(Brett McDowell Gallery)

The American South is a world unto itself. It is a world of opposites; one of the acceptance of seemingly conflicting and bizarre cultural norms that can baffle and amuse those not brought up in the region.

Laurence Aberhart, on a tour of the States in 1988, noticed one such oddity. A region well-known for its conservative and fundamentalist views of religion is also the home of an astonishingly large number of fortune tellers, faith healers and tarot readers, all setting out their shingles by the highway.

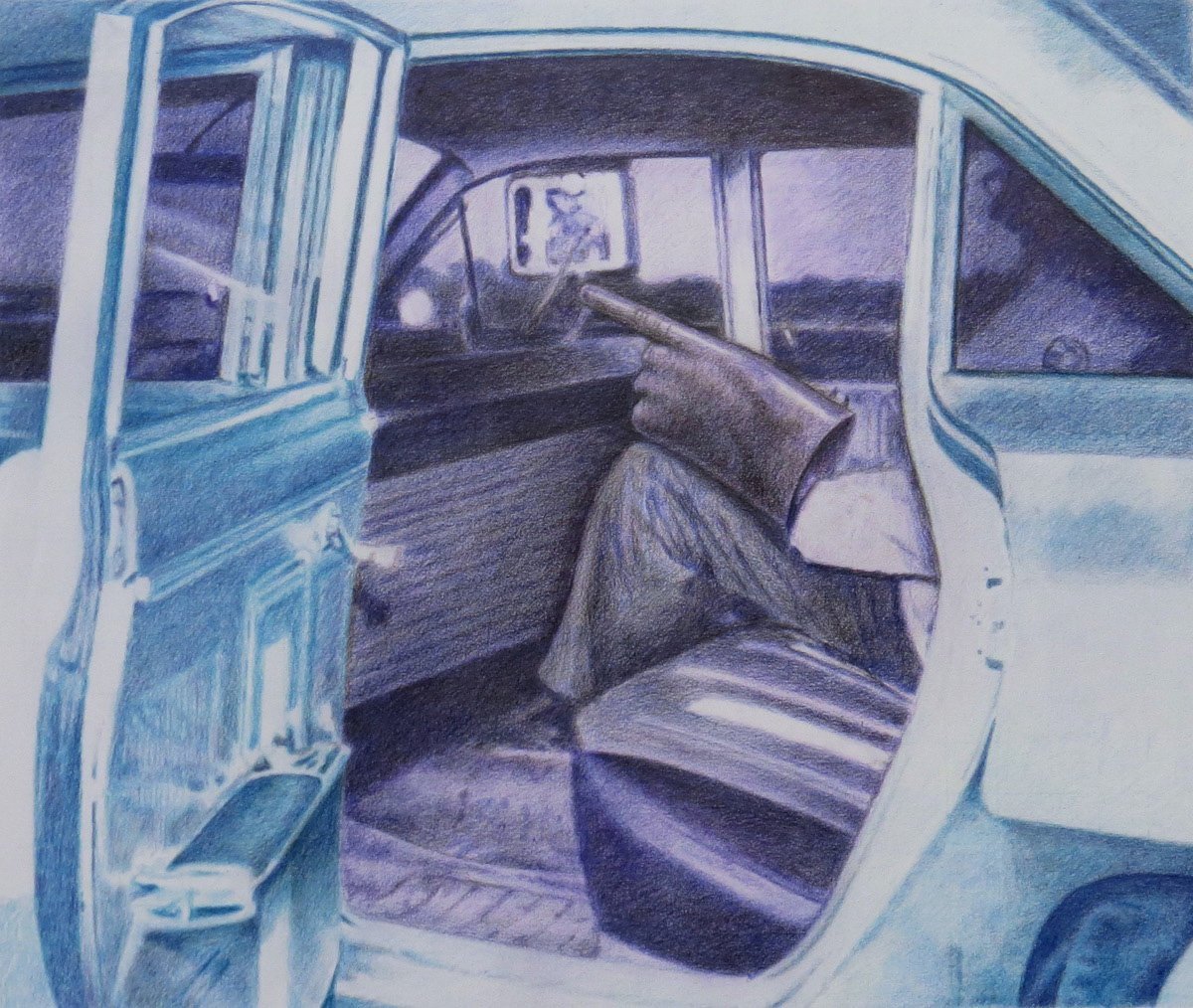

Aberhart decided to create a small series of his high-quality photographic prints based on these roadside notices, and they are impressive both as photographic works and also as a statement about 1980s America. We see the unusual juxtapositions of faith healers and neighbouring plumbers. We see the seeming ends of the wealth spectrum: the sturdy, well-built advertising sign in front of Sister Jackson’s nicely appointed suburban home sits alongside the less well-to-do home of Sandra, and Sister Sharon’s barracks-like prefab. And always the cars, the enormous late model cars.

Aberhart has completed the show with his own tongue-in-cheek juxtaposition, putting these photographs next to several showing the fascinating and sometimes unnerving architecture of another form of faith work, Southern Baptist churches.

(The Artist’s Room)

The Artist’s Room is commemorating its 18th anniversary with an epic group show featuring many artists who have long graced the gallery’s walls and also several new recruits, exhibiting in Dunedin for the first time.

There are many fine works on display. Notable among the pictorial pieces are a series of whimsical paintings by Alice Lin featuring humans dressed as rabbits, frame-within-frame animal and plant studies by Jane Siddall, James Watkins’ panoramic Central Otago view and some lovely interior studies by Sue Tennent. Other impressive two-dimensional works are on display by Kathrine Furniss, Tyler Kennedy Stent, Paris Sinclair, Jessica Ross, Philip Madill and Inge Doesburg. A softly blurred yet glowing photograph, a Stoney Creek landscape by Timothy Laffey, is also an exceptional work.

