions from travel within Aotearoa New Zealand when an international vessel stops at more than one domestic port.

And it’s not as simple as deciding whether to count these things or not as part of our 2050 journey. If we plump for yes, then how do we calculate it? Based on the refuelling done here? The fuel use to or from the next port? Just the fuel used within our exclusive economic zone?

Assoc Prof Inga Smith, co-director of He Kaupapa Hononga, the climate change research network of Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka, the University of Otago, knows something of these difficulties. She, an Antarctic sea ice physics researcher by trade, set out to crunch some of the numbers more than a decade ago, with fellow physics department staffer, Prof Craig Rodger, a space weather expert, because no-one else was.

Among their findings was that cruise ship passengers were generating about three to four times as much carbon per kilometre travelled as plane passengers.

‘‘They’re very inefficient and very polluting in terms of carbon emissions,’’ she says.

Cruise ships aren’t really transport, Assoc Prof Smith points out. Rather they are floating, moving hotels and mini-cities that continuously burn fossil fuels to keep the lights on, the water flowing, and the temperatures comfortable - and provide luxuries such as on board restaurants, bars, swimming pools, and entertainment venues.

“If you were just looking at carbon emissions per passenger kilometre and deciding which international shipping and aviation activities needed to be stopped completely, then cruise ships would be high on the list.”

Of course, this isn’t just about cruise ships though. Much of our trade goes on by sea.

For that reason, she says we’re particularly exposed.

‘‘It’s definitely a risk for us not to be on top of this issue in terms of knowing what’s going on, knowing what our emissions are, and thinking about that.’’

We’re much better to be on the crest of the wave of change, she says, than wallowing in the backwash.

‘‘If we don’t set standards for emissions, then we could become a dumping ground for less efficient ships and less efficient planes servicing our routes.’’

A research project Assoc Prof Smith led a couple of years ago, with researcher Anna Tarr, highlighted some of the risk there. They identified a 60% rise in carbon dioxide emissions from passenger travel to and from New Zealand between 2007 and 2017 - which was ahead of the rise in passenger numbers.

Among the causes for the apparent decrease in efficiency, across 21 airlines, appeared to be operational factors such as seating density.

As long as the sector sat outside carbon cutting regimes, it faced no incentive to look at that.

However, the scale of the pollution from these sectors also flags the potential for improvement.

In its review, the commission estimates emissions from the fuel taken on board here by ships and planes in 2019 were close to 5 MtCO2e. That is equal to 9% of the country’s total net greenhouse gases - for which we don’t yet account - and in the 10 years to 2019, they jumped 51%.

Globally, if action is not taken, it’s estimated that the two sectors could consume 20% of the world’s remaining carbon budget.

Curiously, aviation has had a particular hurdle to overcome to tackle its emissions, as an international agreement struck in 1944 made jet fuel used for international flights exempt from tax - such as a carbon tax, for example.

The ICAO has now established the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for Aviation (Corsia), which will make it mandatory for most airline operators to offset their CO2 emissions - above 85% of 2019 emissions - from 2027.

Assoc Prof Smith warns against waiting for technology to solve the problem. Electric planes cannot currently fly internationally and the prospect of ‘‘green’’ aviation fuels was this week described as ‘‘magical thinking’’ by one commentator.

Locally, it is, again, not as if no action is being taken by those involved in the sector.

Dunedin Airport, for example, while not currently involved in international travel, does measure the carbon footprint of the airport’s own operations, and has a goal for that to be net zero by 2030. The biggest part of the emissions it does currently measure is the dairy farming on its land.

It does have plans to start reporting aircraft emissions, but just for landings and takeoffs.

Interestingly, the Dunedin City Council’s work on its own 2030 net zero targets avoided all the too-hard-basket complications of the international goal setters by tackling the problem head on.

International shipping and aviation emissions are already included in the DCC zero carbon plan.

‘‘The method used for both the aviation and marine emissions were to split the emissions of port of origin and port of destination,’’ kaitātari matua/senior policy analyst, zero carbon Rory McLean says.

So, for example, for a flight going from Dunedin to Auckland, half of the emissions of that flight would be attributed to Dunedin.

It does mean that as things stand, with international flights currently leaving from other ports, Dunedin residents’ overseas travel will show up in the inventory of the international airport concerned - say, Christchurch, for example.

In terms of marine emissions, in the DCC calculations, Port Otago tends to take a larger share of the emissions than other stops because it is often the first or last port a vessel visits in the country, so Dunedin takes a half share of the international leg of the journey.

To date, emissions from cruise vessels have not been included in the Dunedin city inventory, or the zero carbon plan, because of difficulty getting good data. However, the council is looking to calculate emissions from cruise vessels in the coming months.

