In late-June, 1970, as Joyce Kempton stood in the fading light at the Balclutha bus stop waiting for her fiance, Sid Beck, to pick her up in his Mark II Zephyr, she was acutely aware of the air of concern pervading her hometown, Kaitangata.

Joyce had much to be optimistic about. She was in her first year out of teachers' college. She was enjoying having her own class at Gore Main Primary School. When the school year ended, she and Sid, a fine, young "Kai'' man and a capable builder, would be married. The thought of them getting their own place and starting a family made the future Mrs Beck smile.

And to cap it all off, this weekend she was celebrating her 21st birthday; a small, dinner party with half a dozen childhood friends at her parents' home in Salcombe St, overlooking the snug South Otago coastal township.

The Government had announced it planned to concentrate coal mining in Southland, Westland and at Huntly, in the Waikato.

For almost a year, although there had been no formal notice about when Kaitangata's remaining large underground mine, Lockington, would close, rumour and consternation had been rife.

Every weekend, when she returned home, Joyce could feel the "doom and gloom'' in the township.

"I remember living in a household of `What on Earth are we going to do?','' she recalls of that time.

"There were all these discussions around the table about `Where is your Dad going to go?' and `What are you going to do?'.''

Then, in February, it had been announced the mine would shut in September. Standing in the twilight that June evening, Joyce felt foreboding but could not foresee the many changes the next few months would bring.

Half a century later, Kaitangata's experience is now a global one. The age of automation is about, or may have already begun, to alter everything. We do not yet know exactly what that disruption will look like. But the air is full of anxious conjecture about the future of work.

There is plenty of speculation. Most of it quite chilling.

Some have estimated almost a third of the global workforce will be automated within a dozen years.

International change consultancy McKinsey & Company is telling its clients that robots and Artificial Intelligence (AI) could fully replace 5% of all jobs and could do a third of the activities in 60% of all occupations.

"This means that most workers - from welders to mortgage brokers to CEOs - will work alongside rapidly evolving machines,'' McKinsey says in a 2018 report, AI, automation, and the future of work.

