It was the disaster that could not happen in a modern mine, they said. But it did.

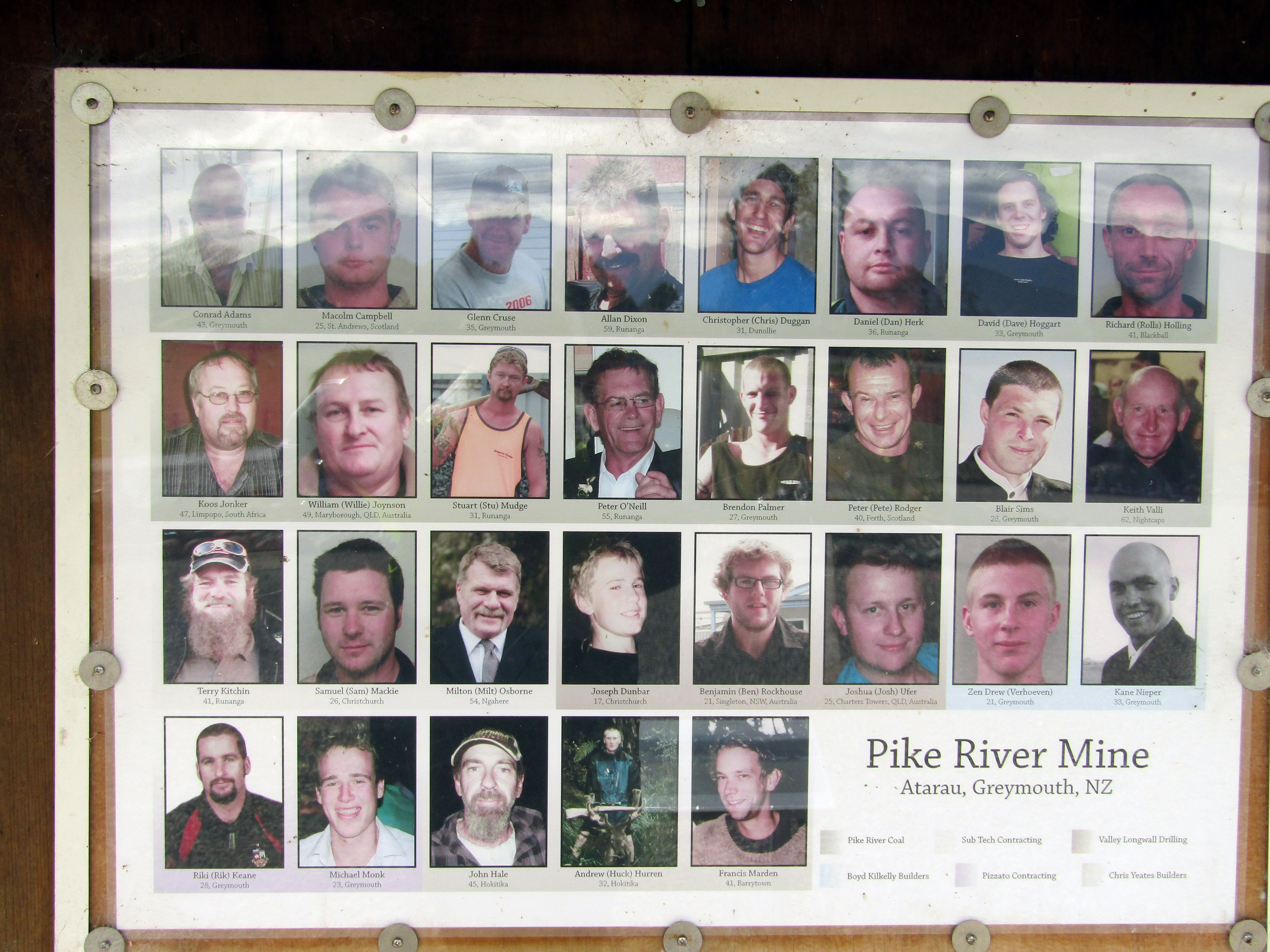

In a heartbeat, at 3.44pm on November 19, 2010, right at the end of the Friday afternoon shift and with thoughts turning to the weekend, a huge explosion ripped through the mine, killing 29 men.

It took 49 minutes for rescuers to be called.

