The first thing Jonathan Haidt asks when we sit down is my age. I know what he’s thinking: he wants to place me, technologically. Am I a member of the "anxious generation", the term he has coined for the young people who he believes have been psychologically harmed by social media and smartphone use at a tender age? Or am I more likely to be one of the concerned parents who are the primary audience for his book? At 33 (the oldest of his anxious generation are currently 28) and child-free, I don’t quite fit into either camp.

I also don’t quite align with either of the two sides that have emerged in response to Haidt’s argument. While his book, The Anxious Generation, has undoubtedly made a splash, sparking a heated public debate about adolescent technology use, the science underpinning his thesis has also met criticism from other researchers in his field.

So is the book’s popularity because Haidt has correctly diagnosed an urgent social ailment? Or because he’s spinning parents a story that they desperately want to believe: that there is a simple solution to this complex problem?

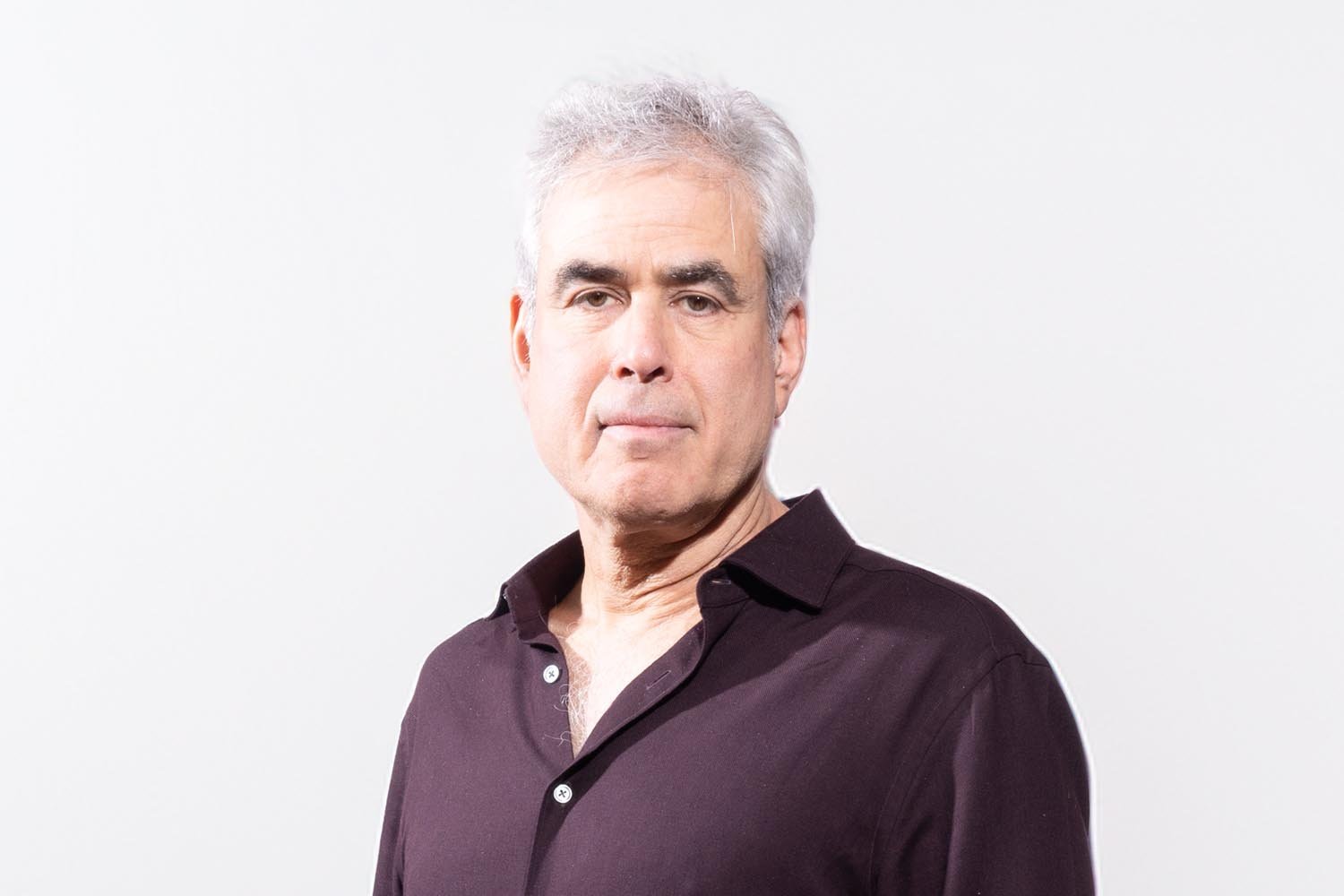

At 61, with neat grey hair and thick, dark eyebrows, Haidt perfectly embodies the role of affable, credible academic. He currently teaches social psychology at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

The starting point for The Anxious Generation is the crisis in young people’s mental health — in his native US and across much of the West. The proportion of children and young people in the United Kingdom with mental disorders rose from 12% to 20% between 2017 and 2023. The question is: why, and what can we do about it?

Haidt says the increase in anxiety and depression among young people is directly caused by their use of smartphones and social media. "Gen Z became the first generation in history to go through puberty with a portal in their pockets that called them away from the people nearby and into an alternative universe that was exciting, addictive, unstable, and ... unsuitable for children and adolescents," he writes.

He specifically identifies the period between 2010 and 2015 as a time when smartphones and social media were updated to include addictive and harmful features, corresponding with a marked increase in anxiety and depression for children coming of age during this period. Exposure to these technologies during puberty causes long-term effects on the brain, Haidt argues. He calls this "the Great Rewiring".

Haidt outlines four ways in which young people are negatively affected by social media and smartphones: sleep deprivation, social deprivation, attention fragmentation and addiction. Since The Anxious Generation was published, he has come to believe the threat to attention is the biggest concern, both for children and adults. "My argument is that these platforms are clearly, demonstrably, harming children at an industrial scale, by their millions," he says.

He offers four simple rules to reverse the course of what he calls the "phone-based childhood". These are: no smartphones before 14; no social media before 16; phone-free schools; and more unsupervised play and childhood independence.

The suggestions seem reasonable enough. Even some of his critics agree with them. They all require group mobilisation to avoid the "collective action problem" — it’s much harder to enforce a change unless other parents are doing it too. If just one child has no smartphone or social media, they will feel excluded from their peers. As Haidt writes: "Few parents want their preteens to disappear into a phone, but a vision of their child being a social outcast is even more distressing."

In the UK, there was already momentum to this discussion before Haidt’s book. The 2023 Online Safety Act puts more responsibility on tech platforms to ensure they are safe for users, especially children. It is one reason that Haidt calls the UK "the leading country on protecting kids online".

Some critics claim Haidt is exacerbating a moral panic. Just as previous generations of adults claimed television, hip-hop, video games and comic books were corrupting the youth, they say Haidt is the latest avatar of the old guard inventing horror stories around new culture and technology they don’t understand. Despite his avuncular demeanour and his pleasant habit of murmuring agreement with me while I speak, Haidt has arrived ready to prove every point in his book.

"There certainly have been moral panics," he says, "and whatever technology the kids are using, the adults are going to be sceptical of. It’s a valid criticism as a starting hypothesis. The obligation is on me to show this time is different. And I can very easily do that."

His response to the moral panic accusation is twofold. One: he argues there has never historically been an introduction of new technology followed so directly by a precipitous global decline in youth mental health. Two: in previous generations, if you asked children how they felt about their comic books or video games, they would say they loved them, please don’t take them away. But when young people today are surveyed about social media, significant numbers regret how much they use it, find them harmful, and in some cases wish they’d never been invented.

So what is the controversy around the data? It boils down to a single, difficult question. Experts agree that mental health problems among teenagers are rising at the same time as smartphones and social media are playing increasingly ubiquitous roles in their lives. But is this mere correlation? Or is the technology causing the mental illness?

Several prominent academics have argued that Haidt’s claim of causation is an oversimplification; that there is no one simple answer to such a complex sociological problem. A particularly searing review in the academic journal Nature argued that Haidt’s central thesis "is not supported by science" and that "the bold proposal that social media is to blame might distract us from effectively responding to the real causes of the current mental-health crisis in young people". Others have argued that the research around this topic is unreliable and ambiguous, or even conducted studies that contradict Haidt’s claims.