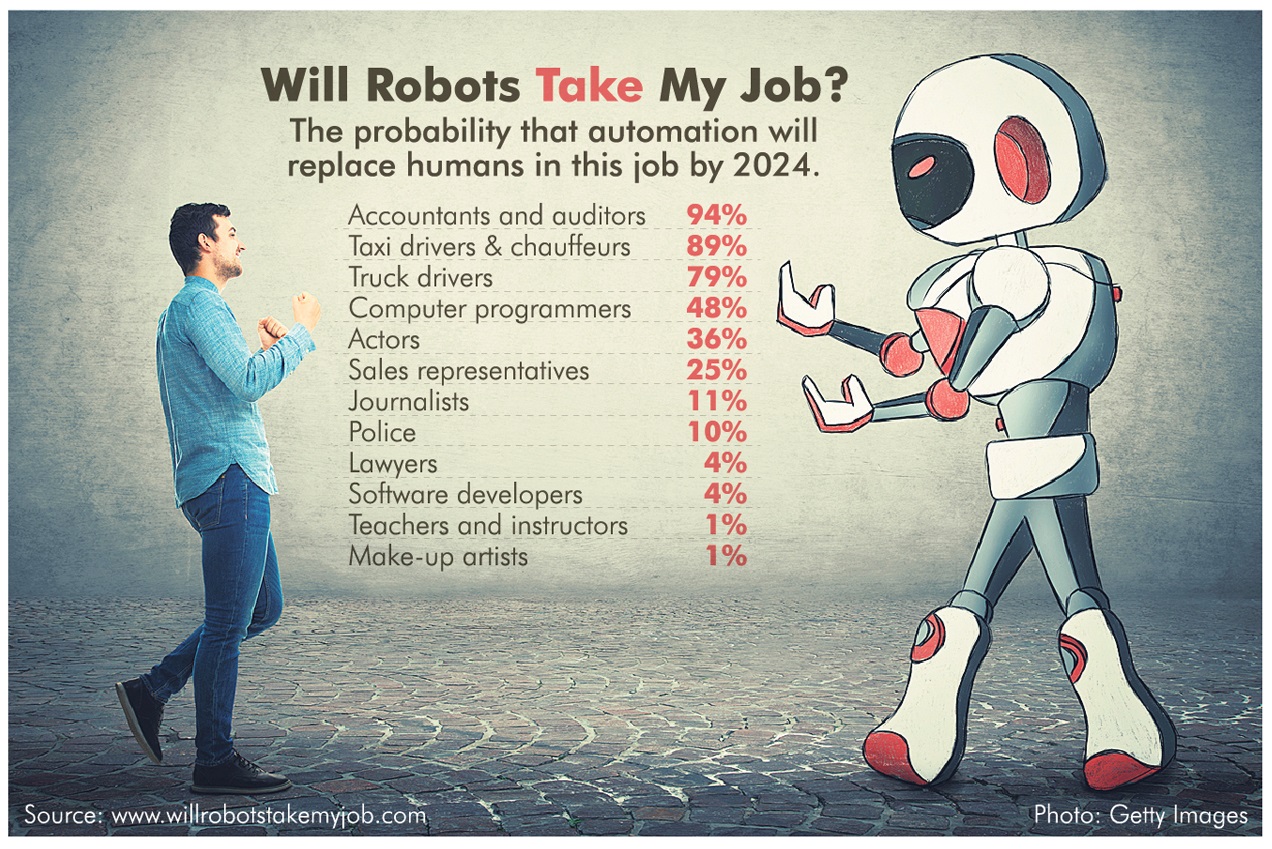

Sharpening that up, a website using research by Oxford academics Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne estimates the likelihood, across 702 job types, of robots replacing workers by 2024. Teachers are in the clear - they are on 1%. Journalists are on 11% and actors are on 37%. Accountants and auditors face extinction - they are on 94%.

Associate Professor Robert Pinter, who gets lots of invitations in Europe to deliver his talk Will Robots Take Our Jobs?, thinks most people are too worried about the immediate future but do not grasp how significant the changes will be long-term.

Prof Pinter works in the department of information and communication, at Corvinus University, in Hungary, and is head of consumer research for eNET Ltd.

"I think people expect much faster and less profound changes than we will finally face in the next decades,'' he says.

It has been suggested that change in the workplace is already 10 times the scale and 100 times the pace of the Industrial Revolution.

In this country, the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research has estimated 46% of jobs could be taken over by machines by 2035.

The Government is listening, with understandable concern.

It has charged the Productivity Commission with examining the future of work and reporting back on how best New Zealand can "maximise the opportunities and manage the risks of disruptive technological change and its impact on the future of work and the workforce''.

BUT not everybody is so glum.

Kinley Salmon says the estimates, while scary, are misleading.

"Change is coming, as it always does, but not like that,'' Salmon says.

"Moreover, we are not powerless to shape the future.''

Salmon has flown high in 31 years. Born in Nelson, New Zealand, educated at Harvard, he has worked for McKinsey & Company, written for The Economist and now works in Washington, DC, as an economist at the World Bank.

The world is his to shuck. Tonight, he is speaking by phone from Jordan, in the Middle East. He is talking about his personal research on what the future of work might look like in Aotearoa, which he has boiled down to a 300-page book with 40 pages of endnotes - Jobs, Robots & Us: Why the future of work in New Zealand is in our hands.

"The evidence suggests the robots are not that close to the gate,'' Salmon says.

"But I'm not claiming no changes are coming. We are likely to see changes over time, especially to the way we work.''

He says historically low unemployment, slow productivity growth and little sign of rapid job turnover all belie the assertion that automation and AI are in the process of making us all redundant.

In fact, compared with the rest of the developed world, it is likely that fewer New Zealand jobs will be stolen by robots, he says.

"This is in part because a lot of Kiwis work in areas like professional services that are difficult to automate, while fewer work in manufacturing, which is easier to automate.

"We spend more time in fields, less time in factories, and a lot more time showing other people our glaciers, boiling mud and beaches.''

Of course, there is a lot of uncertainty around all of this, he admits. But even if many jobs are at least partially automated, new jobs we have not yet even thought of will be created. And with machines doing more, ours could be a future of much less work and plenty of time for people and play.

Salmon agrees, however, that there are some significant challenges ahead.

Two of the key challenges are related: ensuring swathes of the population do not fall into poverty during this transition and making sure there is enough demand (for demand read, income) for the greater quantity of "stuff'' that will be produced by more productive, automated, industries.

"There's a bit of a risk if we are in a very unequal society that people won't be able to participate in that way and it could cause trouble for the whole equilibrium,'' he says.

Prof Pinter agrees.

"The main challenge will be economic: how will people earn enough money to keep their ordinary standard of living?,'' he says.

"This is not something in the distant future.''

It is a worrisome development that already looks to be under way. The hollowing out of the middle class, pushing people towards poverty or wealth, leaving a gaping hole in the middle, has been regularly signposted in recent years.

Last month, the OECD warned middle-class households were struggling with stagnating incomes that failed to keep up with the rising costs of housing and education.

The OECD report said traditional middle-class jobs were increasingly being replaced by temporary or unstable jobs, often offering lower wages and job security.

"Today the middle class looks increasingly like a boat in rocky waters,'' OECD secretary-general Angel Gurria said at the report launch.

"Governments must listen to people's concerns ... This will help drive inclusive and sustainable growth and create a more cohesive and stable social fabric.''

During the past five years, depending on which sector you work in, your real income (taking the rising cost of living into account) has either increased 12% (in the transport equipment, machinery and equipment manufacturing sector), been stagnant (information media and telecommunications; central government administration, defence and public safety; and, public administration and safety) or gone backwards (meat processing).

During the past decade, the number of Kiwis unemployed has increased 49%, those underemployed (working but not able to get enough work) has increased 61% and the number

underutilised - that is unemployed, underemployed or given up looking for work - has grown by 38%. Oxfam's latest annual Inequality Report reveals the two richest people in New Zealand added $1.1billion to their fortunes, while the wealth of the poorest half of the country decreased overall.

The richest 5% of the population now collectively owns more wealth than the bottom 90%.

Automation, if we are not careful, could exacerbate that trend.

KAITANGATA was a compact but bustling town. Until September 30, 1970.

Nestled in sheltered, flat land close to the mouth of the Clutha River, the township did very nicely on the back of coal for more than a century. It was the second town in New Zealand to get electricity. Work was plentiful, pay was handsome. Everything you needed could be found without leaving town.

Fred Uren, now 82, was born here. Like his father, he was a coal miner. When the Lockington mine shut and the jobs disappeared it was a big shock to the town.

Fred got work at the local hotel and then at ''the freezer'' in Balclutha.

''We were very, very lucky there were a lot of other industries in the region at the time,'' Joyce says.

Kaitangata was reduced to a dormitory town for people working elsewhere.

Once, the town had boasted 1500 residents. Today, it is half that. In 1970, it still had a Four Square store, a Post Office and bank, a pub, a movie theatre, a butcher, a lingerie factory, a cheese factory, a takeaways and a dairy. Today, it has a dairy.

If Salmon knew the history of Kaitangata, he would likely point to the resourcefulness of the mine workers in securing other employment. It is, perhaps, a good illustration of his main thesis - the future does not just happen to us, it is a result of choices; so, we do not need to fear automation and AI; instead, we need to make choices to fashion the future we want.''Above all,'' Salmon says, we need to ''reclaim our sense of agency to shape the future''.

He sees two, distinct, possible futures for New Zealand, three decades hence.

In one scenario, there has been significant technological progress. Society and the economy are still structured around work, high employment and inclusive growth. Jobs for humans, in this future, come from the creative and innovative sectors, high-productivity growth industries, newly created high-tech tasks and personalised services.

In the alternate future, significant automation has also occurred but paid work is an exception rather than the norm. Most people live off a basic universal income and the dividends of state-provided shares in technology companies. Education is about self-creation not employment. Economic growth is no longer an imperative. There will be lots of time for people and play. Finding meaning and happiness outside of work will be a significant challenge.

Both futures, Salmon says, will require us to choose that path and actively work towards it.''Recognising how much we can shape the future of work is the first step to engaging in the political and public debate to do so.''That may help bring things that currently seem politically unattainable into the realm of the possible.''

Salmon is supported in that view by, among others, Prof Pinter.''We may form it and make it together a better place,'' Prof Pinter says.''However, there is also a scenario that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer if we misuse this new technology.''

That future is up to us.

''It begs a crucial question. Do we, in 2019, have that sense of agency? Do we still believe we can change things through the traditional, democratic, political process?It appears that, for increasing chunks of the global populace, the answer is ''Not so much''.

Ethnopopulism is the smoking gun; the signal that increasing numbers of people no longer trust the system.

Ethnopopulism is a blend of populism and nationalism. Populism pits people against wealthy and powerful elites. It is fed by growing inequality, loss of confidence in government institutions and market-focused neo-liberalism, and the rise of social media-enabled conspiracy theories.

Nationalism pits the nation against the outsider. It values members of a nation state or ethnic group over other groups.

Put them together and the perceived enemy is outsiders (migrants, ethnic minorities, foreigners) and those in power, who together conspire to undermine ''us''. The belief is that the system is broken, the odds are against us and a strongman is needed to defend us.And that sort of thinking is on the rise, Prof Erin Jenne says.

''These sentiments are not held across all segments of society, but are concentrated among individuals who feel alienated or disenfranchised by the system overall.''

The weight of the evidence suggests that growing support for populist parties and political figures in liberal democracies is best explained by declining levels of trust in mainstream political institutions.''

Prof Jenne points to the rise of right-wing populist governments in Austria, India, Russia, Turkey, the Philippines, Poland and Macedonia. And to the rise of left-wing populist governments in Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador and Argentina.

She points to the election-winning, anti-migrant and anti-establishment rhetoric of US President Donald Trump. And she highlights how unsubstantiated conspiracy theories are entering mainstream politics.

In March 2018, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, of Hungary, declared that his country was being ''invaded'' by ''foreigners from other continents who don't speak our language, respect our culture, our laws or our way of life''. Orbán repeated the baseless theory that billionaire philanthropist George Soros ran a global network that wanted to ''replace'' native Hungarians with migrants from the Middle East and North Africa.

AUTOMATION seems to be making it worse.

''The core driver behind support for right-wing populist parties seems to be rooted in bleak prospects and the realisation that one does not belong to the winners of economic modernisation,'' he says.

Prof Pinter predicts that if we don't get the transition to automation right we won't need to worry about an apocalyptic ''rise of the machines'', because people will revolt first.''Men will rise earlier than machines in a world where the workforce is only [seen as] a cost that should be minimised,'' Prof Pinter predicts.

Salmon agrees it is easy in today's world to feel disempowered. However, ever the optimist, he believes New Zealanders still hold faith with the system.

''I think New Zealand's politics has been, in some ways, less impacted by some of what we've seen overseas.'

'He points to the sorts of choices for progressive political and social change New Zealanders have made in the past and believes we can continue to do that.

The lesson of the Great Depression, in Germany, the Global Financial Crunch, in the United States and the United Kingdom, and the 2015 Refugee Crisis, in Europe, is that a moment of significant crisis can be all that is needed to make those seeds sprout and bloom.

To prevent that, Prof Jenne says ''we ought to work to identify and marginalise far-right leaders and activists, while extending a helping hand to those who are susceptible to far-right messages due to their economic or social marginalisation''.

Dr Kurer believes ''simple expansion of traditional redistributive welfare state spending'' won't be enough.

Workers do not primarily want money thrown at them. ''Appreciating and re-valuing the role of `ordinary work' and strengthening labour as opposed to capital'' will be key, he says.

But it is important we do not leave it to the politicians to determine what that future should look like, Salmon says.

A society-wide discussion is needed, he believes.''I'm still relatively optimistic, certainly in New Zealand, about the ability of our political system ... [and] the democratic process to tackle some of these big questions.

''I think it is good to encourage debate. I would love to see a focus on the longer term ... a debate grounded in the evidence ... [and] a debate that recognises and embraces the extent to which we have an influence over what happens in the future.''

All this takes time. So the time to start is now. Because, getting to a better future can take decades. As Joyce and Fred well know.They both stayed in Kaitangata. Because, despite the mine closure, the loss of jobs and services, it was home.

They talk proudly about the new lease of life Kai is now experiencing - the newcomers buying land, building houses and opening businesses; the new BMX track, skatepark and community centre; the growing school roll - 50 years on.

Comments

Class is culture, tradition and upbringing, not contingent upon income or lack of it. 'Shabby genteel' is middle class. Loud, shouty individual self interest is indeterminate, not class as we know it.

Machines are programmed by people. If accountancy goes AI, will IRD be far behind? Who argues the toss in tax evasion cases?