Liam Scaife searches the colourful graph in front of him with a fierce intensity, interrogating the converging lines for signs of hope.

A dun wedge narrows left to right along the x-axis, which denotes time. That’s good, but is it enough? So much hangs on it.

Another of the plotted values does the reverse, widening as it tracks right. This is what must happen. But will it make the difference?

Does the data mean extinction or survival?

Surely this is too much to expect of a graph. Equally, it is too much to ask of a 16-year-old, as Liam is, to expect him to find salvation between the legend and the plot.

But then, Liam has asked this sort of feat of himself before, on a cold autumn morning amid the workaday breakfast-show bustle. As the city’s commuters went through their heedless rituals, he stood on the Dunedin Railway Station tracks, staring down a coal train. Just him and two friends, allies, a thin line of vulnerability arranged against the industrial juggernaut.

There was then, for the briefest time, a victory. The coal stopped, the train reversed, its headlight receding.

Liam now wants this graph to tell him the train will abandon its fossil cargo for good.

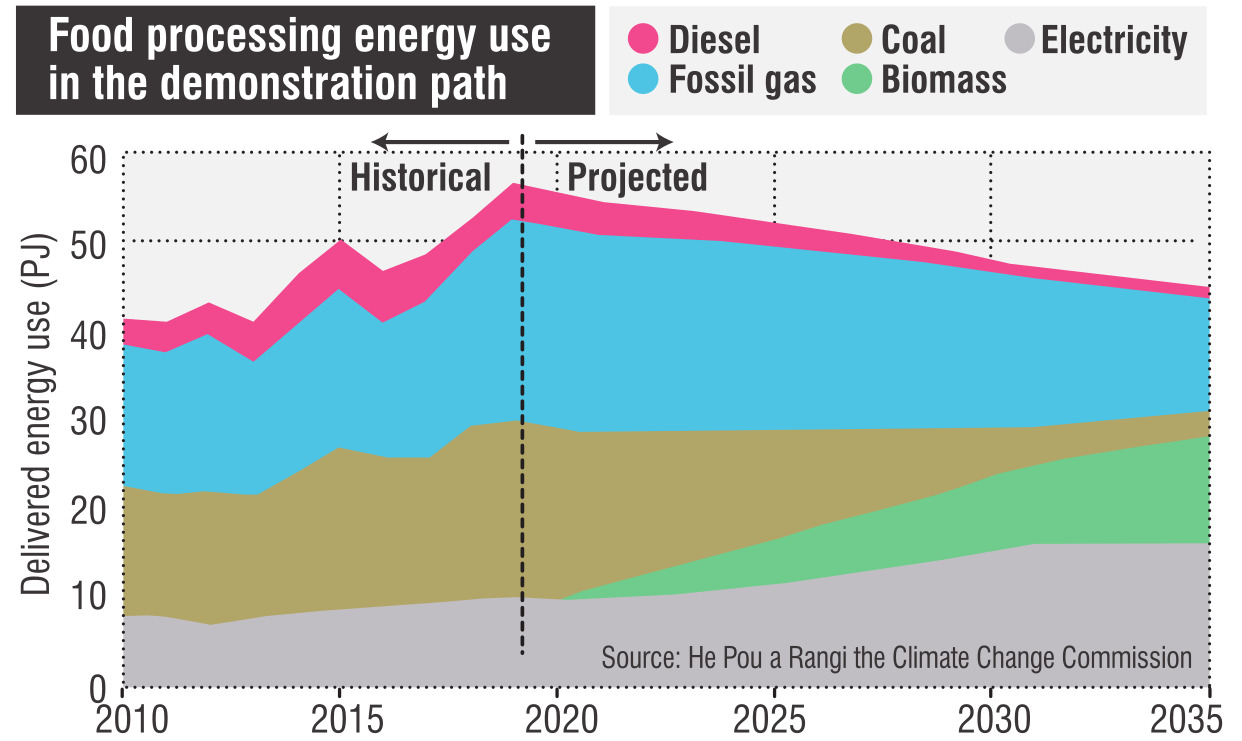

So, the graph he is examining so closely holds vital information. It illustrates the speed with which the commission believes we should abandon coal, the dirtiest of fossil fuels, as a source of energy. But the smear of dun brown, representing coal, narrows without terminating. It means that, according to the commission, we’ll be burning coal beyond 2035.

