In this week's Art Seen, Robyn Maree Pickens looks at exhibitions from the Milford Gallery, Seraphine Pick, and the Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

Casing, by Phil Brooks

''New Works'', Group Exhibition (Milford Gallery)

Casing, by Phil Brooks

''New Works'', Group Exhibition (Milford Gallery)

From the heaviness of basalt to the pollen-like lightness of glitter, New Works is a celebration of medium and texture. Two large sculptures in the form of necklaces by Chris Chateris anchor the exhibition.

One is made from South Canterbury greywacke and Southland granite (Tuaiwi 2019) and the other from Coromandel granite (I Love My Friends 2019). At the other end of the gravity/mass spectrum are Reuben Paterson's glitter works (sculptures and framed mixed media glitter fields), which are roiled into atmospheric swirls caught as if in mid-transformation and poised for flight.

Occupying the middle register of weight are cast glass sculptures of bird forms and bird-like vessels by Mike Crawford. The red of two Crawford sculptures finds an echo in large, red geometric bands that dominate Leanne Morrison's abstract, acrylic and enamel paintings. Even when a red band is sunk behind burgundy it still comes to the fore.

The standout work in this exhibition for me, however, was a selection of ceramic works by Auckland-based artist Phil Brooks. These hand-coiled, built ceramics in light earth tones play with recesses and extrusion to create small-scale architectural forms that are perfectly formed and complete.

Two recessed world-within-world works - in particular Casing (2019) - embody a secluded holding environment, as if a small vessel were capable of embrace and nurture.''Corporeal'', Seraphine Pick

Corporeal VII, by Seraphine Pick

‘‘Corporeal’’, Seraphine Pick (Brett McDowell)

Corporeal VII, by Seraphine Pick

‘‘Corporeal’’, Seraphine Pick (Brett McDowell)

In a world increasingly oriented towards artificial intelligence and digital embodiment, what significance does the human body retain? Seraphine Pick's latest suite of 10 paintings, all titled Corporeal, seem to be engaged with this question.

Over the past few years, various characters in Pick's figurative paintings have adopted specific accoutrements of digital and virtual reality environments, such as VR headsets.

Although undoubtedly still in dialogue with digital, networked and augmented realities, this suite of paintings feels grounded in the body, even as Pick's mark making in some paintings suggests a fracturing, if not shattered world.

Corporeal is testament to Pick's extraordinary range as a painter who can move deftly between carefully built fields of colour, such as Corporeal XIII (2019) and an extreme economy of mark making, as in the sparsely conjured female form and tree of Corporeal III (2019).

These short, brisk brush strokes to delineate forms are something of a revelation in this latest exhibition, superseding the long, serpentine lines of earlier paintings. They also demonstrate Pick's superb sensibility as a colourist.

In Corporeal VII (2019), Pick's juxtaposition of charged colour of post-impressionist-style brush work to form a scalloped halo around the delicately materialised central female subject achieves an uncommon radiance. Corporeal makes a plangent call for earth-bound embodiment.

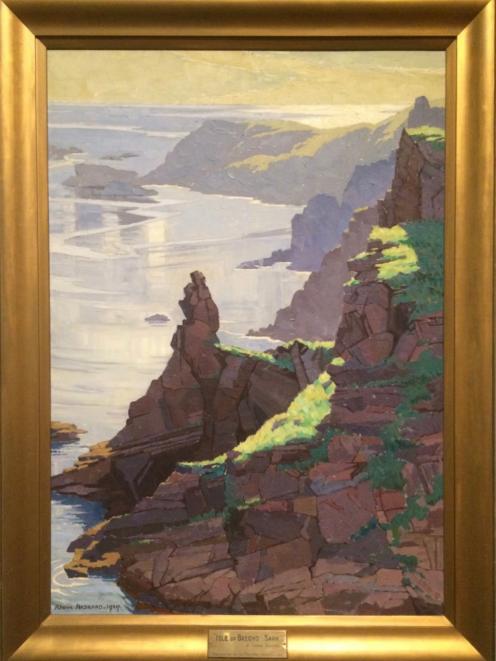

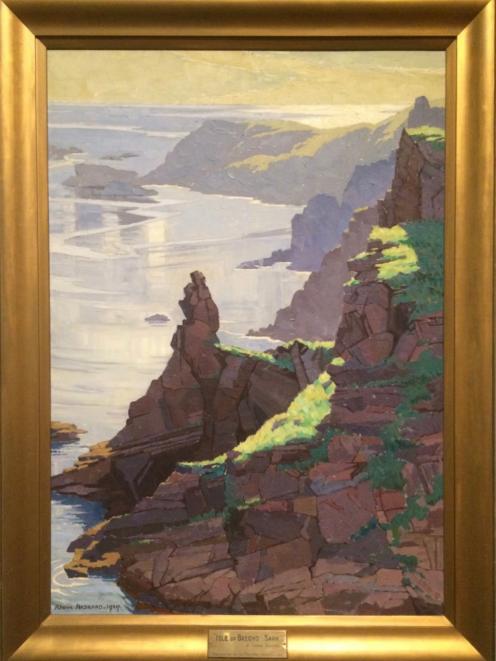

Isle of Brechou, Sark, by Rhona Haszard

''Style and Substance'' (DPAG)

Isle of Brechou, Sark, by Rhona Haszard

''Style and Substance'' (DPAG)

One of the most enjoyable approaches to a large collection exhibition such as Style and Substance, which is divided into six distinct themes (landscape, animals, genre, still life, portraiture, history), is to find your own narrative, navigation, and favourite works.

There is, for example, a terrible poignancy for the contemporary viewer of Arthur Wardle's Where the Ice King Reigns, located in the Animal section of the exhibition. Painted in the early 20th century, Wardle's oil painting depicts four polar bears on solid polar ice.

It would have been unimaginable 100 years ago that the thick ice girding the Arctic North might become ephemeral, and the existence of polar bears tenuous. In many ways Wardle's imprecise representation of this once-frozen world, with the family of four based on caged polar bears from the London Zoo, prefigures the outcomes of a controlled and subjugated natural world.

Taking this ecological slant, one can wonder how our representations of the rest of nature influence our interactions. What does it mean, for example, to move towards a ''flattened'' nature, as seen in the foreground treatment of rocky cliffs in ex-pat Rhona Haszard's Isle of Brechou, Sark (1929)?

On the one hand, Haszard's painting is masterful, striking and an important exemplar of early modernist painting. On the other, what are the repercussions of flattening, deconstructing, and fracturing landscapes?

-By Robyn Maree Pickens

![Untitled (c. mid 1990s, [pink 3]), by Martin Thompson, 415mm×590mm. Photo: courtesy of Brett...](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2024/02/untitled_pink_3.jpg?itok=Q0aQrc9o)