As night fell, they lowered listening devices underground. Fleets of fire trucks stood idle as flames erupted out of the ventilation fan like Dante’s inferno.

The top cop from Christchurch arrived to take charge of the situation, and googled "mines rescue" on the drive to the Coast. He then went back to retrieve body bags.

Pike River Coal Company chief executive Peter Whittall — the former mine manager who designed and oversaw every aspect of the mine development — faced mobs of media and assured them that the men were alive, down below, sucking on an airline.

Until the mine blew again a couple of days later.

Families’ hopes were cruelly shattered when officials addressed them honestly for the first time in an emotional meeting at the Civic Centre in Greymouth and told them there was no hope of survival.

With hope also went the myth of a modern, safe mine.

Under the full glare of a Royal Commission of Inquiry, the Department of Labour’s full failings were shown, managers exposed.

Families clung to pictures of loved ones, trying to see a way ahead.

Most charges were dropped and the mine was to be sealed — until Anna Osborne stepped up and occupied the mine road, preventing Solid Energy contractors from completing the 30m-long concrete seal.

Then state-owned Solid Energy went under, and out went the National government, replaced by a new coalition government which gave birth to the Pike River Recovery Agency.

Now, even the then unborn children of the Pike River mine victims are at least 10 years old.

The government regulator has been fully overhauled.

The re-entry may prove once and for all if faulty and inadequate electrical equipment provided the spark that ignited the gas inside the mine that fateful day. These are answers they have been waiting a decade for.

The families have chosen their own paths through the grief. But 29 men had no choice, when their journey ended 2.3km underground on a sunny spring afternoon.

THE RECOVERY

The Pike River Coal mine. Its concrete-faced portal dripping with fern and studded with trees, the cut eastern faces of the Paparoa Range escarpment soaring above.

It is a remote and beautiful place for a tomb — and the most expensive and challenging forensic examination in the country.

"Pike had the potential to be one of the best operating mines in New Zealand," recovery agency chief operating officer Dinghy Pattinson says.

"But it will be remembered for all the wrong reasons."

Last May, 29 yellow balloons were released, and the surrounding hills told the names of those killed, as Mr Pattinson led the recovery team into the mine.

It also marked the final hunt for forensic evidence. And a story which started with empty promises and ended in the loss of 29 men.

Progress up the drift, between the portal to the workings, started slowly. Every move planned, every eventuality examined.

An exemption needed to pass the 170m barrier came through last October, and the barrier was breached in January.

Rotary drilling for the roof support work was being replaced with percussive when Covid-19 hit. The team was 475m up the tunnel at the time; weeks were lost.

"After lockdown we had to work out how we could catch up. The Government is not going to just give us more money — we know that," Mr Pattinson said.

"Pit Bottom in Stone", where the lattice of roadways hold Pike’s mining infrastructure, 1880m down the drift from the portal, was reached on September 16.

Re-entry miners are carefully stepping towards the Roscil plug and the rockfall, beyond which lies the labyrinth of 4.3km of workings through the gassy Brunner coal seam — and 29 bodies.

The plan, provided unexpected unknowns do not mar progress, is to build a ventilation control device on the portal side of the plug, tunnel the plug and "recover" the drift to the rockfall using breathing apparatus.

Mr Pattinson takes a cautious approach.

"All eyes are on us. Lots of people have said Pike should not be re-entered and can’t be re-entered safely."

Millions of cubic metres of nitrogen gas have been pumped into the mine to create an inert barrier between methane and the fresh air supply.

Encased in air, the recovery teams then forensically examine 20m sections before pulling their air supply up another 20m and beginning the process again.

Everything found is handed to the on-site New Zealand Police forensics team.

"The rockfall is the end of the project — and no-one has had eyes on it. It’s all about forensics."

Mr Pattinson said the re-entry was a learning curve for the industry, about the importance of not taking shortcuts, and health and safety.

"The New Zealand workplace has to learn to say when enough is enough, and stop to get better advice. Until they get that thinking, we will still have workplace accidents and fatalities.

"If we ever forget what happened here, it will happen again.

"We can never forget."

THE MOTHER

Jo Ufer thinks of her son, Joshua, every day.

The Australian drilling supervisor came from a family of Townsville miners. He crossed the Tasman after the company he worked for in Queensland, Valley Longwall, won a contract at Pike River, on New Zealand’s scenic West Coast.

