On a crisp evening in July, Paige Jansen's clothes gyrate through the air, draped on the bodies of dancers moving in rhythm to the improvised sounds of live cello, double bass and synthesizer. This uniquely appealing show of Jansen's work takes place within the warm belly of Dunedin's George St - the industrial-looking basement retail space, Underground - where lighting illuminates the soft contours of the flowing garments.

Dunedin Dream Brokerage found the venue, the community dancers were led by choreographer Julie Harvie from Movement Art Practice (MAP) and the event was dreamed up and brought to fruition by Jansen.

Jansen is an early career designer/maker who specialises in creating and making slow clothing. Originally from Christchurch, she completed a bachelor of design, in fashion, at Otago Polytechnic, graduating in 2017.

"Since about age 13 I knew that I wanted to study fashion design. But it's so changed from what my perception was then to what I am doing now.''

Through her business, Paige Jansen Store, Jansen designs and sells clothing in natural fabrics that she hand-makes using techniques such as French seams that make a garment "as beautiful on the inside as it is on the outside,'' she says.

She obtains her natural fabrics, of predominantly linen, cotton and silk, from New Zealand suppliers or as vintage fabrics from secondhand shops. She then colours them with natural dyes, cuts her patterns and sews them with cotton thread. Sustainability throughout the design process is also observed. Instead of buying new fabric to test or mock-up her creations, she uses discarded fabrics that she collects from second-hand shops.

It promotes clothes that are good - well made from quality materials that can be worn for longer; clean - their impact on the environment is minimised; and fair - workers rights are respected and they are paid fairly. The movement sits in juxtaposition to the fast fashion industry, in which clothes are often poor in quality, their manufacture pollutes the environment and workers are exploited.

Fast fashion is on the rise. Globally, the volume of clothing produced by manufacturers has doubled in the past 15 years, according to the World Economic Forum, and the duration that clothes are worn before being discarded has fallen by 40%.

In response, movements globally and locally are challenging the industry to shift towards a more circular model of production, in which designers endeavour to follow the trail of production, keep materials in circulation for as long as possible and produce no waste. New Zealand Eco Fashion Week Ltd and Stitch Kitchen, in Dunedin, are New Zealand examples of initiatives that support the circular model.

Jansen's decision to pursue a career in slow clothing evolved during her degree.

"The sustainability sector within my degree was huge. Every single paper we did, whether it was just writing or practical, we had to think about how we could practise in a sustainable way.''

Slow-clothing designers need wearers to play their part too.

Before handing over your credit card, slow-clothing designer and maker Jessica Matthews recommends the mental habit of asking yourself, "Will I wear this at least 30 times?''. Matthews, of Wellington, also works with natural fibres as much as possible under the name Summers the Label. She has picked up on the #30Wears hashtag challenge originally created by fashion designer Livia Firth. "It's an easy thing to visualise in your head,'' Matthews says.

Wearing something 30 times might not sound like many but a 2017 study in Denmark, involving more than 4000 European and US participants from a variety of backgrounds, found that each person introduced an average of 5.9 pieces of clothing into their wardrobe over a three-month period.

Part of the problem is the vast quantity of low-quality low-cost clothing available.

"You buy a T-shirt for $7 and you expect it to not last for 30 wears, let alone 30 washes,'' Matthews says.

In terms of her own garments, Matthews has faith in the quality of the fabrics she uses, even delicate silk.

"They stay fresher, retain their integrity better [than synthetics].''

But how can a manufacturer making a few pieces of handmade clothing compete with that $7 T-shirt?

Fiona Clements, also a graduate of the polytechnic's design school, believes equity is a huge issue that must be addressed if sustainable fashion is going to succeed.

"Only the very rich can afford to buy quality long-lasting garments, or you have to save for such a long period of time and in that time you still have to clothe yourself.''

Clements' own work focuses on the waste minimisation element of the circular clothing process. She used to make garments from offcuts discarded by producers at the assembly stage. At Vogel St social enterprise Stitch Kitchen, she works with Fiona Jenkin to bring people together and upskills people interested in crafting, upcycling and repairing clothes.

Part of that is a focus on natural fibres.

"I think we have to start getting back to natural products so that they are circular in their creation and use - so that when they do end up in landfill they are not creating so much of an issue.''

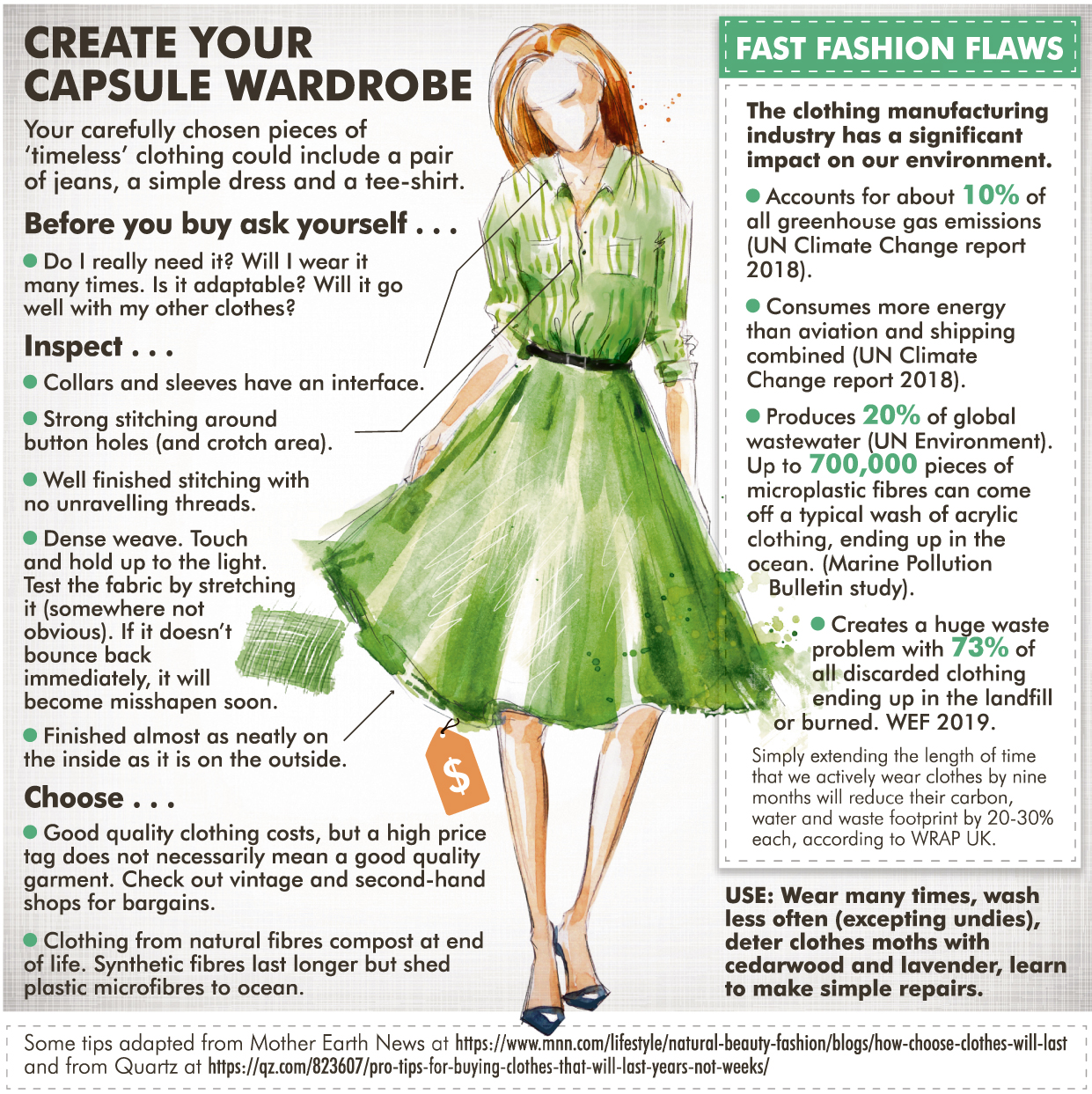

At the personal level, Clements recommends getting back to the capsule wardrobe, made up of a small number of clothes items that complement one another and can be worn together in different ways.

"It's `How can you have something that you can wear in 10 different ways, that can be altered, that can be added to with a little bit of creativity every now and again?'

It requires a little insight.

"It's knowing yourself well enough to know what really does suit you. And bucking the trends of you've got to have what's hot right now.''

Leading figures embracing the simplicity of a capsule wardrobe include Mark Zuckerberg, Barak Obama and art director Matilda Kahl, who wear the same, or at least similar-looking, clothes to work each day.

"We have to get past [the idea] that you have to look fresh and new every day,'' Clements says. "You can still achieve that with a bit of innovation and creativity,'' she adds.

Rehabilitating the fashion industry is an ongoing learning process, Jansen says.

"Every year it changes and I learn how I can better my practice. It's a process of constant development that goes beyond just making clothing.''

Ultimately, slow-clothing designers want people to wear their clothes - and then to wear them out.

"They are pieces I want people to have in their life for, like, 20 years. I want you to wear it until it's got holes in all the shoulders, and then patch them up and keep wearing it,'' Jansen enthuses.