For 15 hours he swum strongly. Enveloped from head to foot in a black swimming suit covered with grease, he laughed and joked with his wife and friends on the tug, and chaffed his two little stepsons. His strength may be gathered from the fact that he was only making one stroke less per minute than when he started. At 10am he was only two miles from Dover. The night had passed with smooth seas and favouring tides. Crowds on the Dover beach joyfully watched his apparent triumphant progress. Suddenly the sea grew choppy and the wind turned. The swimmer stripped off his bathing suit and swam doggedly on. His strength was not yet undermined, and he made for the west entrance of the harbour. Then the tide turned. The swimmer began rapidly to drift along the coast towards St Margaret’s Bay. He was carried past Dover, and all hope of entering the harbour was lost. The objective was now changed to the rocks near St Margaret's Bay, and the swimmer battled doggedly against the fast-running water. Inch by inch he drew nearer to the shore, but all the while he was being edged along the coast.

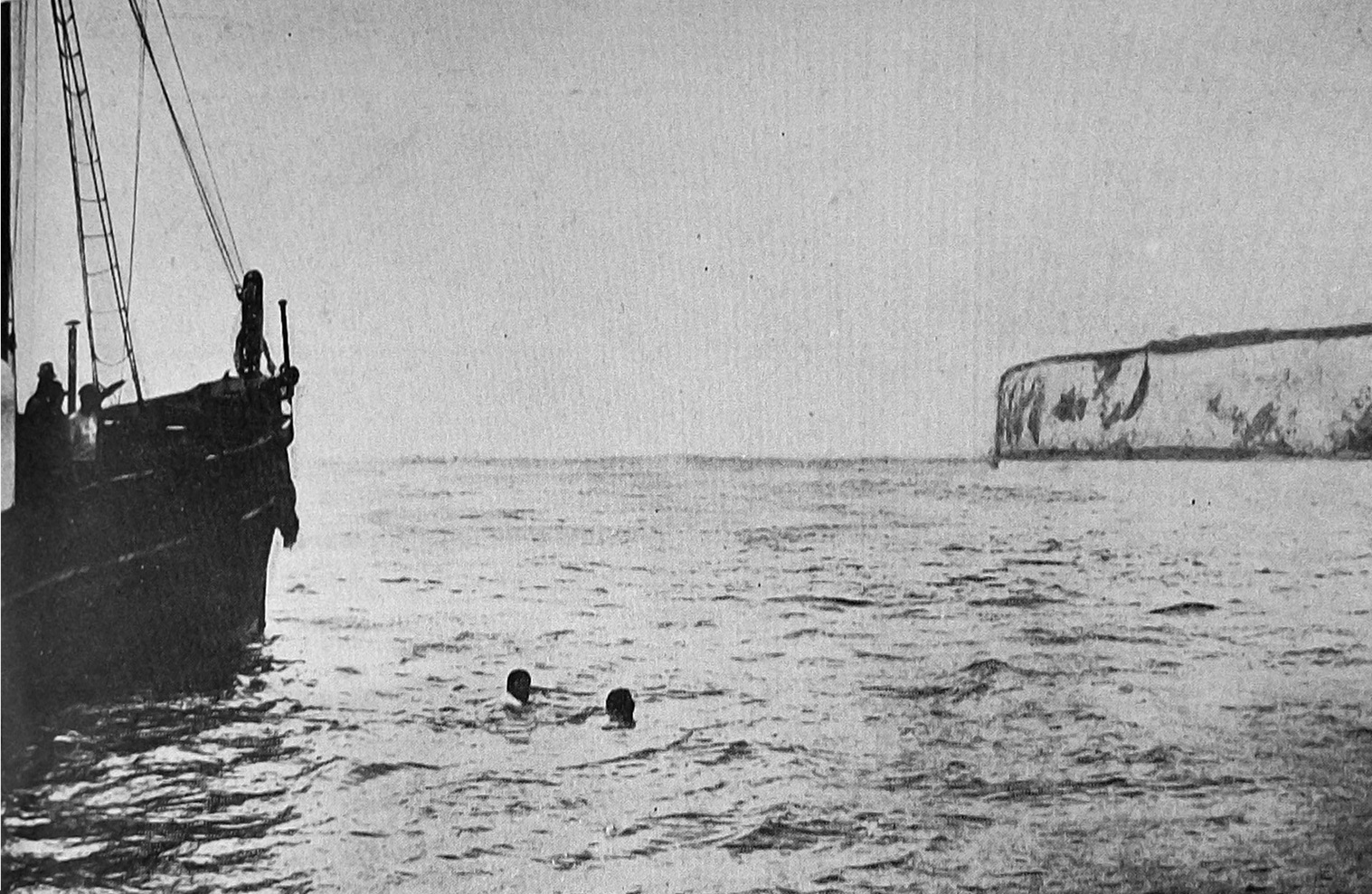

A mile from the coast he had to be given brandy. His steel strength had at last begun to wane. "Give in," urged his wife. She could see that her husband had suddenly reached the end of his strength. He shook his head. The nerves of those on board the tug were at snapping point. Would he prove strong enough to reach the cliffs? They were then only 700 yards off. A second dose of brandy was administered. The swimmer’s face was expressionless, his eyes were bloodshot and blurred. Once he began to swim in the wrong direction and had to be turned again to his track by shouts from the crowd.

Five hundred yards from England and victory the end came, for every ounce of vitality had gone and the swimmer could merely stroke the water with his hands. The spirit to go on was still uppermost, but the human body could no longer answer. Mrs Freyberg acted with reasoned judgment when she called on him to give in. It was galling for her to have to bring on herself her husband’s defeat, but it was now clear that it was dangerous for the swimmer to struggle on.

As Colonel Freyberg was lifted over the side, his wife, who throughout the swim had been unfailing in her encouragement, gave him an affectionate kiss. He was taken from the water at 1.05pm, after swimming 16 hours, and was brought to Dover, where he had a great reception. — by ODT London correspondent — ODT, 18.9.1925

Compiled by Peter Dowden