Christchurch has just begun including cruise ships’ emissions in its greenhouse gas inventory and estimates they are equivalent to 2% of the city’s total gross emissions, and 4% of transport emissions. Cruise ship emissions could be up to 55% of its marine transport emissions.

It all underlines the importance of the commission’s work towards identifying the best way to include and account for these emissions nationally.

Of the four options it presents, Assoc Prof Smith prefers the third, which seeks gross (i.e., real) reductions separately for international shipping and international aviation. The commission says that an approach that would be consistent with approaches taken globally is the first that they list, which is to simply include marine and aviation emissions in the country’s existing net zero 2050 target. That and their fourth option would allow offsetting.

The cost implications of accounting for carbon is often where commitment starts to get shaky, but given shipping is usually a relatively small proportion of the cost of a product, the commission says the impact on consumers might be in the range of 0-0.7%.

And as far as aviation goes, the Mission Possible Partnership’s modelling found that fully decarbonising aviation could increase fuel costs 90-190% but improved efficiency and technology improvements could mean the overall change in average costs for aviation was between a 5% increase and a 5% decrease.

At the same time as it is seeking feedback on its review of that issue, the commission is also consulting on a review of our 2050 emissions reduction target. It has to do that under the country’s Climate Change Response Act 2002.

But if its statutory responsibilities hadn’t prompted it, there would have been plenty of other reasons to have another gander at the target. As it notes in its 2050 review document, ‘‘the worsening effects of climate change are being felt around the world ... 2023 was the warmest year on Earth since records began in 1850, driven in large part by human activity. To avoid the worst effects of climate change, urgent and sustained action is needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.’’

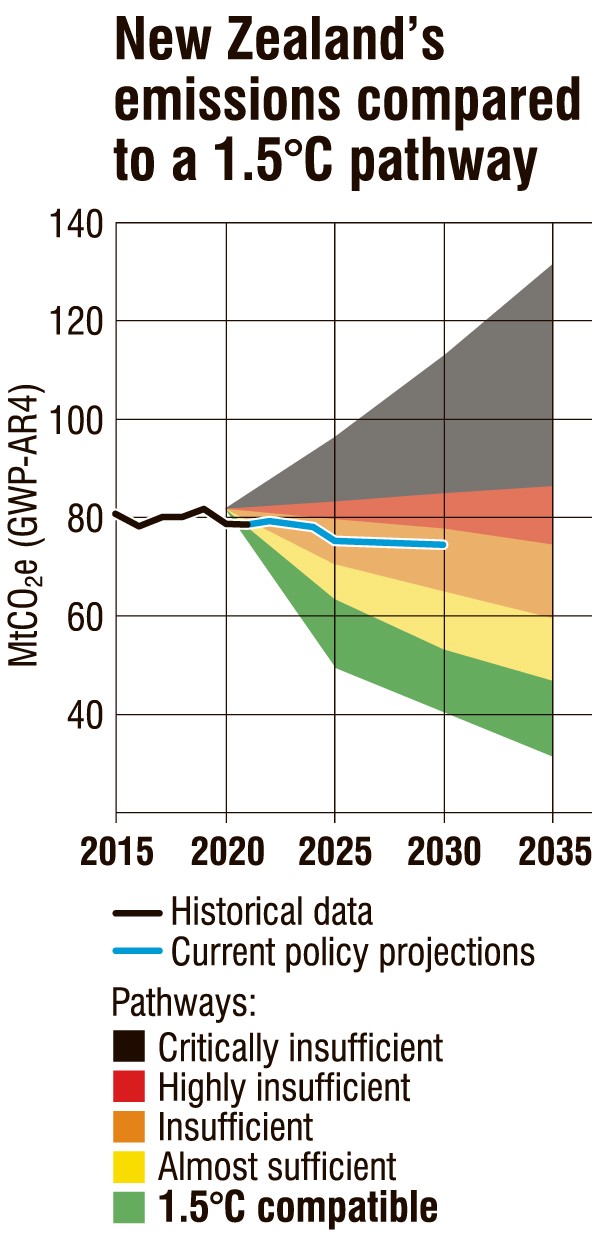

And we’re not yet doing our bit.

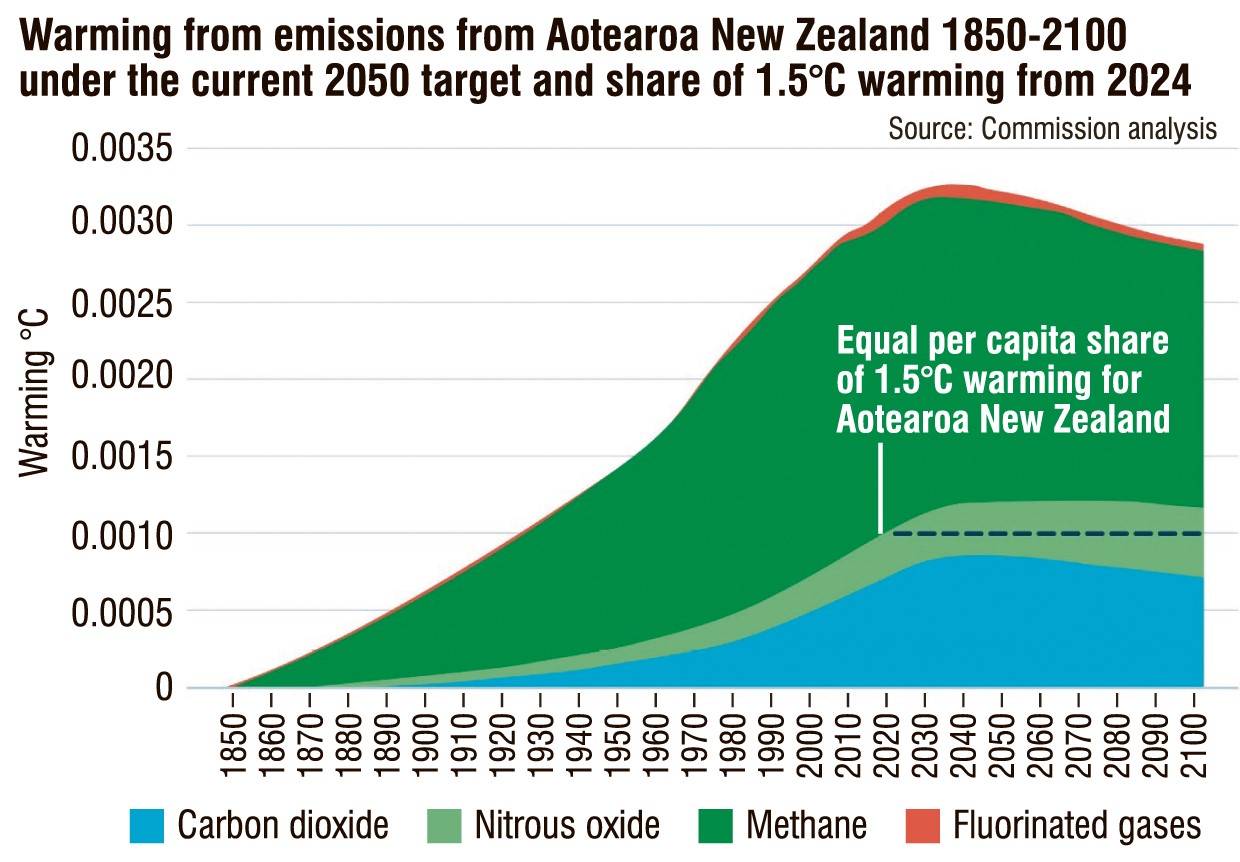

If everyone in the world contributed the same level of warming per capita as Aotearoa New Zealand, total warming would peak at about 5°C and decline to around 4.3°C by 2100, the commission says.

Its conclusion, our current 2050 target is not compatible with bearing our share of the international burden.

The rolling impacts of heat, flood and fires means many now regard the DCC’s 2030 target as being a lot closer to the science than any talk of 2050. Given the mercury last year was touching 1.5°C already and the latest estimates are that we have no more than about six or seven years of remaining carbon budget to avoid catastrophic warming, the commission’s talk of the more distant date seems out of step. However, that is the date in its legislation.