Jana Al Thea, a friend of Liam’s and a fellow climate activist, looks at the numbers and sees another truth. She is 16 and there are almost as many years again until 2035. She can expect the coal to burn for another lifetime, at least.

Jana and Liam and fellow activists Pepa Cloughley and Niamh Dillingham have gathered to go through the commission’s report. It is not a small undertaking: Inaia tonu nei stretches to more than 400 pages.

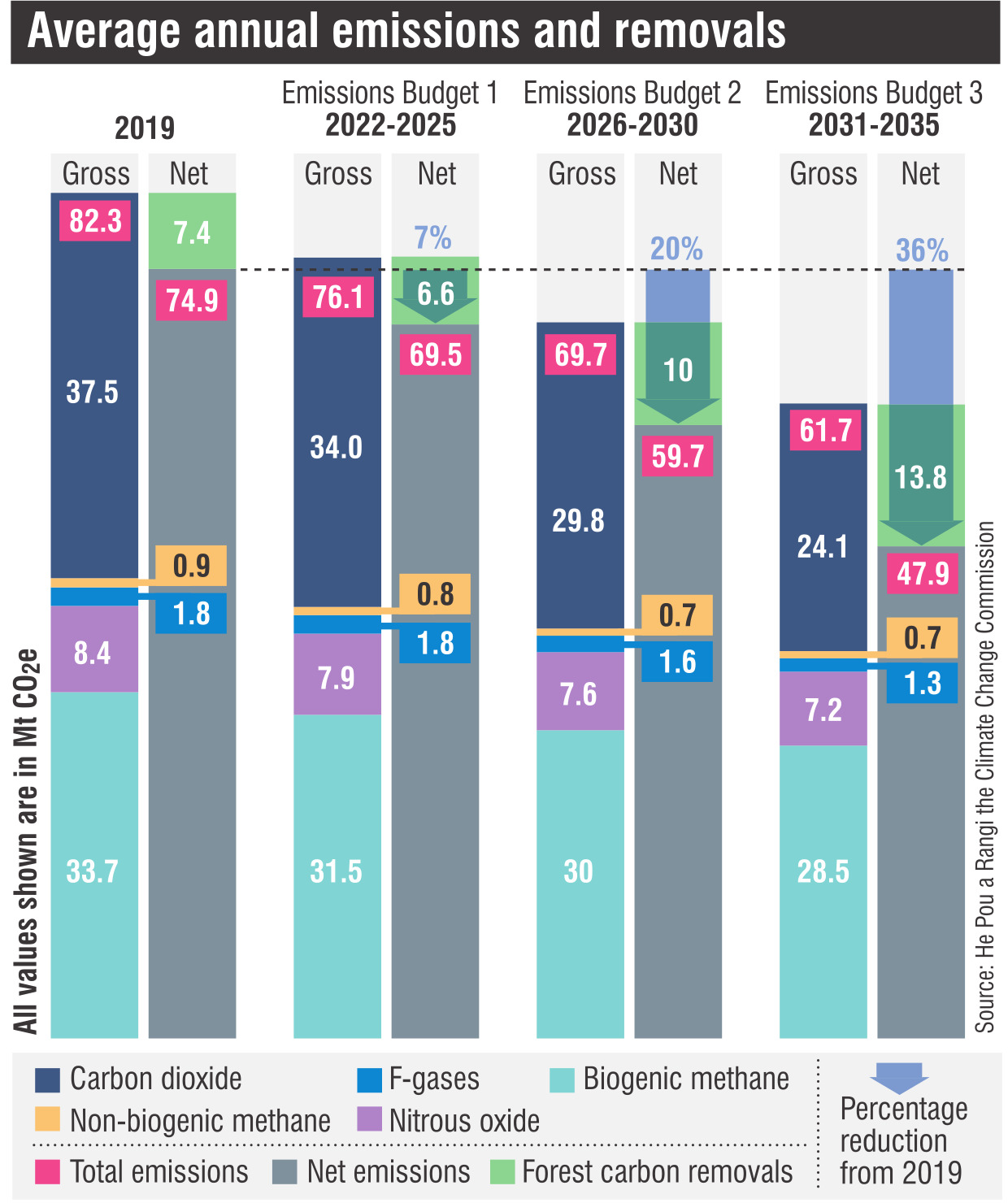

At its heart are three five-year carbon budgets, the first taking us through to 2025, the third ending in 2035.

For each of these the commission has suggested a target for reducing gross greenhouse gas emissions, and further reducing our net emissions by "carbon removals", mainly by planting trees.

Pepa heads off any sense of optimism there might be about that.

"I don’t think that politicians have an incentive to really create any meaningful change," she says.

She’s heard too many empty words.

This is the School Strike 4 Climate generation, the Extinction Rebellion generation, the Gen Zero generation. Climate change has been urgent and pressing their entire lives, and for precisely none of that time has the rhetoric around addressing the issue, from the world’s leaders, been matched by action.

They know what they are looking for and zero in on the report’s carbon budgets, particularly the first one through to 2025.

"Because of the way they have set it up, if you mess up initially, you are just creating more and more problems that will accumulate, will grow and will build on top of one another," Jana says.

There’s a brightness about Jana, as too with the others — maybe with Liam the weight of it all is more apparent, it has worn further through the buffer of his patience. But Jana is engaging with the topic with that newly generated energy of the young intellect. The challenge is fuel to her fire.

It’s a lot though. A lot to contend with and she admits to the toll.

"I feel a huge spiritual fissure forming in terms of my faith in humanity. It is not just that we are facing this huge problem and nothing is happening, it is why is it not happening? And it is these fundamental human flaws of greed ... and ownership and in taking without guarding and giving."

The commission has recommended an average 7% reduction in CO2e emissions through to 2025, that first budget period, but expects a lesser cut will be achieved in the first year.

It seems to back up Jana’s misgivings — from the end of next year we could already be behind the eight-ball.

Indeed, Liam is worried the commission’s report might be read by the Government as license to tinker, fidget around the edges of the issues.

Jana highlights a paragraph in the report that gets a wry chuckle. It’s about the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), a central part of the emission reduction machinery available to the Government.

It reads: "Improve the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme so that it provides stronger market incentives to drive low-emission choices."

And the commission is indeed recommending change to the ETS, including significant hikes in the price of a New Zealand unit.

However, there’s little confidence in the room at this the 11th hour in "market signals". For our four young activists the tide has well and truly gone out on the cult-like faith in markets of recent decades.

Another paragraph in the report catches their eye: "The demonstration path assumes that by 2030 coal use in commercial and public buildings will be largely eliminated. The Government announcement in 2020 that all coal boilers in public sector buildings will be phased out is a step towards this."

It looks like good news but the word that jumps out at them is "largely".

"Largely" looks like a slippery sort of term to them, an escape clause.

"What we need are dates when things are going to be completely banned," Pepa says.

There does seem to be an element of intergenerational unease. Boomers are well represented on the commission.

For Zoomers Liam, Jana, Pepa and Niamh, the climate is central. They can not remember a time when it was not pressing and struggle to understand the weight the commission gives to other considerations.

Niamh remembers the first time she heard discussion about ocean acidification, that other carbon pollution-driven disaster in the making. She says she knew immediately it was important. It doesn’t even get a mention in the report, though oceans as carbon sinks do.

"A lot of people who are older than us speak about a moment they realised the scale of the issue," Liam says.

Commission chair Prof Rod Carr has certainly done so. For him that moment was quite recent.

"But for a lot of people of our generation, we are kind of born into survival mode about this."

"Can I tell a Rod Carr anecdote?" Jana asks.

She attended a conference where he spoke about the commission’s work.

Afterwards, Jana hung around to talk to him.

"And I asked him about younger generations having to do more of the work. ‘What about that pressure that you are putting on the next generation, the generation after that, all these people who are younger than you to do more and fill the gaps that you have left?’."

His response, Jana says, was to recommend she lobby for free public transport for young people. As far as she is concerned, it was hardly an answer at all.

"I am not even looking for a comforting answer but I get nothing."

But Jana doesn’t want this to be about generations and age. She’s too familiar with the charge of naivete to want to go there.

She’s happy to make arguments based on the report itself and comfortable in the territory.

After all, this is a process over which her generation can claim considerable ownership.

