Walking along the shore and the forest paths of Whakanewha on Waiheke Island, Clive Humphreys often has moments where he is literally stopped in his tracks.

The quality of light, colour, forms, reflections and shadows in front of him has created a sense of wonder, bringing him to a standstill.

It reinforced what the former Dunedin Art School head (2017-19) realised when he moved to Waiheke Island seven years ago — that his monochrome drawings and watercolours needed to become colour.

Whakanewha is a regional park, home to native bush, coastline and many different types of seabirds and has a long history of Māori occupation.

"It’s an incredibly special place but it’s fragile and requires some looking after. And between the bush and the shoreline they have mown a passage of grass to deter predators from reaching the beach from the forest. And it creates this sort of lovely natural break between the water and the bush. It’s a magic place."

Humphreys describes the park as not only a sanctuary for birds but for him too and his work, as his exhibition "All in All" being shown at Dunedin’s RDS gallery shows.

"So I’ve walked there. And really this exhibition, in terms of content, represents a regular walk that I do."

He now sees the black and white works he was doing before he moved to the island as preparation for the works he has since done in colour.

Two years ago many of those early works were shown on Waiheke Island in an exhibition called "Between Showers". Many works focused on the ravages of weather on his walking path.

"There was a lot of flooding and a lot of surface water. And it made me become sensitised to the idea of the way in which reflection will draw in aspects of the landscape which are not necessary in the picture. So I very rarely paint the sky, but often the sky is present in the reflected water.

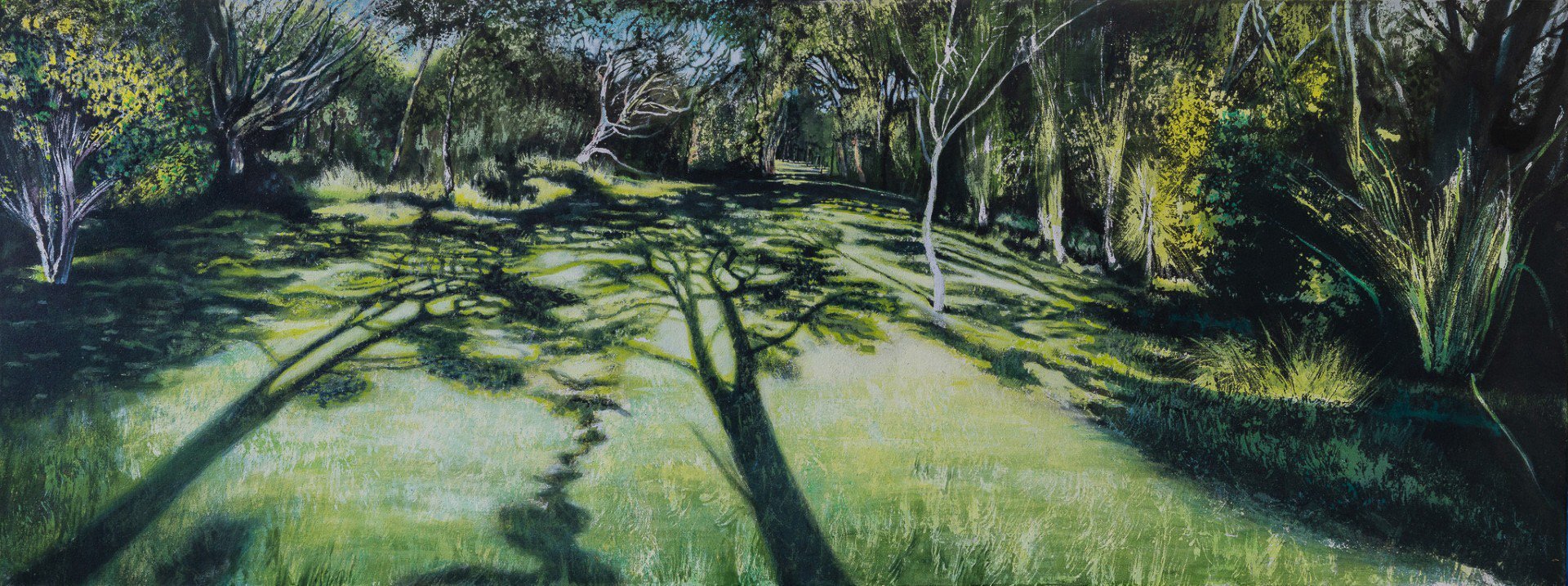

"And you get this feeling of immersion in the paintings, which comes from almost being aware of what’s behind you. Because, for instance, in this painting, you can’t see the tree behind you, but you see the shadow that’s projected. So it’s almost like when you’re in the bush — there’s this feeling of being surrounded.

"And it comes from the things, in fact, that you sense, but you don’t necessarily see. I have attempted to capture some of that in the painting."

"The printmaking techniques that I used have kind of transferred and translated into techniques that I’ve used in the paintings."

While his subject may have remained the same for the past 15 years, his practice has never remained static.

"So although I say I’ve spent 15 years painting this place, or drawing this place, it’s always moved with every, probably with every, body of work that I’ve made from it. And either the materials move or the way I look at things move.

"It seems to move less and less. Some of these paintings are all the same place. You just take 10 paces to the right and you’ve got a completely different thing in front of you. I feel like this is such a rich place that I don’t need to travel anywhere.

"The idea of making an in-depth investigation into one place, where I move around about 5m every time, that appeals to me somehow. It feels not constantly looking for the thing. It’s actually there. You just have to shift your perception."

Humphreys has always drawn from on-site drawings and still carries a sketchbook with him but is finding more and more often he wants to work in the studio.

Part of that is the time it takes to complete a painting. His large panorama works in acrylics on canvas take months to finish, while his smaller works on paper take weeks. His Dunedin exhibition took a year to complete. He also often works with a paintbrush in one hand and a hairdryer in the other to enable the work to dry quickly.

"So there’s a necessity to work in the studio. And I think also once the painting gets to a certain point, it’s no longer helpful to be looking at the source material. The painting has an impetus of its own, which I need to deal with.

"At that stage, memory of the place, and the whole texture and sensation of the place, is more important than the minutiae of the detail. And the process of painting is one of translation; it’s moving from sight into tactility of the mark-making. And so you’re always looking for, not to reproduce what you see, but to think about equivalence of mark-making that one can make."

Living on Waiheke, Humphreys gets to do what he always said he would do when he retired — paint fulltime.

"It feels like you can relax into the work more. So I have a routine of meeting friends for coffee before I start in the morning and I can paint for about five hours before I start to flag. I say paint but a lot of that time is sitting still staring at what I’m doing trying to work out what it means and how I’m going to fix what is wrong."

"I don’t do well in big cities. So I was also feeling the need for change."

He remembers an art scene in Dunedin just starting to gain momentum in the mid-1970s and ’80s, much of it centred around the Bosshard Gallery in Dowling St.

"There was a real energy in the galleries."

Humphreys, who studied three-dimensional design (prior to computers) at art school but had moved into printmaking by this time, was lucky enough to secure a large studio space in the same street as the space used by band Toy Love as a practice room.

"They [studio spaces] were everywhere. And you could rent them for a song really. And they were often spaces that had been abandoned by music groups. Dunedin was a great place to work."

Back then, he was working on the rubbish trucks. The early start and finish let him continue painting. It worked for 19 years until the odd bit of work he picked up at the Dunedin School of Art became a part-time job.

"I finished up at art school by accident. One year I was teaching some screen printing, which Grahame Sydney had asked me to do. And the next year he said ‘would you like to take the class over?’."

While the hours crept up and he moved from teaching diploma to postgraduate level, he always made sure he had some time in his studio. Even when he was appointed head of school, "a sort of natural evolution", but also a job he "reluctantly" took on, he kept painting and maintained oversight of his postgraduate students.

"That was really important. It seemed important to me that I should be working. I should be doing what I was teaching. And keeping in connection with the way students were thinking, the way students were working, what was going on at the kind of coalface level of the school."

His time at the Dunedin School of Art confirmed his thinking that art schools did not teach a person to be an artist. They provide a liberal education in the arts, preparing a student to think critically in ways that could be used in many different vocations.

"I’m distressed at the demise of the humanities for instance. All over New Zealand because I think that the fundamentals of the humanities are about critical thinking.

"And we need more of that not less of it."