(Fe29 Gallery)

Primarily comprising works from the late 1990s and early 2000s, this exhibition presents 39 works that feature the time Blair and her husband John Porter were living in Venice, California.

Spanning large-scale oil on canvas works, small gouache works and a selection of later vellum and ink on paper works, the focused breadth of this section creates an obvious sense of cohesion across the variable exhibition spaces in Fe29.

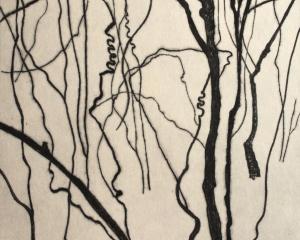

Blair’s work provides a rewarding immediate visual and affective experience. Each composition is a resolved delivery of energetic mark making and colour. Almost always with no fixed focal point, the viewer is effortlessly led around the composition in any number of directions, perpetually responding to the varied lines and components of colour, thick paint or wide brush strokes.

It has been documented that Blair’s art reflects the times and life contexts in which it was made. A small component of the exhibition includes slightly more subdued untitled works from 2020, and that incorporate vellum and very little colour. In contrast to the vibrant confidence of the works made in California, and possibly Florence, Italy, the mood of this work is troubled, with sharp lines that appear imprinted into the surfaces.

![Intersection [installation view], featuring Ana Terry and Anita DeSoto. Photo: Justin Spiers](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/story/2025/06/intersection_j_o.jpg)

Four quite different art practices comprise this group exhibition by the founding members of the feminist Women’s Work Art Collective (WWAC).

Her Fertility Turned His Heart to Stone (after Jordaens) (2023), by Anita DeSoto, is a critical and historical response to the depiction of women in Jacob Jordaens (1593 –1678) work. Desoto edits out the men and reframes the image with an empathetic focus on the women present in the work.

Ana Terry’s Leviathan (2025) is a triptych image of a monstrous pile of vehicle tyres, twisted and tied together. The work is printed on aluminium, adding a metallic sheen to an allusive reptilian form. In what is a visual metaphor for systemic power structures, Terry considers the broader political frame.

Linda Cook’s sculptural paintings enfold care and attention as deliberate and critical approaches to reused materials and the process of making. Cook speaks from the lived experience of a working-class context in the 1960s and ’70s and to the generational effects of traditional societal constructs of women’s roles.

Emma Cook is a poet and has made an installation of hand-made books with embroidered covers. Each book is a unique collection of poems, with an individual cover (a spider, a key, or red roses, for example). In the tropes and heritage of feminist art, Cook’s work has, in the artist’s words, a "Gothic domestic" sensibility.

(Slant Art Project Space)

"Siva in Transit" is a witty and critically engaging installation with focus on fa’afafine identity and the problematics of exoticisation and commodification. Alvin Kumar is of Sāmoan and Indo-Fijian descent and is currently working towards a bachelor of visual art at Te Kura Matatini ki Otago, the Dunedin School of Art.

Kumar’s exhibition comprises a central figure, with long pink fake fingernails, plastic ‘ula (necklaces), and is constructed with the use of plastic striped woven bags (an item often colloquially associated with the Pacific diaspora). Gracefully poised mid-dance (siva means dance), the figure is titled "Big Juicy" and stands tall among larger-than-life-sized cans of food.

Communicating critical anchor points for the work, Kumar encodes humorous wordplay in the label of each can: Palm’s Corned Beef is known is Kween Beef, containing 110% Iron(y), for example; and a can of Kara’s Coconut Cream contains 10g of Total Phat (gauguinified) and 47g of Colonial Residue, for example.

"Siva in Transit" makes a reference to Yuki Kihara’s layered work Siva in Motion (2012), where Kihara performs a traditional Sāmoan dance form, the Taualuga, in Victorian mourning dress. Kumar employs a visual language that chimes with Kihara’s work, yet is uniquely and vibrantly contextualised by their own lived experience and observations.

By Joanna Osborne

![Marama [detail] (2025), Whaka Oho Rahi and Benhar clay, salvaged glass from Ōtepoti harbour and...](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2026/02/1_jess_nicholson.jpg?itok=q3eXu3xD)