He was 25 when the mine exploded six months later.

From her home in Singleton, on the banks of the Hunter River in New South Wales, Ms Ufer said Joshua would never be forgotten.

She was learning to live with his death.

"I do not like the term, ‘moving on’, because it’s such a big statement. But we do learn to live with it."

But the loss of his life not lived with his Greymouth partner, Rachelle Weaver, and the daughter he never got to meet, Erika Ufer, was painful.

"I see fathers with their children and think Josh never got the chance to see his daughter — there are so many family things he has not been around for."

Ms Ufer said she felt far away from events most of the time.

And the years of political battling over the re-entry left her doubting it would go ahead.

"But I went over there and sat in, when they were going through the risk assessments for the re-entry, it became clearer in my mind.

"It has all happened in the last 12 months. It’s amazing and I take my hat off to the agency."

She walked the mine’s drift to the 170m seal with other Pike River families last October.

"It was a very emotional time and the closest I had been to Josh in a long time. It made it very real. But every time I go over I get the feeling I haven’t been able to bring him home.

"I’m reconciled that I may never be able to bring him home.

"Some people want to get on with their lives but, working in the industry, it’s important to me not to forget.

"I feel the loss of Josh every day — you can not get over that."

Friends and family on both sides of the Tasman had made it a little bit easier, she said.

However, 10 years after the 29 men died, no-one had been held responsible, and the company’s officials had moved to new jobs and lives with no implications at all.

"I know Josh would have wanted me to live my life and be as happy as I can. I live my life for two people now."

Jo Ufer herself works in the Australian mining industry and has been recognised for her safety awareness focus.

In an open letter to the industry in 2013, after four mining deaths in Australia, she said it appeared the lessons of the past were not being taken on board.

"My son died in an underground coalmine disaster, but the environment doesn’t really matter. Many of us get up, go to work, do our day’s toil and go home with little thought to the enormity of that risk.

"I myself did not for one minute ever think that there was the chance that my son would go to work one day and that would be it. I would never speak to him, or see him or hold him ever again."

THE MINISTER

Andrew Little keeps Pike’s miners close. A photo of the 29 men on his office wall is his constant witness.

"They remind me every day of my determination to bring some resolution for their families."

He cannot forget them. They died on his watch.

When the mine exploded, Mr Little headed the country’s largest union, the Engineering, Printing and Manufacturing Union (EPMU) — now he is the Minister Responsible for Pike River Re-entry.

The union had been "aware of concerns and issues among the guys around safety and the feeling of being unsafe" while the Pike River Coal Company was operating, he said.

The miners were encouraged to fill out near-miss reports, he said.

"We later found bundles of them in cupboards."

Miners had raised issues, "but many were reluctant to put their heads above the parapet".

However, immediately after the first explosion, he told media there was "nothing unusual about Pike River, or this mine, we have been particularly concerned about".

Today, he says the workplace accident should not have happened and was due to failures at corporate level.

The Department of Labour’s oversight was "woefully inadequate" and inspectors were not getting to site, he said.

In defence of the re-entry tapping its $51million financial ceiling, he said no-one knew what would be found until the project started.

"It is a huge job and excellent work is being done by Dave Gawn, Dinghy Pattinson and the recovery crew.

"If we can recover the [electrical] gear we can better understand the cause of the initial explosion. That gives us the best explanation for the tragedy.

"If we can recover any remains, it will assist any families and loved ones.

"I think the families would like to know what happened. They would like to see a prosecution. But we have to rely on police to make that judgement. Until now, no-one has been called to account."

At project’s end, he would like to say everything possible had been done in terms of recovering the drift and forensic information.

And that the effort had helped families step closer to closure.

"There comes a time we have to live with this and recognise we have done everything we can — and it is time to move on.

"I think the disaster is a huge disappointment in this day and age. It blew the sense of confidence the West Coast had at the time.

"But the Coast is an amazing place — they look after their own."

THE BATTLER

Cancer and losing Milton, her husband of 18 years, to Pike River’s maw have not stripped Anna Osborne of her spirit.

"I will survive and carry on and live — and get some truth."

Truth, justice, the Family Reference Group, the Pike River Recovery Agency, the police and her two children and 3-year-old granddaughter, Analia, are her world now.

So is the bone marrow cancer she has battled since 2002. Stem cell treatment in October bought a few more years, and the chance to see Analia go to school.

But do not think Mrs Osborne would swap her life for anyone else’s.

"Milt was my life, my rock and my soulmate. I married a man who cared for me and everyone. And everyone loved him.

"My husband lost his voice that day."

Those left behind represented those lost, she said.

"We are their voices — so we have to carry on."

Mrs Osborne, together with Sonya Rockhouse, who lost her son Ben in the explosion, forced their way into the national consciousness when the mine’s later owner, Solid Energy, wanted to seal its portal with a 30m-long plug of concrete in 2016.

"That made me angry. There was no way they were going to put a permanent seal on my husband’s tomb," she said.

They famously occupied the roadway to the mine, complete with a caravan called Priscilla, barbecue, portaloo and kitchen sink — stopping contractors from entering to finish the job.

Joined by the father of Pike miner Dan Herk, Rowdy Durbridge, documentary film-maker Tony Sartorius and advocacy support and adviser Rob Egan, they formed the Family Reference Group, to represent some of the families of Pike miners and spearhead the campaign for the re-entry.

"We could not have done it without the support of so many people," Mrs Osborne said.

The re-entry announcement was the day when she could "lose her angry pants".

"It felt amazing not having to fight.

"I’m hoping the truth will come forward. I believe in my heart the police will get it right. They have a lot to answer for and they are putting all their resources into making this right.

"I believe they will get a prosecution — I have to believe that."

Her walk into the drift with Sonya Rockhouse last October was surreal.

"It was the very track Milt took that day to go to work. At every step I thought, ‘He’s been here’.

"It was cold. It was dark. I felt awful. I could not do it — let alone for 16 hours a day, which was what the company required of them to increase production."

She still sometimes expected her husband to walk through the door.

"He worked in Bolivia for 13 months and sometimes I have to think he is still there working ... some days are so dark and sad and lonely without him."

In her heart of hearts, she was praying the re-entry team would find the driftrunner which entered the mine before the explosion to ferry out men at the end of their shift.

The insult to her husband’s death was that he was not a miner, but a contractor who was asked to start his own business for the mine. He had worked there for five months.

"It was huge for us because we were happy living from week to week. Milt saw it as an opportunity to make some money, fix the hole in the roof and go on the honeymoon we never had."

Comments

Why would miners themselves, managers, contractors do what is reported here?

Pike River enquiry. Volume 2 Part 1:10.54

See Vol 2 part 1:12.27 Bonus Chart

54. The joint investigation revealed many reports of underground workers at Pike bypassing machine-mounted sensors

by various means. One worker admitted he covered a gas sensor with a plastic bag.94 He did that ‘just to save it

tripping and havin’ to wait around for an electrician … and save the boys’ legs’.95 He heard of gas detectors being

covered on other machines including loaders, and he thought every miner knew how to do it.96 Another miner saw

compressed air being blown onto gas sensors to keep the machine cutting, and miners using metal clips to override

machine-mounted sensors.97 He saw machines overridden following gas trips ‘quite a few times illegally’.98 Indeed, ‘it

happened so often’ that he would come on shift and find the previous shift had left the metal clip in place, because

‘everyone – not everyone, but a lot of people did it’.99 He said in his view workers bypassed gas detectors ‘out of

frustration’ because of the poor standard of equipment at Pike River and the need to get the job done.

Why would there be no inspections? There were no Mines Inspectors. This is not a time to be snippy about the dead of the Valley.

To understand the context around the blocking of machine mounted gas sensors you need to know that the company had done many things to persuade the men that the environment underground was far safer than it really was. The SCADA system was reporting that the airflow at the time of the explosion was 154 m/s, in fact the fan curves show that the main fan could only push 118m/s flat out, it never ran at full speed because of major (and fatal) problems with the VVVF drives. The only methane sensor reading bulk air in the mine (two out the three had already failed) was reading exactly half the true level of methane.

The bottom line is that the company built a system that convinced the men that they were in a very safe environment, that there was a huge margin for error in terms of safety. While the blocking of sensors should never be condoned, the companies abject failure to provide even a hint of an adequate gas drainage system and Doug White's decision to "free vent" methane in the mine meant that nuisance trips were always going to be at plague level and that miners under pressure to increase production in a poorly designed and managed mine were going to take shortcuts.