Instead of a road between Haast and Paringa there was a cattle track.

The wire formed a makeshift telephone line on the Haast-Paringa track and for Dunedin man Dick Williman, cycling with his Christchurch Boys’ High School classmates Jon Francis and John Tovey at the end of their sixth form school year, the wire would help them navigate the 1875 track.The track was originally built through thick West Coast native bush, to herd cattle from the Haast, Landsborough and Cascade River valleys to market north of Paringa.

Like all tales of adventure, that is just part of the story and Mr Williman starts at the beginning.As he tells it, inspiration for the trip came from a conversation with a man in a communal kitchen at the camping ground in Hanmer Springs who had just made the same journey.

"I had organised a small group from our church choir to cycle to the springs, and while cooking tea I chatted to this chap."From there the three teens formulated a plan.

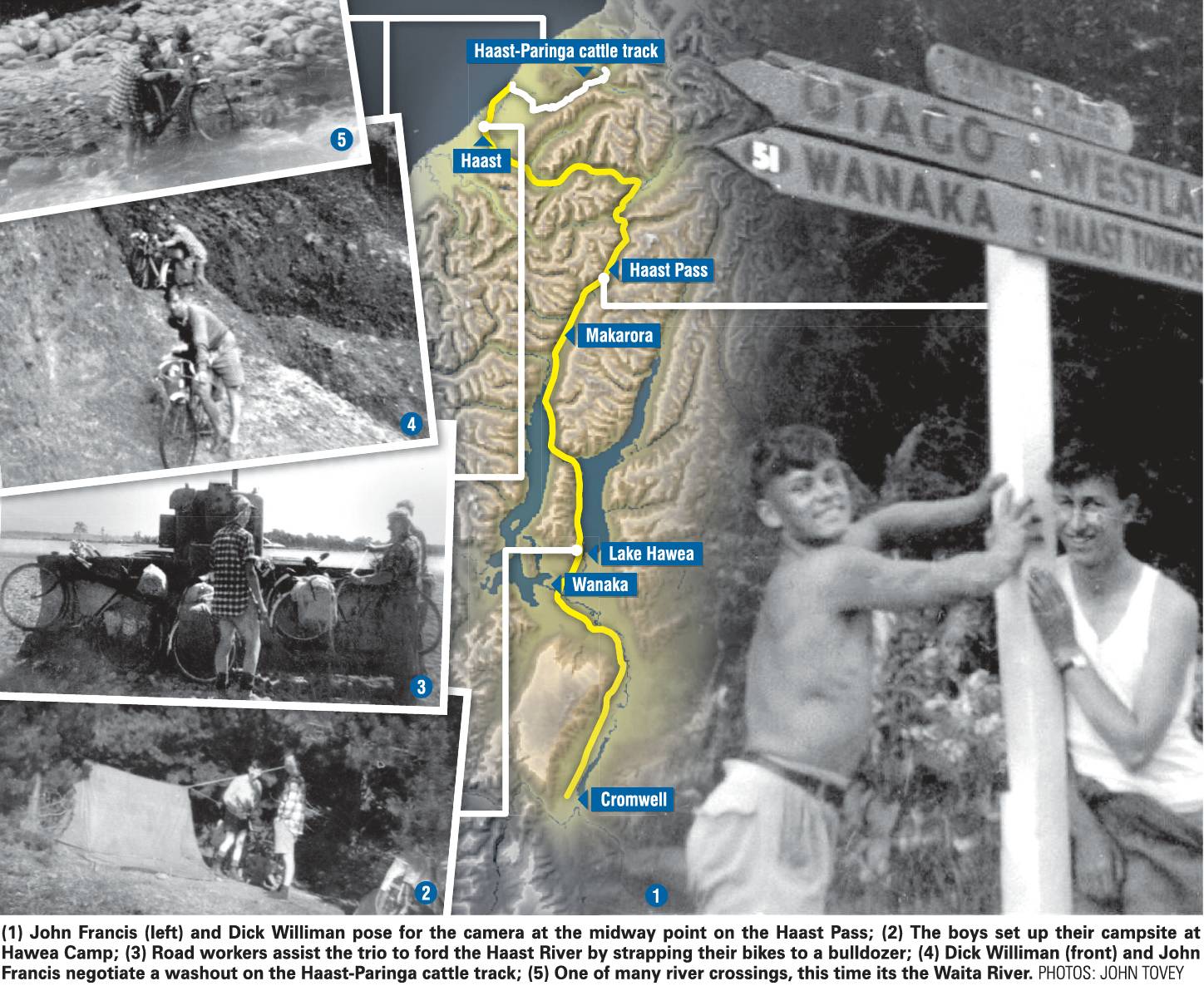

Take the train from Christchurch to Cromwell, cycle over the Haast Pass and up the Haast-Paringa cattle track, then on to Hokitika to get the train back to Christchurch.

It was a different era, Mr Williman says."In those times, rail was still the main form of land transport, government subsidised, and where they didn’t have rail, they developed a bus service.

"The whole transport system was controlled and monopolised by the government. Those were the days of NZ Railways Road Services buses."It was also an era of indirect routes, and with their bikes and gear the trio caught the steam train from Christchurch to Dunedin.

"We got into a very busy station with boarding school pupils returning home, either further south on the train we had come on, or going into Central Otago on the railcar that we were about to catch."The journey was slow — the railcar stopped at every station on the way, dropping off school pupils and supplies to the remote farming communities.