Sonia Livingstone, a social psychologist at the London School of Economics who researches children’s lives in the digital age, says we don’t know which way the data points: are smartphones causing poor mental health in children? Or are children with poor mental health turning to smartphones for entertainment and escape? Academics have also offered alternative reasons why young people might be struggling, from the state of global politics to the economy, to the environment. Haidt raises a couple of these in his book and claims they don’t fit his timeline, but other experts are not so quick to dismiss the other theories. On his blog, Haidt has posted a series of detailed responses to his critics.

Ultimately, there’s enough doubt to concede that there is no scientific consensus around the topic. So how much public policy and parenting advice do we want to generate from unsettled science? Haidt argues it’s better to act before it’s too late. He writes: "At a certain point, we need to take action based on the most plausible theory, even if we can’t be 100% certain that we have the correct causal theory. I think that point is now."

Perhaps part of the reason that Haidt riles up members of the scientific establishment is because of how he positions himself publicly — as part scientist, part crusader. He is adept at self-promotion and has turned his book launch into a global campaign, telling me his goal is to "roll back the phone-based childhood in three years".

This campaigning approach has precedent in his career: he has launched a series of non-profits over the years. He has also written books and taught classes that lean into the idea of self-improvement, casting him as something of a lifestyle guru. He tells me he wrote a personal mission statement in 2011: "To use my research in moral psychology and the research of others to help people better understand each other and to help important social institutions work better. That’s my mission on this Earth." While this crusading image may work for getting attention and building Haidt’s personal brand, it also flattens how his argument enters the public sphere. Critiques of his work often mischaracterise his thesis as a neo-Luddite assault on all screen time, when in fact his book is quite specific about which technology is harmful to whom, even making some — if not abundant — space to discuss where the argument gets tricky or the science unclear.

Reading Haidt’s book, I couldn’t help reflecting on my own teenage years online. I had many positive experiences and made significant friends on forums and online video games at a time when I felt I didn’t fit in at school. When I was coming to terms with my sexuality aged 14, I found vital resources and community on the internet.

The Anxious Generation argues that digitally-mediated relationships are inherently less meaningful than their real-life counterparts. This is not true in my experience. Where the book does bring up the benefits that can come from virtual communities, they are briefly raised and then tossed aside. In our conversation, Haidt points out that I grew up on a different, less harmful version of the web, before social media companies deliberately employed addictive design features such as algorithmic feeds, conversation streaks and auto-playing videos to juice users for maximum engagement, and therefore maximum profit.

This is true — the internet of my formative years was a simpler one. But does that really mean young people can’t have positive experiences on today’s social media? Haidt concedes that the internet can still be a valuable resource for marginalised groups such as queer people, but he also says that these groups are disproportionately the target of online harassment and abuse. In his view, the cons outweigh the pros.

Livingstone disagrees. "Haidt puts these two sides on the scales and says the bullying outweighs the expression and finding your community, but there are some really good things here. We need to work out how to regulate big tech so that the bullying stops and the hate is not amplified."

We should try to curtail tech companies’ addictive, data-driven business models to make social media platforms better, safer places before resorting to an outright ban, she says, while noting it is very hard to mobilise politicians about children’s wellbeing when there are major dollars on the table from big tech lobbying.

There are benefits to social media too, she says.

"Children are absolutely clear that they love being in touch with their friends. They love that when something bad happens, they can get social support. When they’re stuck at home and their parents are fighting, they can go somewhere and say: ‘Bloody hell, dad’s shouting at mum again’."

Livingstone believes that we need to look at the question with a wider lens. "What do we think a good childhood looks like?" she asks. "If we don’t let children go on social media till they’re 16, what is our plan for them being in touch with their friends? Are we going to let them out after school and let them walk home by themselves and hang out at the bus stop, or are we going to report them as hoodlums and menaces?"

We live in a world where we have welcomed technology into every crevice of our work, social and leisure time. Countless services force us to create digital accounts to access them; educational technology is being rolled out across schools; AI is being inserted everywhere. "We have invested in tech across the board," Livingstone says. "It’s becoming our infrastructure. And in that context, to say ‘kids shouldn’t be anywhere near it’ — what’s the vision in terms of restricting them, and what is the vision in terms of providing something better for them?"

"We can ban smartphones," she says, "but we’re not going to make kids happy overnight." — The Observer