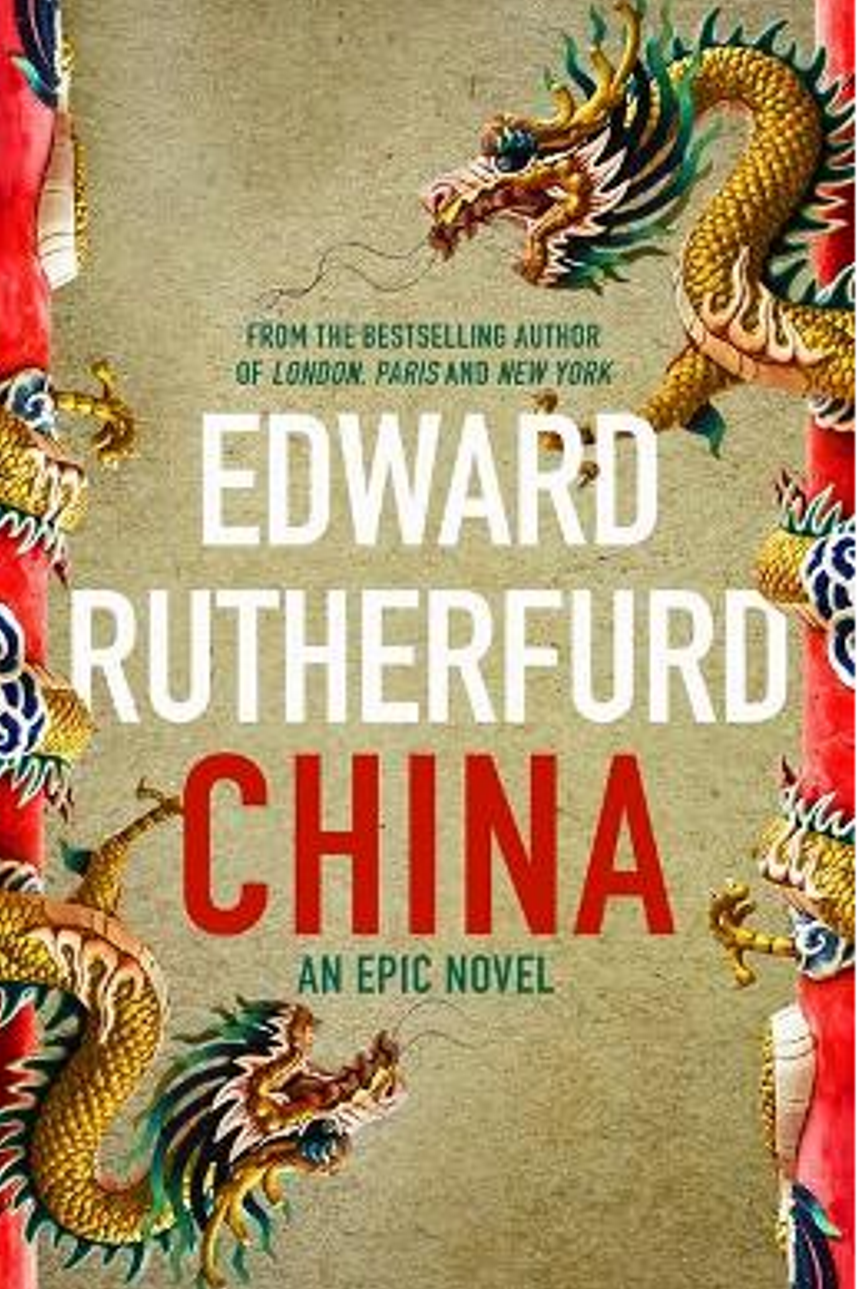

CHINA: AN EPIC NOVEL

Edward Rutherfurd

Hodder & Stoughton

REVIEWED BY PETER STUPPLES

Edward Rutherfurd writes novels that elaborate the history of cities through the lives of fictional characters caught up in the netting of significant historical events. China is no exception, though the netting is one of time rather than a particular location.

Its span reaches from 1839 until the years immediately following the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901. The fictional characters, European and Chinese, are all caught up in the political and military vortices of the two Opium Wars, the Taiping and Boxer Rebellions, that were themselves consequences of European predatory trade, exploitation, missionisation, political and military humiliation.

In addition to the historical events, we also learn a great deal about Chinese culture: the Confucian ethic and social structure, class and ethnic divisions, footbinding, becoming a eunuch serving the imperial court, the rivalry between the Manchus and Han Chinese, even ikebana.

The novel tells interlinked stories of Europeans engaged in the opium and tea trades, at first centred on Canton, but over time spreading to other coastal concessions, including the establishment of the city of Hong Kong.

We are introduced to John Trader in Calcutta, where he falls in love with the daughter of a military man who regards him as an unsuitable match - no money, no class, no connections. Trader is determined to win his bride by making a fortune in the opium business. To do so he goes to Canton and Macao and we are introduced to the nexus of the Wests exploitation and Chinese weakness. The barbarians, as they called Westerners, force concessions at every turn.

Trader makes his fortune, but he is no naive observer of China’s grief. Towards the end of the novel, now an old man, he experiences the siege of the British legation in Peking during the Boxer Rebellion, during which he writes a memorandum, commenting on the West’s mistakes in China during the 19th century: ‘‘We need to help the Chinese, not punish them. Call it enlightened self-interest, call it anything you like. But that’s what we should do.’’

We learn about the positive side of the Chinese Confucian-inspired civil service through the life of Shi-Rong, observing orderly governance through the example of his conservative mentor Commissioner Lin. However, though Lin never takes bribes, those around him do so increasingly as the Empire begins to fall apart, particularly under Western pressure.

Partway through the novel, third-person becomes first, as Lacquer Nail tells his own story: his frustrated ambitions lead him, though a married man with children, to become a eunuch, in order to pursue a career within the Forbidden City, the Imperial palace network in Peking. He is a chancer, contriving to take advantage of every opportunity of advancement within the very competitive world of palace politics, when he becomes manicurist to the emperors Noble Consort Yi, later the Regent-Empress, Cixi. Through Lacquer Nail we are able to watch machinations within the court at close hand.

These fictional characters, and many more, both Western and Chinese, bring history to intimate life. The pace never slackens. There is plenty of excitement - skullduggery, murder, sleaze, arrogance, bravery, Lord Luck.

We are encouraged, along the way, to contemplate Western aggression in the 19th century across the globe; the events in China, after all, paralleled the colonisation of India, Africa, Australasia, with the same violence and exploitation. The Christian churches were active participants. What if Trader was right, and the West had tried instead to understand others rather than regarding them, like the Chinese did Westerners, as barbarians? And what about our relations with China now? Is there something to be learned here or is this book just a racist romp?

Peter Stupples, now living in Wellington, used to teach at the University of Otago