Swift used his pet name for her, Vanessa (made up from the Van in her surname and a diminutive of her first name, Essa), and, in the poem, likened her to a classical nymph, shot with one of Cupid’s darts. We know all of this because his poem Cadenus and Vanessa was published after Vanhomrigh’s death, as she had requested. Vanhomrigh apparently never got over Swift’s rejection and the publicity was part of her posthumous revenge.

This sorry tale has had two longer-term consequences. First, it has given us the girl’s name Vanessa.

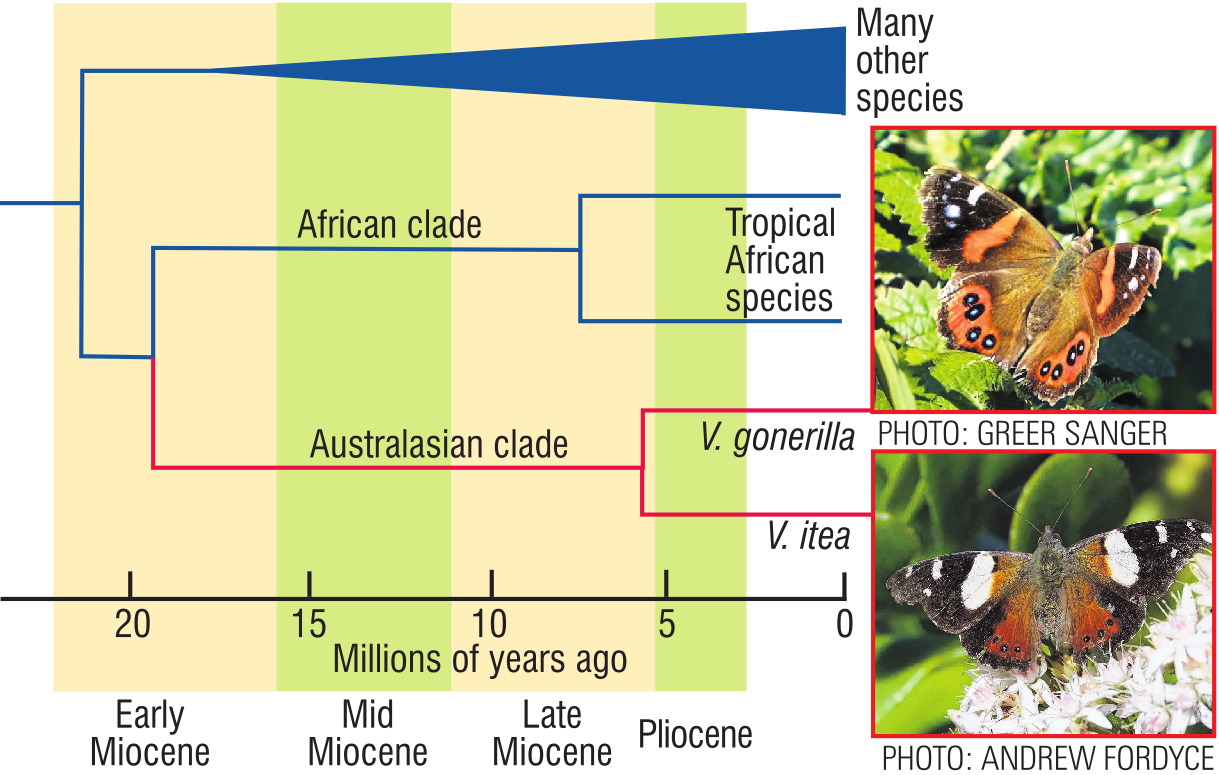

Today the genus Vanessa comprises some 22 species worldwide, of which perhaps the most stunningly patterned is our kahukura or New Zealand red admiral, known scientifically as Vanessa gonerilla. Not to be confused with the widespread northern hemisphere butterfly known as the red admiral (Vanessa atalanta), our species is endemic, found only in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The closest relative of our red admiral is the kahukōwhai or the yellow admiral, Vanessa itea, which occurs in Australia as well as here. It is thought to be a fairly recent arrival in the country, with records dating back only to the mid-1800s, only spreading to the Otago region by about 1960.

A third species in the genus, pepe para hua or the Australian Painted Lady, Vanessa kershawi, strays here, sometimes in large numbers, but seemingly cannot overwinter successfully.

Kahukura caterpillars feed on nettles, preferring our native species, especially ongaonga or tree nettle, Urtica ferox. Nettles provide protection for the young kahukura, which sometimes sew leaves together as a shelter. By contrast, kahukōwhai larvae seem restricted to introduced nettles, in keeping with the hypothesis about its recent Australian origin.

Eggs hatch 8-9 days after laying, and the larvae feed for a further 4-6 weeks, growing to about 4cm before pupating. Inside the pupae, the miraculous metamorphosis from caterpillar to butterfly takes up to 3 weeks in summer, a little longer as temperatures drop in autumn.

Red and yellow admirals overwinter as adults, which can sometimes be seen flying or sunning themselves on warmer days. They can become rather bedraggled, however, showing extensive wing damage as they age.

Genetic analyses show that the ancestor of our red and yellow admirals separated from the other members of the genus about 20 million years ago, in the early Miocene; the two species split from each other in the late Miocene, about 5.5 million years ago (see diagram).

These dates suggest that the ancestors of our red admiral were blown across the Tasman Sea and subsequently evolved here, adapting to our native nettles over the past 5 million years. At the same time, the yellow admiral evolved in Australia, before establishing in Aotearoa in the past 150 years or so. Any stray yellow admirals that arrived before then presumably could not find suitable host plants.

Interestingly, the Chatham Islands population of the red admiral appears slightly different, more orange and with more rounded hindwings. It has been described as a separate subspecies, V. gonerilla ida, and could have arisen from a small number of founders arriving there after a storm. Genetic work to test this hypothesis is under way.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that, sadly, our endemic kahukura is declining in numbers. The introduction of two small wasp species that parasitize the pupae is probably partly to blame. But the spraying and clearing out of our native nettles does not help either. So, if you want to see more of this beautiful taonga in your garden, don’t spray and don’t pull out the nettles. Indeed, you could even plant native nettles (in areas away from children). And if you like flowers, perhaps plant some Buddleja.

Hamish G. Spencer is Sesquicentennial Distinguished Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago