Everybody knows the sun is the source of life on Earth. We learned about the food web in primary school: plants make sunshine into leaves, bugs eat the leaves, birds eat the bugs and that’s how we get chicken nuggets on the menu. But there are remote corners of the ocean where the sun never shines, and yet life is resplendent.

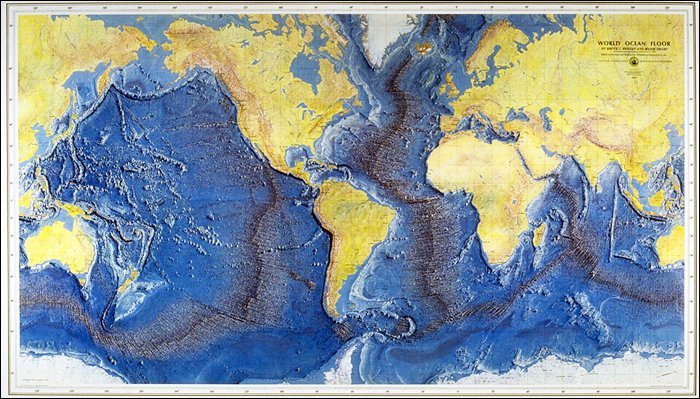

Until 1974, most maps showed the sea as a single featureless blue blanket, where there could be anything underneath — but probably there was nothing. World War 2 technology allowed peacetime mapping of the sea floor, and throughout the 1950s and ’60s it became increasingly clear that the sea floor was neither flat nor featureless. Oceanographic cartographers Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen painstakingly produced the most important map in the history of marine science: the 1977 World Ocean Floor Map.

Just look at it! Undersea mountain chains, remarkably straight furrows, dotted volcanos, spectacular faults. This map was the fuel that fed further scientific exploration of the sea floor, and scientists continue to try to answer the questions that this remarkable map asks.

And yet there is life. In the deepest of deeps (more than 10km down), most organisms have no air pockets — they are gelatinous and slow-moving. A little less deep, there are bioluminescent fish and squid which create their own light to lure in prey; most deep-sea predators have huge eyes. Here the food web is based mainly on "marine snow", or the occasional richness of a dead whale, that falls from above.

Even more astonishing are the "vent faunas" — ecosystems based not on sunshine, but on chemicals from inside the earth. Instead of plants using sunshine to make leaves, bacteria at deep-sea vents convert chemicals into nutrients. A special and unusual food web has developed around them. Tiny bugs dine on the bacterial mats, and are in turn consumed by snails, clams, octopuses, crabs and shrimp, even some eels. Most of them are white or transparent, in their dark chemical world.

The most spectacular vent critters are the giant tubeworms. Up to 2m tall, they have no mouth or digestive system. Instead, they host millions of bacteria in their tissues. The worms collect chemicals from seawater for the bacteria, and the bacteria fix carbon for the worms — a process called chemoautotrophic bacterial endosymbiosis! This method of getting energy must work, because giant tubeworms are among the fastest-growing creatures on Earth — a metre in only 18 months. They can only survive while the vent is active, so they live fast and reproduce a lot — generating thousands of larvae that can swim around for a month or more searching for another life-giving vent.

Vent faunas are very old — they appear to have remained relatively unchanged since the times of the dinosaurs. Mass extinctions on the surface of Earth have left them unscathed. In 2017 scientists reported the oldest evidence of life on Earth, a fossil micro-organism from a long-gone hydrothermal vent 4.2billion years ago, fairly soon after Earth’s oceans were formed.

In fact, vents in the ocean deeps may offer the right conditions for life to begin. Life needs carbon and water, but also amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. Scientists have been able to generate "proto-cells" in warm, chemical-rich seawater such as occurs at deep-water vents.

Those chemical-rich waters produce valuable and useful minerals such as copper, zinc, manganese and cobalt. Deep-sea mining has been called "the new global gold rush". It is challenging and difficult: imagine extracting mineral-rich deposits from depths of 1500m to 4000m using hydraulic pumps or lines of buckets from a heaving ship. While collection of bits of the seafloor is certainly disastrous for local abyssal life and ecosystems, it may be the resulting sediment plume that does the most damage. Choking clouds of mud particles follow deep-sea mining ships, affecting not only the bottom where they settle, but also plankton in the water column. Greenpeace and others have consequently called for sea-floor mining to be banned worldwide.

Especially now in springtime, we look up to the sun as the source of life. It feeds us all. But our oldest ancestors, the beginning of life itself, may have begun in the deepest dark corners of the sea. We can’t see or visit the deep-sea vents, but we know they are there, and we can protect them.

- Abby Smith is a professor of marine science at the University of Otago.