Reece Adamson should know a thing or two about bees. After all, his family has been beekeeping for five generations, first in South Canterbury and latterly in Central Otago.

'There’s no honey to be made from swedes or ryecorn or lucerne, Mr Adamson and his wife, Louise, now run Wildpure Ltd, producing organic thyme and clover honey, near Alexandra, which is mostly exported to Europe.

It all began back in the late 1860s with Scottish-born Andrew Gibson, who farmed near Temuka, and was one of the pioneers of beekeeping in New Zealand.

In 1906, Mr Gibson gave some beehives to his nephew, Adam, and his wife, Lucy Adamson, who lived near Hook, an area renowned for berry growing.

The beehives were required to pollinate Mrs Adamson’s berry crops and it signalled the beginning of her beekeeping career.

In the early 1930s, her youngest son, Bill, took over her beehives and shifted them into Central Otago, the move driven by the quality clover honey that could be produced on the Maniototo Plains.

Eventually, Bill’s two sons — Ernest and Walter — took over the hives, trading as Adamson Bros.

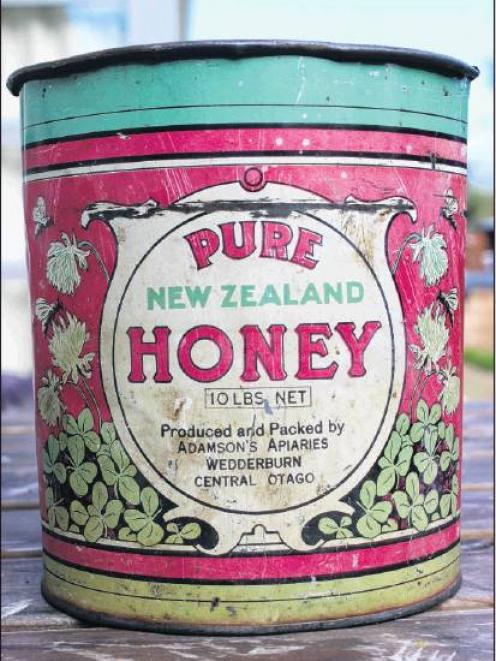

The business was eventually divided in two, with Ernest and his wife Ethel moving to Alexandra to operate Adamsons Apiary Ltd, while Walter still runs Adamsons Honey at Wedderburn.

Becoming involved in the family business was inevitable for Reece.

He grew up among beekeeping, learning about the industry ‘‘by osmosis’’ and worked for his father, Ernest, after leaving school.

He also worked in Canada for a season and then taught beekeeping in Tanzania, which was to prove an interesting experience, with an entirely different set of challenges to New Zealand.

Even though it was the same species as its New Zealand counterpart, the African honey bee was very well adapted to its natural environment and did not respond very well to being managed.

‘‘It made the challenges we face here seem quite straightforward by comparison, to try and work with bees that wouldn’t even stay in the beehive for more than a couple of weeks,’’ he said.

Mr and Mrs Adamson, who established Wildpure in 2008, have 500 beehives within a 100km radius including the Maniototo — ‘‘for sentimental reasons’’.

They still had some of Lucy Adamson’s equipment while the principles of extracting the honey remained the same as when she did it, he said.

Mr Adamson is a full-time beekeeper and they employ a full-time staff member, while Mrs Adamson does the administration work and helps out with raising queen bees in the spring.

They extracted their own honey and also extracted honey for several other beekeepers which kept them busy at the end of their main season, which started to go quiet about March.

In Otago-Southland, the commercial beekeeping industry had stabilised since varroa came through in 2011-12 which caused ‘‘a bit of adjustment’’.

Beekeepers had to learn how to manage the bee parasite and there would have been a few hive losses and challenges with that, Mr Adamson said.

While varroa was still an ever-present threat, it was now back to the ‘‘same old challenges’’ such as drought.

Commercial beekeeping numbers in Otago were probably static, but there had been a dramatic increase in the North Island due to the boom in the manuka honey industry.

As far as the secret to his own family’s longevity in the honey trade, Mr Adamson reckoned it was due to stubbornness.

Like all farming families, there had to be someone in the next generation who was keen to pick it up.

Looking ahead, if they figured out how to utilise lots of diggers and big trucks in the beekeeping operation, then 5-year-old son Jack would ‘‘be on board’’, he quipped.

As far as his own decision, it was probably due to the lifestyle and he much preferred being self-employed. Beekeepers were generally quite an independent bunch, he said.

Globally, honey demand was quite strong. China now took about 30% of New Zealand’s honey exports, up from about 10% just three or four years ago.

That was quite a remarkable statistic and was largely due to Chinese demand for manuka honey, although he suspected other monofloral types were getting benefits from that demand.

Clover honey has been in short supply due to dry seasons throughout the South Island over the past two years, which had helped to drive demand.

Mr and Mrs Adamson, who have their own export licence, were production driven rather than market driven.

They intended focusing on maintaining the resilience of their business rather than expanding, he said.

There would be challenges ahead, including likely resistanceto varroa treatments, whileland-use changesalso posedsome issues.

They had to keep an eye on land-use changes on properties where they had hives, as rotational crops posed a challenge for them, and increased irrigation was not necessarily an advantage for beekeepers. ‘‘There’s no honey to be made from swedes or ryecorn or lucerne.’’

Central Otago was the only place he was aware of in the southern hemisphere which produced thyme honey and it was produced by about six commercial beekeepers.