The activist group Gen Zero drafted and promoted the Zero Carbon Act that led to the establishment of the commission and its five-year carbon budget approach. Theirs is a view that fundamental change is required in the systems that underpin our society, the systems that lead to pollution and waste.

It’s a sophisticated approach that includes notions of a just transition and sees an opportunity to address long-term inequities while dialling back the CO2.

Given that, the Gen Zero prescription was for an Act that backed action.

Liam says there are elements of the commission’s report that can still be read that way, for example, its contention that we already have the tools we need to cut emissions.

What’s required is the political spine to apply those tools as if we were at war, he says — though uncomfortable with the analogy.

"There have been situations in the past — think World War 1 and World War 2 — where countries, including New Zealand have pretty much dropped everything for a specific cause.

"I think that’s what we need to do again, that is the level of focus."

Standing on the railway tracks by the Dunedin station was about disrupting business as usual in order that priorities were altered fundamentally, he says.

The thinking is condensed in the activist slogan "System change, not climate change".

It is there in the commission’s report if you look hard enough.

A chapter on policy direction reads: "Creating political processes and institutions that support wider technological, behavioural and systems change will be critical".

It’s a bit policy-speak, but maybe a little closer to the mark. However, in the context of the wider report it can also look a bit token.

One commentator has characterised the report as meek. Other leading campaign organisations Coal Action Network Aotearoa and Greenpeace have both been critical of what they regard as weak targets on coal and methane respectively.

So, Liam, Jana, Pepa and Niamh are not alone.

Liam has moved on to another graph in the report. It’s a bar graph this time, tall thin chimney stacks of emissions marching across the page; carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, biogenic methane and the rest.

He’s not impressed. Again there’s some good news left to right, but Liam doesn’t like the reliance on tree planting the graph suggests — the commission itself has said that approach is kicking the can down the road.

Maintaining and increasing carbon removals, through forestry plantings, will be resource intensive and rely heavily on the efficacy of the ETS, he says.

"It is less about actually changing they way the system works, changing industry and the burning of fossil fuels and more about these band-aid fixes afterwards," he says.

The exasperation is raw.

All of this is just the domestic picture, the puzzle of how to meet the net-zero 2050 goal in the Zero Carbon Act.

Beyond that there is the international situation, the Paris Agreement, the United Nations Conference of the Parties in Glasgow later in the year and that red line of 1.5degC of warming.

The science says we must not cross it. Beyond is chaos and suffering.

Our country’s contribution to that effort, our Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), is well short of where it needs to be, at a 30% reduction on 2005 emissions. The commission says our share needs to be "much more than 36%". However, its solution to increasing our ambition is to pay people in other countries to reduce their emissions, which can then be counted as part of our effort.

"I find it really sad," Jana says. "They do have some really good stuff in the report, some good sentiments about how we need to do large change, the tools are already available and things like that — but when it comes down to putting the numbers in, they basically say, New Zealand can not meet our obligations to reach that 1.5degC target. I think that is really disappointing."

Given New Zealand is a developed country, it should be possible for us to do a lot more, a lot more quickly than many other places, Jana says.

"Beyond the implementation of [the budgets], if this advice were followed by the whole world, we still wouldn’t meet that 1.5degC target," Liam says. "We would still devastate our planet."

Jana sums up the situation. It’s not yet time for the activists to hang up their banners, she says.

As far as she is concerned, as far as Liam, Pepa and Niamh are concerned, the adults are not yet taking this seriously.

Comments

Adults with vested interests, to be precise.

These eco warriors deserve our support at least until governments start treating the threat of climate change like the emergency it really is.

Climate change tipping points are upon us, draft U.N. report warns: 'The worst is yet to come'

A draft report by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a copy of which was obtained by Agence France-Presse, states that mankind may have already missed its opportunity to keep the climate from passing a series of thresholds that will further spur the warming of the planet.

“Life on Earth can recover from a drastic climate shift by evolving into new species and creating new ecosystems,” the report says. “Humans cannot.”

“The worst is yet to come, affecting our children’s and grandchildren’s lives much more than our own,” the report says.

“We need transformational change operating on processes and behaviors at all levels: individual, communities, business, institutions and governments,” it says, adding, “We must redefine our way of life and consumption.”