The teens took the railcar to Alexandra, then caught a NZ Railways bus to Cromwell. Their bikes were to follow them from Dunedin on the freight train to Cromwell the following day.They had arranged to stay the night with the family of another classmate (who Mr Williman remembers only as Simpson). His father was a teacher at Cromwell District High School and to keep them entertained Simpson’s father took them rabbit shooting.

The following morning their adventure began — cycling to Hawea.As to their wheels, mountain bikes they were not.

"Our bikes were pretty ordinary — standard 26-inch wheels with three-speed Sturmey-Archer gears and ordinary road tyres."The trio reached the Wanaka-Hawea turnoff, noted it was 3 miles (4.8km) to Wanaka and decided to skip it.

That is something Mr Williman regrets, as Wanaka was in its infancy and he would not see the town until sometime later when he lived there as a teacher at Mount Aspiring College.Instead, they headed on to Hawea and a camping spot for the night.

Hawea also marked the end of the sealed road. From there it was shingle through to Makarora and over the Haast Pass.Mr Williman describes an easy gradient to the top of the pass and then steep incline down the other side to where they set up camp near the Roaring Billy Falls.

Into the wildernessHere is where the tale becomes wild, he says.

The last section of the road into Haast was still being formed."It was particularly rough with big stones — not good on the tyres and led to one of our early punctures.

"John Tovey had packed a spare tube, fortunately."It was not just the road that was being formed. Piles were still being driven for the Haast River bridge — making for a memorable river crossing.

"Whether the workers admired our pluck or simply took pity on us, I don’t know, but they kindly took us across the river on the bulldozer with the bikes tied on the front."The section north of the river was close to the beach and a sandy track led through the scrub.

As well as sandflies, who seemed to whisper "should we eat them here or take them away?", there were rabbits, he says."Jon Francis had brought his .22 rifle with him. He stopped us so as to have a shot at a rabbit 50 yards ahead — immediately, hundreds of rabbits ran everywhere."

That evening they reached the Waita River, where the track turned inland."We started heading up the track with some more interesting river crossings. Eventually, we lost all sign of the track."

The braided stream had obliterated it — they were lost and a map was of no use."We set up camp for the night and discussed what to do next. Our AA roadmap of the South Island was not proving very helpful."

At this point the trio decided to abort the mission.Cue help — and some No 8 wire.

"We had not gone far when we met a horseman. ‘Where does the track go?’ I asked."He told the horseman there was no way they could traverse the rugged terrain with their heavily loaded bikes, but the man, Joe Riskow, a Ministry of Works roadman charged with maintaining the south end of the track, said "just follow me. Don’t worry, the wife is walking along behind".

The couple lived in a hut at Coppermine Creek and had been into Haast to get their weekly supplies. His wife had a sore back and had chosen not to ride."We followed them and had morning tea with them at the hut.

"My next question was, ‘which way do we go now?"’Mr Riskow’s answer was "just follow the phone line".

In the 1930s a phone line made of No 8 wire had been installed — but it only solved the navigation problem in part."By this stage large parts were missing but every now and then we would find a section of No 8 wire strung up between some trees."

They found some sections of the track to be in reasonable condition and could occasionally ride, but erosion had caused major problems in other places.The trio occasionally spotted deer on the track ahead, but Mr Francis’ attempts to shoot one failed.

The second night was spent camped on the track and the following day they met the roadman from the north end of the track, who perhaps had gone bush a little too long."He walked past us going the other way, didn’t speak, just kept his head down.

"He was based at Blue River Hut [also known as Blowfly Hut]."Out of the wilderness

It was a comparatively short distance from there to the road near Paringa. The Blue River crossing was a bridge built to get cattle across in those days.From Paringa it was a comparatively straightforward cycle to Hokitika, Mr Williman says.

"We even got back on to tarsealed roads after Franz Josef."The Mt Hercules section between Fox Glacier and Franz Josef was to prove challenging, especially for Mr Francis.

"He had managed to break the gear-chain mechanism on this bike, so he was stuck in top gear all the way.They also had to negotiate a number of swing bridges, including the Waiho River Bridge near Franz Josef, a later version of which was destroyed by flooding in 2019 and replaced in 18 days.

Sixty years on, Mr Williman pauses to reflect on the adventure."I often wonder what my parents must have been thinking when I planned this trip.

"Clearly they had little idea of the challenge I was taking on and the possible risks of venturing into the wilds of South Westland."Upon their return and sharing tales of their adventures around the kitchen table, his father Alan became enthusiastic about repeating the feat.

The next year he, his father and uncle Brin drove down to Paringa with their tramping gear."We had my father’s Vauxhall car and my cousin Andrew Eastcott and his wife Jean drove his Fiat 600 to Haast.

"We walked through and met halfway and swapped car keys. Fitting Dad, Brin and I with our packs into the Fiat was a bit of a challenge."They then drove back to Christchurch and swapped cars back.

On this trip the landscape had already changed. The Haast Bridge had been completed to the stage where the approach at the Haast end was finished, but not the approach at the north end."Andy drove the Fiat across the bridge and then backed back, claiming to be the first car across the bridge.

"It was officially opening some weeks later."Does he have any regrets?

None, he says."Bicycles gave us the freedom to explore. It’s not like we had cars in those days — we were just schoolboys."

- This account is based on Dick Williman’s own recollections which he compiled at home during the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown.