A similar confusion and revelation can occur in biology with what are known as sibling (or, more accurately, cryptic) species. Taxonomists, the authority figures of biological classification, at first fail to notice the differences, just like the duke and countess in Shakespeare’s tale.

Sibling/cryptic species are species that look very similar to each other, but are truly separate, in that they only breed with others of their own species.

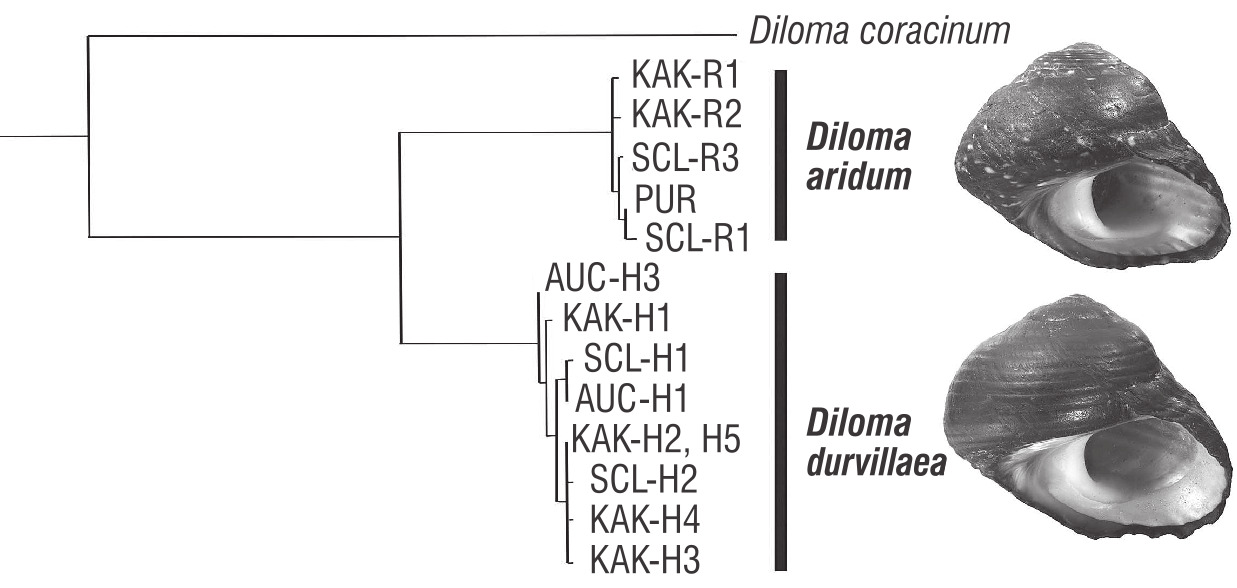

Increasingly today, the distinctive nature of sibling species is often exposed by genetic studies. If just one species were present, different individuals would be genetically close. But the genetic variation of two sibling species will fall into two quite separate groups. And, as in Twelfth Night, after the big reveal, the differences between the siblings may become startlingly obvious.

On a field trip to Kaka Point in South Otago, my colleagues and I found what we took to be Diloma aridum in a new habitat: on and under the holdfasts of rimurapa, the giant bullkelp (Durvillaea antarctica) at and below the low-tide mark.

Unlike true plants, which anchor themselves into the ground with roots through which they absorb water and nutrients, many marine seaweeds simply glue themselves, using a holdfast, to their rocky substrate. No nutrients, let alone water, are delivered via the holdfast; its sole purpose is to keep the alga in one place.

The holdfasts of rimurapa are particularly interesting, nevertheless, in that they are home to a host of different small animals: limpets, chitons, snails, worms, crustacea, bryozoans and more. These small creatures sometimes bore tunnels into the holdfasts, in which a wide variety of other organisms can shelter. Indeed, some of the holdfast species seem to be confined to this specialised habitat.

Moreover, when we looked more carefully at the shells of our new species, we found we could easily distinguish them from Diloma aridum. The differences were obvious once we knew to look. The shell of our new species (see the figure) has a rounder profile than D. aridum, with obvious ribs spiralling around the outside of the shell. It is a dull jet black and mostly lacks the pale-yellow flecks that are common on D. aridum.

As far as we know, these sibling species do live happily ever after. They can both be found at the same locations (such as Kaka Point and St Clair), although they probably never meet, since they occur at different levels on the shore. D. durvillaea also has a less expansive range, living, so far as we know, only on Maungahuka/Auckland Islands and the eastern and southern coasts of Te Waipounamu/the South Island. It is absent from Rckohu/Chatham and Te Ika-a-Māui/the North Island.

The Twelfth Night scenario is surprisingly frequent in biological research in Aotearoa New Zealand. We are, it seems, still in an age of discovery when it comes to our biological taonga. Amazingly, at the same time in the same place, this same group of researchers also found a cryptic species of rimurapa/bullkelp. But that is another story with perhaps a different Shakespeare play to reference!

Hamish G. Spencer is sesquicentennial distinguished Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago