University of Otago palaeoecologist Dr Nic Rawlence said the "bone grab technique'' used to analyse bone fragments found in ancient middens allowed scientists to fill in the details and go beyond understanding simply the "broad picture''.

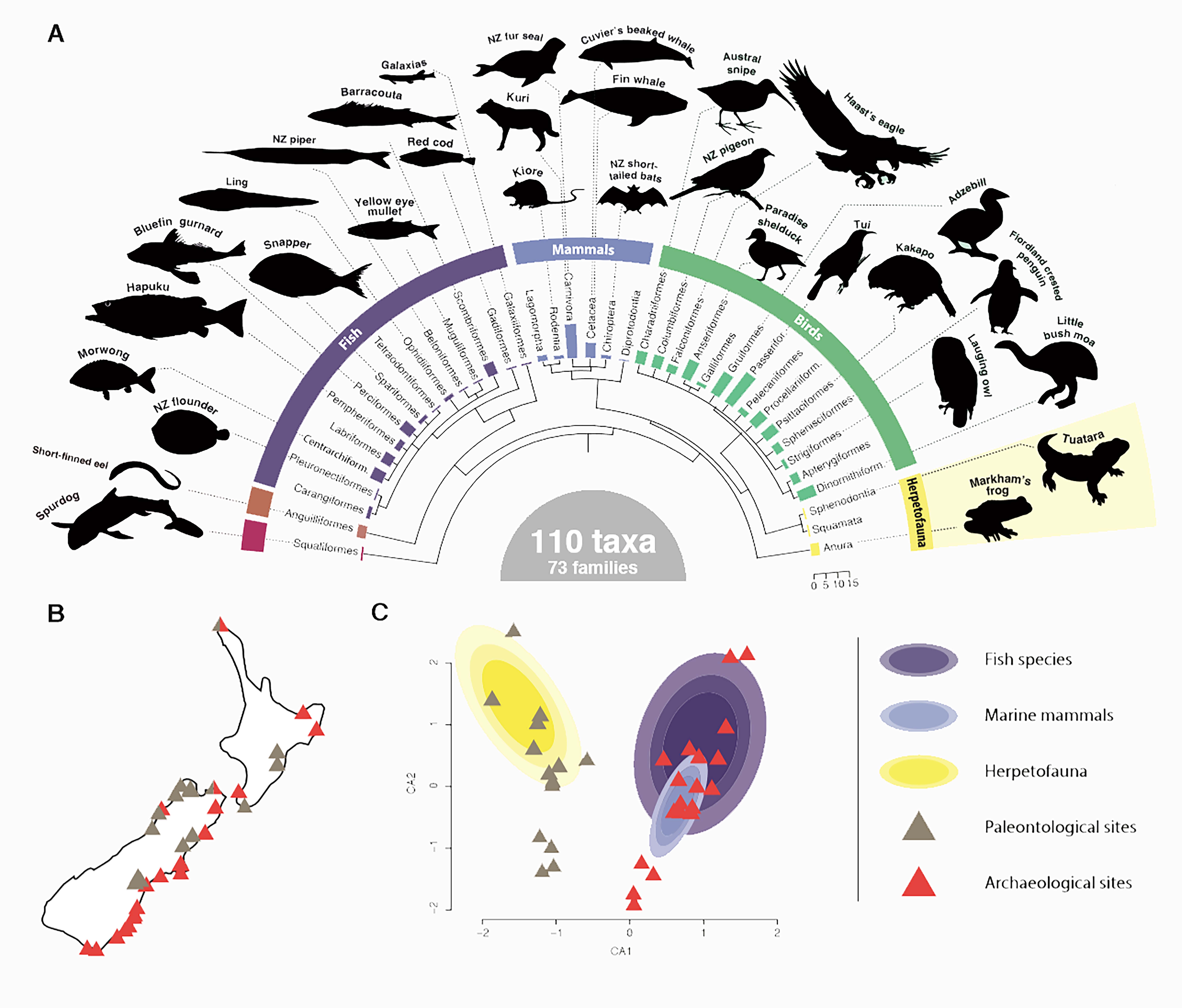

In a first-of-its-kind study, the technique was used to identify 110 species of birds, fish, reptiles, frogs and marine mammals in otherwise unidentifiable bone fragments from sites across New Zealand.

"We genetically identified over 5000 fragmentary bones, covering 20,000 years of New Zealand history - and that came from 15 fossil and 21 midden sites across the length of New Zealand,'' he said.

"We've been able to show that Maori fished locally. So, the local fish and chip shop was very important.

"We can start answering questions about seasonality and trade and human behaviour in a lot more detail.''

Dr Rawlence was among the University of Otago zoology, anthropology and archaeology, and anatomy department academics, and Canterbury Museum and Te Papa researchers who assisted Distinguished Research Fellow Prof Michael Bunce of Curtin University, in Perth, Australia, in the study.

His work - "Subsistence practices, past biodiversity, and anthropogenic impacts revealed by New Zealand-wide ancient DNA survey'' - was due to be published this week in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Dr Rawlence excavated a midden site in 2017 to collect a "frag bag'' for the study.

In the past, using the traditional morphological methods, researchers could identify only large bones that remained intact. The new technique involved a random selection of 200 bone fragments, which were pulverised into powder.

The calcium was then stripped and, from the calcified bone, scientists could take a DNA extract then "photocopy up this genetic barcode ... and we then sequence that''.

"You were [previously] looking at a puzzle where a whole lot of the pieces are missing,'' he said. Now, they had created "a lot more nuanced picture''.

By comparing bones excavated from caves that predated human arrival with bones from middens, the researchers were able to see the biodiversity New Zealand had lost.

Curtin University PhD candidate Frederik Seersholm said 14 of the species identified were extinct today; Prof Bunce said of the 10 kakapo types identified in the study "only one is still around today''.

Dr Rawlence said due to the new technique, researchers were now beginning to find kakapo and kea as well as eels and "lots'' of whales and dolphins in middens, which provided evidence to confirm what had previously been believed:

"Cuvier's beaked whale, dolphins, killer whales, fin whales, southern right whales - in middens - they were being eaten.

"We knew fur seals were vitally important to the diet and we assumed more important than sea lions, and elephant seals - but when you bring in this bone grab stuff, we now see that fur seal, sea lion and elephant seal were all equally important.''

The Australian researchers planned to expand the study to other parts of the world.