Department of geology head Prof James White was part of an international team of researchers studying the 2012 eruption of Havre volcano.

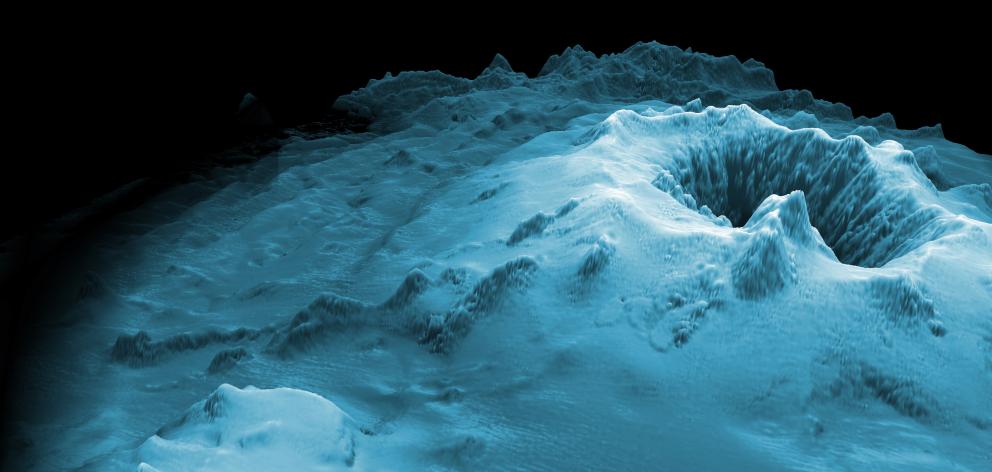

The two-year study involved using submersibles, including a remotely operated vehicle and an autonomous underwater vehicle, to map, observe and collect samples from the volcano.

The team’s findings have just been published online in Science Advances.

In 2012, a gigantic pumice raft was detected floating in the ocean near New Zealand, indicating a submarine volcanic eruption had occurred.

The raft was 400sq km on day one, and its spread was tracked to more than a half million sq km four months later.

Lead author Dr Rebecca Carey, of the University of Tasmania, said the pre-eruption map of Havre volcano allowed the team to know what and where the new eruption emissions were on the submarine landscape.

There are conceptual theories about how deep ocean volcanic eruptions should be suppressed by the pressure of overlying water.

This was the first eruption of silica-rich magma where scientists could test if the theories were correct.

"We were able to demonstrate that the eruption was very complex, involving more than 14 aligned vents that represent a massive rupture of the volcanic edifice.

"We were also able to demonstrate that 80% of the volume of the pumice was delivered to the pumice raft and efficiently dispersed into the Pacific Ocean."

The raft proved one of the most exciting things for Prof White, as it was not deposited anywhere near the volcano.

"If we looked at the geological record of this eruption, we would have no evidence at all for the pumice raft, which was the main product of the eruption and the only one seen by satellite and encountered by ships.

"To a geologist, this raises fascinating problems for interpreting the geological record that has been our main way of learning about submarine volcanism," he said.

The eruption emissions found on the seafloor included car-sized blocks of pumice and a thin, fine, widely dispersed layer of volcanic ash.

"This is very different from what we see deposited on land from ash-bearing eruption clouds. It was also almost entirely different from what we expected — the ocean floor remains truly a frontier realm, where people can discover new things simply by going there.

"This allows Earth to present us with important new research questions, questions about things we didn’t even know there was a need to explain."

Prof White is currently conducting a Marsden-funded project using samples taken during the research cruise.

The project is focused on understanding the volcanic ash from the eruption and what it indicates about its style.

"With our partners in Germany, the samples are re-melted in small crucibles then fragmented in different ways, in water and in air, to produce different types of ash grains, while measuring their formative processes (pressure, heat, energy)."

Along with University of Otago PhD student Arran Murch, Prof White will compare the laboratory ash grains with the natural ash grains to determine the dominant processes in the eruption, and to estimate the heat and energy involved in producing the seafloor ash deposit.