Waiting for his flight, Max Rashbrooke steps outside the noisy airport terminal to take a phone call from a journalist who wants his thoughts on poverty.

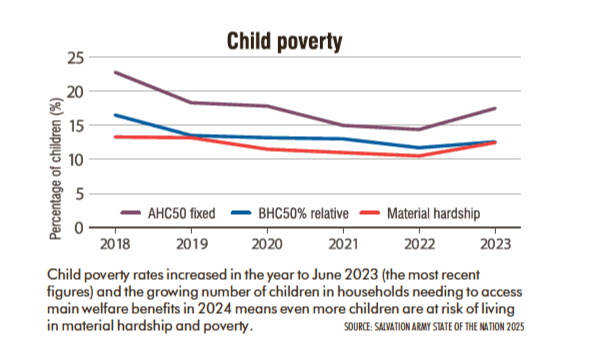

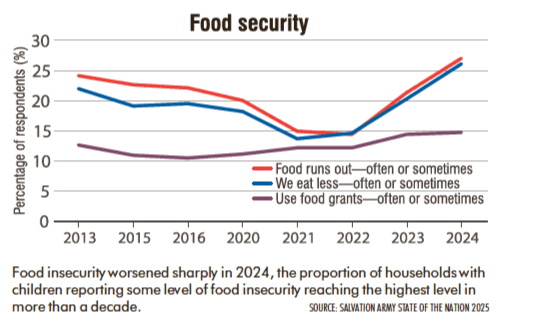

The Salvation Army’s latest State of the Nation report has revealed childhood poverty rates are up, unemployment is rising steadily and the number of people needing welfare support is the highest it has been in three decades.

Yes, Rashbrooke confirms, poverty is the daily reality for about one in eight, or 12% of children in Aotearoa New Zealand.

‘‘And that’s real, measurable poverty,’’ he adds.

It is the sort of poverty where children are growing up in damp, mouldy housing that can give them fatal respiratory illnesses; houses where fridges are switched off to save power; where food runs out constantly; where there may not even be a house; and the constants are deprivation, illness and despair.

‘‘That’s the life for about one child in eight in New Zealand. If you add it all up, that’s enough to fill Eden Park three times over ... so the entirety of the population of Dunedin.’’

And, perhaps because of where he is standing, Rashbrooke reaches for a story of poverty related to an airport.

‘‘I do go and talk to ... people who are really struggling.

‘‘There are houses you go into where there’s almost nothing in them. There’s barely furniture. There’s very little food in the fridge.

‘‘And there are also heart-rending stories about in-work poverty.’’

There was a woman Rashbrooke interviewed who lived with her children in sub-standard housing in South Auckland and could only get a job at the airport.

‘‘At one point, she lived in a house that had a broken water pipe and the carpets were constantly damp.

‘‘Think about the health problems that come from damp respiratory conditions.

‘‘There are lots of developed countries where they don’t really know what rheumatic fever is, and yet we have these very elevated rates of it because our housing is of such terrible quality.’’

Public service staff also treated her with disrespect.

A sole parent of school-aged children, she spent two hours each morning getting her children to school and herself to work. And then another two hours each evening getting home.

‘‘She was just utterly exhausted and she was constantly having health collapses.

‘‘It was an absolutely exhausting life with no real quality of life and constant health problems for her and her children.’’

Compare that one-in-eight statistic, Rashbrooke says, with childhood poverty rates in the most egalitarian countries. New Zealand has up to four times as many children in poverty compared with the likes of the Netherlands and Scandinavian states.

Another disparity, he says, exists between Aotearoa’s children and its seniors. About 4% of those aged over 65 are living in material hardship whereas, for households with children, it is three times higher.

‘‘So we have very elevated levels of poverty, which are obviously avoidable, because they’re vastly lower in other countries and they’re vastly lower among the over-65s.

‘‘I see and hear these stories and it’s impossible not to be affected by them personally. I mean, they are really heart-rending stories.’’

With these stories and statistics ready to go, matched with passionate concern and advocacy, it is no wonder Rashbrooke is the go-to commentator on poverty. But how did that happen?

‘‘Well, I’ll tell you what, it wasn’t through growing up in Eastbourne — because that’s quite a well-off part of the world,’’ he says with a chuckle.

However, his upbringing in one of the most affluent Wellington suburbs was in a family that did not shy away from social issues.

Rashbrooke’s parents sent him to an out-of-zone, lower-decile school, in Lower Hutt, to give him a broader perspective on life.

Going to a secondary school where many of his classmates were from struggling families was eye-opening, he recalls.

‘‘It really underscored something I guess is fundamental to the mission of my work now, which is that I had an incredible upbringing but a lot of other children don’t. And what I would like to see, is a world where every child has the same quality of upbringing that I had.’’

In 2009, the year before returning to Aotearoa, he read The Spirit Level, which shone a global spotlight on economic disparities and the damage they do, including in New Zealand.

Writing on the topic led to him editing Inequality: A New Zealand Crisis.

The next year, 2014, he was made an honorary senior research fellow at Victoria University of Wellington. It is a title he has held ever since, paying the bills through a mix of research, writing and speaking — such as his upcoming appearance at the Wnaka Festival of Colour, in early April, where he will be in conversation with investigative journalist Rebecca Macfie on the topic ‘‘Poverty by design’’.

‘‘I probably still feel like a journalist at heart,’’ he says.

It has served him well in his work uncovering the extent and impact of poverty in this country, as well as understanding its causes and thinking about cures.

Life in New Zealand was by no means perfect prior to 1984, Rashbrooke admits.

But, he says, the changes wrought by ‘‘Rogernomics’’ and ‘‘Ruthanasia’’ — the neoliberal, structural economic changes wrought by Labour’s Roger Douglas and then National’s Ruth Richardson; slashing social welfare benefits, cutting top tax rates, stopping most state housing construction and decimating trade unions — certainly set the stage for a much more unequal New Zealand.

‘‘Between 1984 and 1999, incomes for the poorest half of New Zealand, the entire bottom half, went backwards.’’

Since then, it has been a mixed picture.

By the three main measures, we now have between 150,000 and 200,000 children living in poverty.

‘‘The big story is, a huge amount of poverty was created when we slashed the State in the ’80s and ’90s. We’ve reduced those levels of poverty a little bit, but we’re still at a much higher level than the best-performing countries in the world and the countries that really look after children, in particular.’’

He points to the wealthiest paying a lower income tax percentage than those who stack supermarket shelves; this, he says, is part of the reason why New Zealand cannot properly fund health and education.

‘‘It’s mostly because we don’t have a capital gains tax, so they’re earning huge amounts of income that they don’t pay tax on.’’

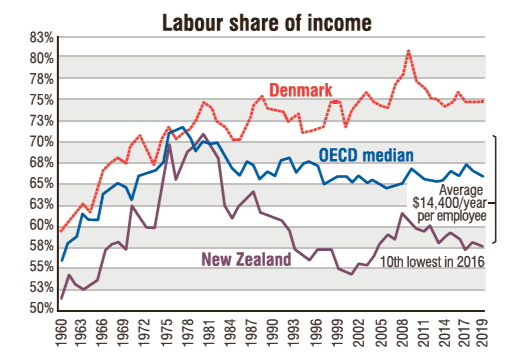

He details the past three decades’ big shift in the distribution of company profits from workers to owners.

‘‘The average wage would be about $12,000 higher now if company revenue still went to workers in the same way that it did in 1990.’’

He believes poverty is fundamentally about failures of design in our economic system.

‘‘We have built an economy that delivers a lot of its rewards to people who are already doing well and doesn’t reward people at the bottom for their effort and hard work.’’

Yes, personal responsibility is part of the equation, agrees Rashbrooke, but the big change since 1990 is not that people at the bottom have become lazier and more stupid while those at the top have become more talented and hardworking.

‘‘Four out of 10 children who are in poverty have a parent with full-time work.

‘‘As with the woman in Auckland driving two hours to get her kids to school and herself to work, there are so many barriers we put in the way of people who are trying to lift themselves out of poverty.’’

He says people in poverty have often grown up in difficult and abusive situations, without enough done to help them through their childhoods. Then we do not properly invest in their education or provide them with the housing, transport and healthcare they need.

He cites a study showing a sudden, unexpected financial shock, for someone living in poverty, has the same negative impact on decision-making as a whole night without sleep.

‘‘Being poor makes it very difficult to make good choices, even when there are good choices available, which there aren’t always.

‘‘So, my view about the personal responsibility issue is, yes, I’m absolutely happy to have that discussion once we have removed all the structural barriers that are in the way of people making the right decision.’’

The journey to a better, more equal Aotearoa will not be easy, Rashbrooke warns.

‘‘There’s no one simple answer. Sometimes people pretend like there is, but I’m always very suspicious of that.’’

Instead, he advocates for a broad and deep reconfiguration of our economy.

‘‘I think we need to reorient the economy, very fundamentally, towards investing in people.’’

He estimates the annual cost of child poverty is more than $10 billion.

‘‘Think about how many entrepreneurs we lose every year because children are growing up in poverty and they either die or fall incredibly sick from respiratory illness, or their home life is so difficult there’s no way they’ll ever do well at school.’’

Building an economy from the bottom up would include investing more in education, especially in low-decile schools, and investing more in skills and retraining.

‘‘When people are on benefits, compared to other countries, we don’t put a lot of time and effort into helping people find paid work. And I don’t think New Zealand firms generally invest enough in their staff.’’

None of that is likely to happen, however, until ‘‘middle New Zealand’’ sees poverty as a serious problem needing urgent action, Rashbrooke says.

He gives the example of Wellington residents who live just a half-hour drive from each other but have a 10-year difference in life expectancy. The increasingly segregated lives people live mean those who are comfortable rarely come in contact with those in poverty.

‘‘I think that fundamental reorientation of the economy will only occur if we can find a way of reconnecting middle New Zealand with the actual lives that are being led by people in poverty — so that middle New Zealand can understand actually how difficult it is, how by-and-large it isn’t people’s fault individually.’’

Rashbrooke is trying to find ways to bridge that gap.

‘‘Obviously, I’m not going to do it by myself ... but it is something that I’m talking to various groups and individuals about.’’

It does beg a question though.

In an increasingly segregated world, given his background, Rashbrooke probably has a good chance of living comfortably without needing to interact with, or concern himself unduly about, those living in poverty.

So, why does he bother?

‘‘For me, people’s opportunities to live a life that would be beautiful and deep and rich and meaningful - for that to be taken away from them by poverty is just so incredibly depressing and tragic and sad.’’

And it is unjust.

‘‘Why should I have had a great childhood and not someone else?

‘‘It’s so utterly, utterly unjust that these children will have so much taken away from them by poverty. It's totally avoidable and it will have such a long-term effect on their lives.

"I guess I'm just not someone who's prepared to walk on by."

The talk

Max Rashbrooke discusses ‘‘Poverty by design’’ with journalist Rebecca Macfie as part of the Wānaka Festival of Colour’s Aspiring Conversations.

Pacific Crystal Palace, Ardmore St, Wānaka.

Saturday April 5, 1pm.