Among the more sculptural pieces, two wall-hanging nudes created from wire by Debbie Neill stand out. Daniel Wright’s flight of copper stingrays is also a strong work, as is Andrea Cooper’s Secret Keepers, a connected group of ceramics pieces attached to board. Light-hearted additions to the display come in the form of Tatyanna Meharry’s ceramic paint tubes and Pip Wood’s series of funky fungi. A more traditional, yet humorous, approach is taken with Queenie, a ceramic work by Deb Powell.

(Blue Oyster Art Project Space)

’Uhila Tu’ipulotu Nai’s exhibition at Blue Oyster is a process of mapping and discovery. Nai is using traditional and modern methods of creating Tongan ngatu cloth to explore her heritage.

As with much traditional cloth-making around the world, the work was done by women sitting around a table, sharing camaraderie and gossip as they worked — spinning yarns metaphorically, even though no actual physical yarn was present in the cloth-making. The creation of the cloth thus was often accompanied by the handing down of cultural history, and by the re-connection of women within extended families and neighbourhoods.

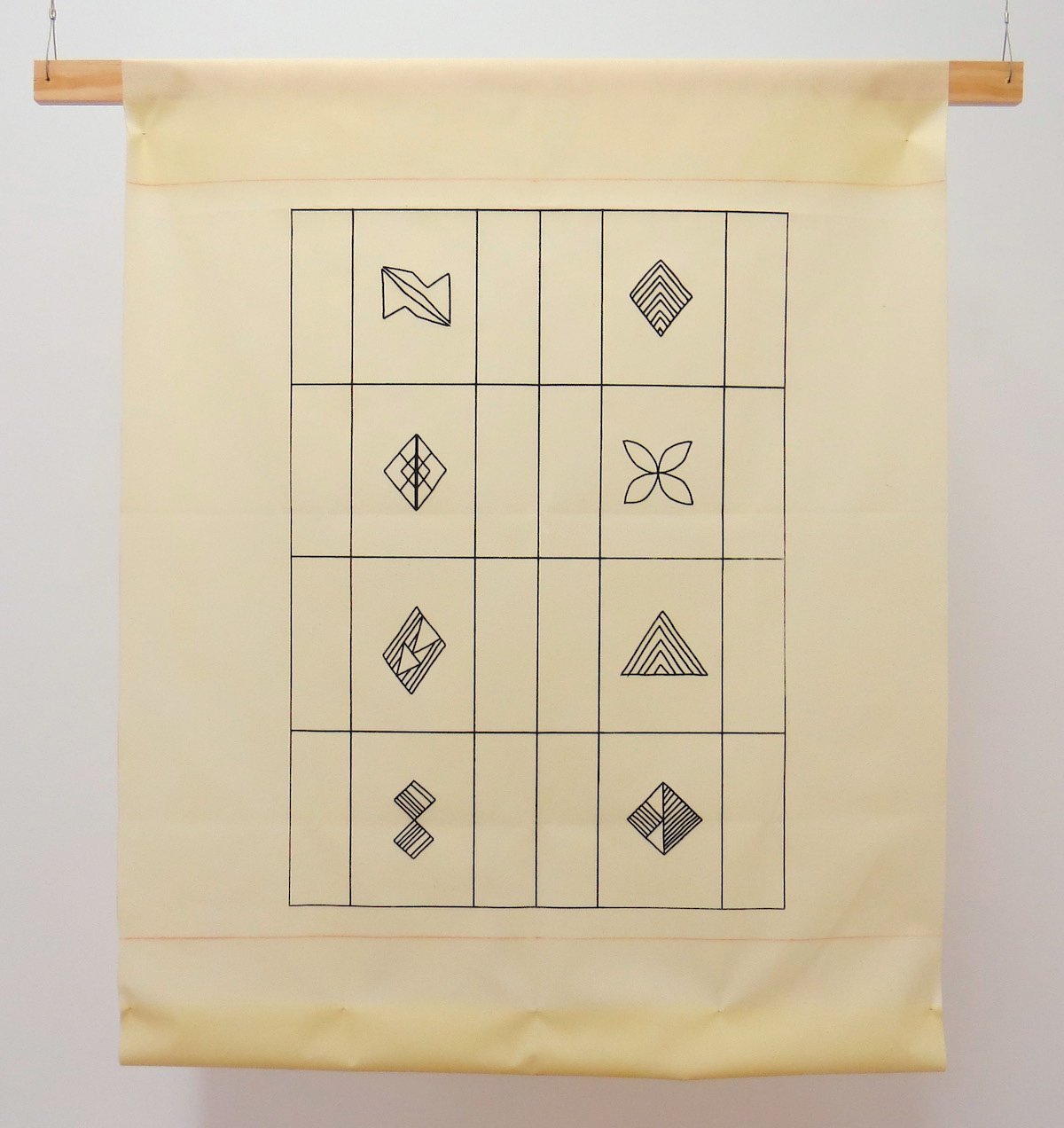

Nai has responded to this legacy with three sets of works. In the first, she has set up a cloth-making table within the gallery space, on which are displayed designs made in collaboration with other cloth-makers, including her nena, ’Ana Va’inga Nai. Some of the designs presented are traditional ngatu patterns; others are new or modified from traditional symbols. Several of these cultural hieroglyphs are presented on vilene paper in a second series of works surrounding the table.

The third series is perhaps the most intriguing; a series of maps showing the changes in a Tongan traditional neighbourhood over time, printed on vilene paper in a way deliberately reminiscent of ngatu symbolic style.

By James Dignan