- Where to get vaccinated in Otago, Southland this Super Saturday

- Dunedin still leading the way with vaccinations

The clarion call for vaccination to reach as many people as possible may well be annoying by now for those who would rather not choose that method of defence against Covid-19.

A push to achieve a vaccination rate of at least 90% of the eligible population will hit a crescendo tomorrow.

Some of the target audience will reach for earmuffs. Others may be on the fence, uncertain of the science or wondering what the case is to get jabbed, imminently.

The Otago Daily Times approached three experts for their take on questions that people who could be hesitant about getting vaccinated may have.

- Vax support born of polio ordeal

- Immunocompromised front-line healthcare worker explains why vaccination is crucial

- Opinion: The chance to care for each other helps in many ways

Prof James Ussher is an immunologist at the University of Otago.

Time is running out for people to get vaccinated before SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, circulates more widely in the community, he says.

Globally, there have been more than 238million cases and more than 4.85million deaths from Covid-19.

Prof Ussher says pressure on people so far unvaccinated is necessary.

Prof Peter Crampton is a public health specialist who works in Kohatu, the Centre for Hauora Maori at the Otago Medical School. He is also a member of the Southern District Health Board.

Prof Crampton says it is important for people to feel comfortable with decisions about vaccination, but there is a widespread sense of urgency because the highly transmissible Delta variant of Covid-19 presents a threat both to Auckland and the rest of New Zealand.

Dunedin city councillor Dr Jim O’Malley is a scientist who used to work for Pfizer, where he was a senior researcher in drug discovery.

"If there had been a full outbreak of Covid-19 last year before the vaccines existed, the intensive care wards would have been overwhelmed and we would probably have had around 250 deaths in Dunedin alone," he says.

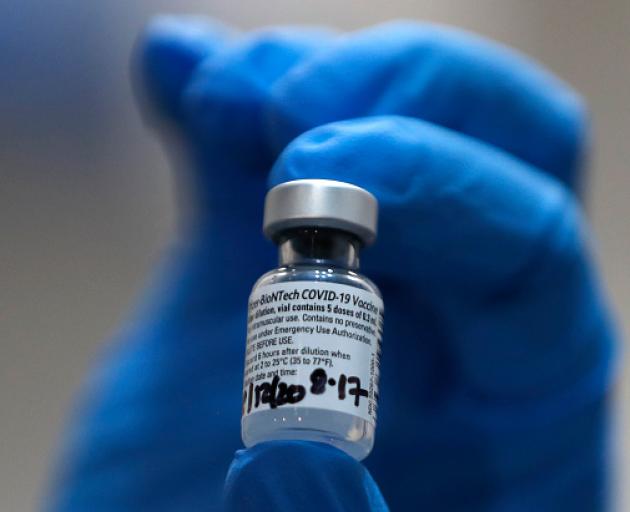

What is in the vaccine?

The way Environmental Protection Authority scientist Dr Tim Strabala explains it, the vaccine is made up of engineered messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) molecules encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle capsule.

The capsule is the vehicle that gets the vaccine to cells and the mRNA then does its work.

It has the genetic code to make the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

When the protein exits cells, the immune system recognises it as foreign and responds.

The next time the immune system sees the spike protein (if we are exposed to the actual virus), it is ready for it, Dr Strabala says.

Messenger RNA has been described as the active ingredient and the inactive ingredients are four salts, four lipids and sucrose.

The Ministry of Health calls the lipid nanoparticle a stabilised fat bubble that protects and carries the mRNA into cells. Salts maintain acidity balance of the vaccine. Sucrose, or sugar, protects the vaccine while it is in storage.

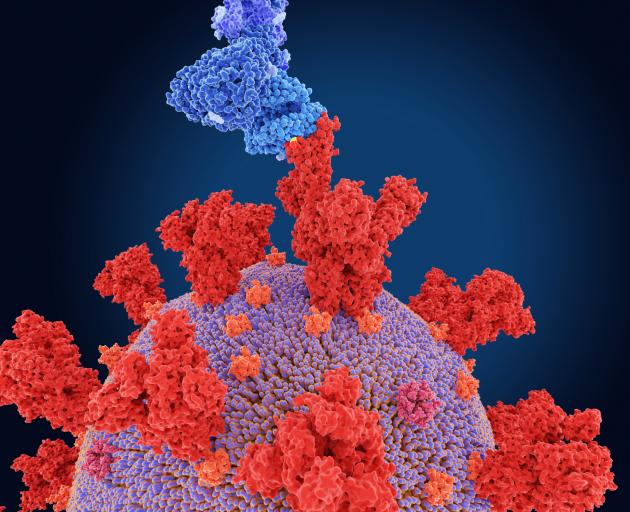

Are we in the realm of experimental gene therapy? Is the spike protein a toxin?

Research on RNA vaccines dates back to the early 1990s, Prof Ussher says.

"RNA is a temporary messenger in the cell, lasting hours to days, leading to short-term production of the spike protein.

"RNA does not enter the nucleus and even if it could, it couldn’t alter our genes.

"Therefore, it is totally incorrect to call it gene therapy, which requires alteration of DNA."

Dr O’Malley says the use of mRNAs to treat diseases is emerging all through medicine.

At no time does a modified RNA interact with a cell’s DNA.

The spike protein is the part of the virus that allows it to attach to a cell and inject its RNA into the cell, Dr O’Malley says.

"A spike protein all by itself has no biological activity, so is not a toxin."

By targeting the spike protein, any antibodies generated are targeted to the part of the virus that makes it infectious.

Is it safe?

Prof Crampton says adverse reactions are well within the normal range that would be expected with a vaccine.

Myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) and pericarditis (inflammation of the lining outside the heart) have occurred in some people who have received the vaccine.

Dr O’Malley points out they are much more rare than the known effects of getting Covid.

Prof Ussher says the risk of getting myocarditis with the vaccine is much less than getting it from natural infection.

"The vast majority of myocarditis and pericarditis following the vaccine are mild or moderate and settle with anti-inflammatories."

Side-effects that have been reported with the vaccine include severe allergic reactions, rashes, tiredness, headaches, arm pain and fever. They may last for a few days.

What about long-term effects?

"Because the vaccine has been used for only a relatively short period of time, it is not possible to determine with 100% certainty if there are any long-term effects," Prof Crampton says.

Covid-19 vaccines have been in widespread use since December last year — Prof Ussher says few adverse effects have been identified and they are rare.

"Given the number of doses administered to date around the world and the extremely close monitoring, it is increasingly unlikely that additional adverse effects from the vaccine will be identified."

Was the vaccine approvals process rushed?

Prof Crampton says Pfizer’s vaccine development followed the usual process, but with efficiencies resulting from running several aspects in parallel, rather than one after the other.

"The clinical trials part of the process was carried out with the same rigour as usual, but without assessment over the long term because of the need for the rapid rollout of the vaccine."

Prof Ussher lists a series of reasons explaining why the vaccine could be produced and approved so quickly.

They include that lack of money, usually an obstacle to quick progress, was not a factor this time.

Vaccine development efforts through to clinical trials had already taken place for the likes of SARS and MERS and this helped to make a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2.

There had been research and investment over many years into vaccine platform technologies that could be rapidly adapted to SARS-CoV-2.

Trials were of the highest quality, Prof Ussher says.

"Over 46,000 people were involved in the clinical trials for the Pfizer vaccine.

"There has been extremely close monitoring of the vaccines since authorisation."

Medsafe gave provisional approval for use of the Pfizer vaccine in New Zealand, with conditions, on February 3 this year. This means it has been formally approved after a thorough assessment, but Pfizer must give Medsafe ongoing data and reporting to show it meets international standards.

Dr O’Malley says safety was never compromised, but combining the last two phases of the three-phase trial saved about eight months.

During the third phase, 38,000 people were enrolled in 152 trial sites in the United States, Germany, Turkey, South Africa, Brazil and Argentina.

Half were given the vaccine three weeks apart and half had two shots of a placebo.

The effect of the vaccine was measured up to a week after the second dose, Dr O’Malley says.

The Covid-19 infection developed in 169 people in the placebo group, but in just nine people who had received the vaccine.

"This is how they came up with the 95% vaccine efficacy number."

Is it effective?

Prof Crampton sums up the benefits of vaccination:

It dramatically reduces a person’s risk of needing hospital treatment for Covid-19.

It hugely reduces the chances of dying from Covid-19.

It significantly reduces the risk of passing Covid-19 on to someone else.

There is growing evidence vaccination reduces the chances of long Covid, the form of the disease that produces lasting symptoms.

The vaccine’s effectiveness declines with time. Has its worth been hyped or exaggerated?

"The human body ‘forgets’ coronaviruses, which means that after an infection or a vaccination the immune response drops off over time," Dr O’Malley says.

"It also means that if you get Covid once, you can get it again."

Booster shots will be needed, he says.

"Whether to boost at six months or eight months is being considered in countries that started vaccinating earlier than us.

"I imagine the big companies will be trialling new variations of their vaccines to account for Covid-19 mutations and these will be rolled out in the boosters."

Prof Ussher says a decline in effectiveness against symptomatic infection with time due to waning immunity has been observed — from 95% to about 50% effectiveness.

However, the Pfizer vaccine remains highly effective against severe disease leading to hospital admission or death.

"While someone who has been vaccinated may still develop a cold, they are 10 times less likely to need hospitalisation or die than a non-vaccinated person."

Prof Crampton says the experience in the United Kingdom demonstrates the effectiveness of vaccination in reducing the chances of hospital admission and death.

Some people in rural areas may consider they rarely come across many people, so the pandemic is unlikely to reach them. How would you respond?

Dr O’Malley: "The virus has got to the most remote regions on Earth.

"It will make its way into the countryside."

Prof Crampton: "Given that we live in a highly mobile society, it won’t take long for Covid to spread into all communities.

"Even if you believe the chances of coming into contact with Covid are slim, it is such a highly infectious virus it is wise to protect yourself, your family and your community by getting vaccinated."

Prof Ussher: "While it may take longer for the virus to reach rural areas, it will eventually get there.

"This virus will be circulating around the world now indefinitely.

"Of note, people living rurally are also more remote from healthcare services should they need them if they get seriously unwell, underlining the importance of getting vaccinated."

Who is most vulnerable?

Dr O’Malley says a person who refuses to get vaccinated increases the risk for everyone around them.

Prof Ussher says data suggests Maori are at increased risk of needing hospital admission.

Groups most vulnerable to the disease include older adults and those with other conditions such as heart disease, lung disease, hypertension and obesity.

Prof Crampton adds Pacific people to the list.

"It is absolutely essential that clinics and vaccination services reach out to all communities and whanau so that everyone has the opportunity to be vaccinated."