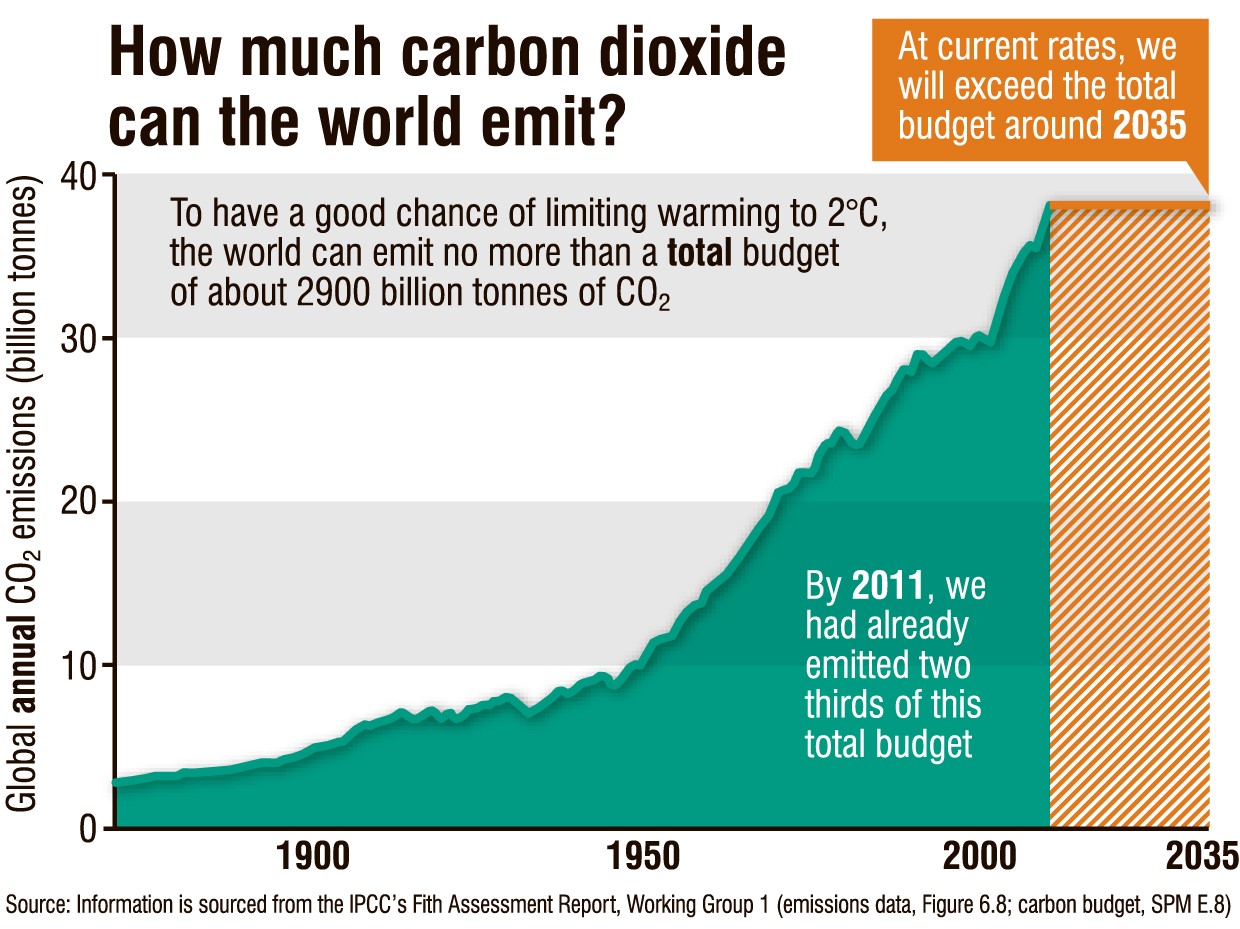

Assoc Prof Smith references a graph she uses in a second-year environmental physics paper, which covers how New Zealand’s Nationally Determined Contribution was consulted on in 2015 by the then National-led government. The graph gets to the nub of the matter.

It shows that in 2015, the science said that if carbon emissions had peaked in 2011 we’d have had until 2035 to reach net zero.

‘‘But of course, carbon emissions were not held at 2011 levels.’’

So we don’t have that long.

‘‘And then we fall off a cliff.’’

In that context, He Pou a Rangi, the commission, is also currently consulting on the fourth emissions budget, as part of its zero carbon planning mandate, for the five-year period between 2036 and 2040. It recommends that we should set the budget for that period at 134 MtCO2e, or 26.8 MtCO2e a year, down from the current 70.3 MtCO2e a year.

Assoc Prof Smith’s sense of it is that we seem to lose sight of the ‘‘why’’ of all these important numbers, the remaining carbon budget, the temperatures, whether 1.5°C or 2°C - and we’re still on a trajectory to exceeding the latter - and then all sorts of political inertia sets in.

‘‘If we’re still on a trajectory to exceeding two degrees, then that’s a significant problem.’’

To put it another way, and a report from the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries - sober-suited accountants - just has, we need to be more realistic in our assessment of climate risks, including, they say, assessing the ‘‘risk of ruin’’, the point past which global society can no longer adapt to climate change.

Among the actuaries’ concerns were tipping points connected to ice melt, which is why many Antarctic scientists are very concerned, including Assoc Prof Smith.

‘‘As a PhD student I’d been to conference and seen significant warming being reported from the Arctic and warming being reported for the Antarctic Peninsula, and was really concerned. Why was no-one doing anything about this? Having worked in those kinds of policy relevant things, I now realise it’s really hard for people to change, even when they want to.’’

A recent poll of scientists conducted by The Guardian newspaper found many now have their heads almost permanently supported by their hands. Despair has become the enemy.

Still, as Assoc Prof Smith notes, the last big assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change made the point that any and all kilograms of CO2 that we can avoid from here on in, will reduce the amount of planetary heating. Will reduce the damage.

The consultation

He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission is consulting on three documents until the end of May.

• Review on whether emissions from international shipping and aviation should be included in the 2050 target

• Review of the 2050 emissions reduction target

• Draft advice on the fourth emissions budget (2036–2040)