(Gallery De Novo)

Those who are familiar with Eliza Glyn’s work might be surprised by the artist’s latest exhibition. Although best known for her meditative stylised landscapes, Glyn has moved into new fields which have allowed her to free up her style, and she has done so with panache.

Most of the works in the display are gentle gouache still lifes, each focusing on items of dinnerware. The artist has described these as snapshots of her table at home, and there is a loving domesticity to these images. The works also provide a homage to Glyn’s artist friends, as the tableware on display is largely composed of hand-made ceramics by favourite potters. In several of the cases (such as Amanda Plate and Katherine and Dara) the ceramicists’ names provide titles for the works. Several impressive if more traditional floral still lifes in oil or gouache are also present, notably the large prosaically named "Flowers".

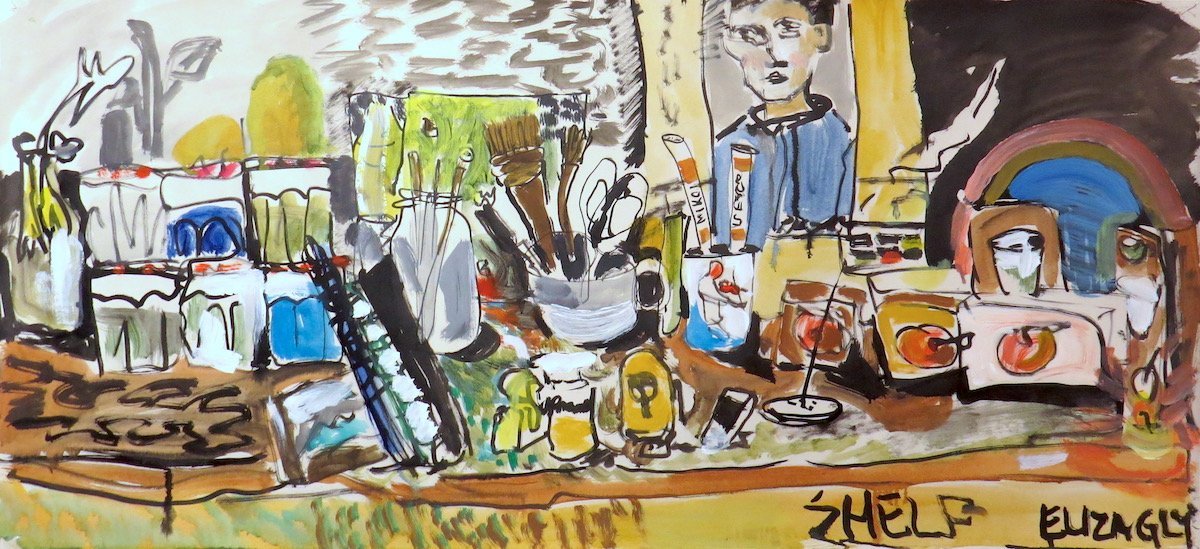

The artist has freed up her style with several wilfully sketch-like studio scenes. These works feel like catharsis, especially when placed close to a small array of Glyn’s more familiar landscapes. The contrast between the mannered hills and the vigorous studio images is strong, almost to the point where you feel that the calm is only possible if the coiled tension is allowed to occasionally break.

(Fe29 Gallery)

An old family diary from the 1890s has set artist Amy Melchior on a journey of self-discovery and artistic recognition of a family lineage. Melchior has used the journal as inspiration for an extended series of works which honour and immortalise her family tree, and especially the women of her line, acknowledging the hardships they endured and the memory traces they have left to posterity.

Melchior has used encaustic painting, a method which employs wax as a primary medium, and has created mixed-media works by a process of embedding and adding elements to the pieces, ranging from old letters and photographic prints to lace, rust particles and even lichen. The resulting images are like frozen moments, forever enclosed in amber or kauri gum. The natural honey-like sepia glow of the encaustic adds to the feeling of a lost time, faded photographs of a beloved ancestor captured in life, and the soft warmth of the medium perfectly captures the heartfelt love with which the works are imbued.

As museum pieces, the individual constructions are fascinating and full of ephemeral historic detail. As art, they succeed both on an aesthetic level, and also in their designed purpose — to memorialise and capture the essence of a sacred personal whakapapa.

(Olga)

There is a seeming bright innocence to the vibrant paintings of Felix Harris, but it is one that hides deep waters.

In the artist’s latest exhibition at Olga, he presents a series of almost fluorescent works in which bright images are paired with often sloganistic or polemic titles (Death to the Dictator, Seize the Day), giving what initially seem gleefully joyful works a frisson of sinister undercurrent. Harris examines the world and its woes with a cynical eye, filtering them through mass culture (many of his titles are taken from film titles and quotations), turning them into a personal landscape, creating his own "good enough world". The gestural neo-expressionism of the art ties his work closely to that of several other artists within Dunedin and its environs, from James Robinson to Ewan McDougall, though understandably Harris’ own familial artistic upbringing (as the son of Jeffrey Harris and Joanna Paul) has also tempered his practice.

Harris’ great gift in these works is his ability to somehow combine opposites. Each work is a sum of evocations of exuberant happiness, unsettling disquiet, simplicity, complexity, vivid brightness and philosophical depths, leaving the viewer with decidedly mixed emotions from the art which change with every viewing.

By James Dignan