The Ministry of Health is aware of the risk, and has moved to meet it by putting in place a four-stage alert system, and expanding the country's ICU capacity.

Researchers at Te Pūnaha Matatini, New Zealand's Centre of Research Excellence in Complex Systems and Data Analytics, have been developing models that show what hit the health system could be in for.

The centre's director, Professor Shaun Hendy, said based on overseas data, around 10 per cent of people who catch Covid-19 would need to be hospitalised, and around one quarter of those cases would need intensive care to survive.

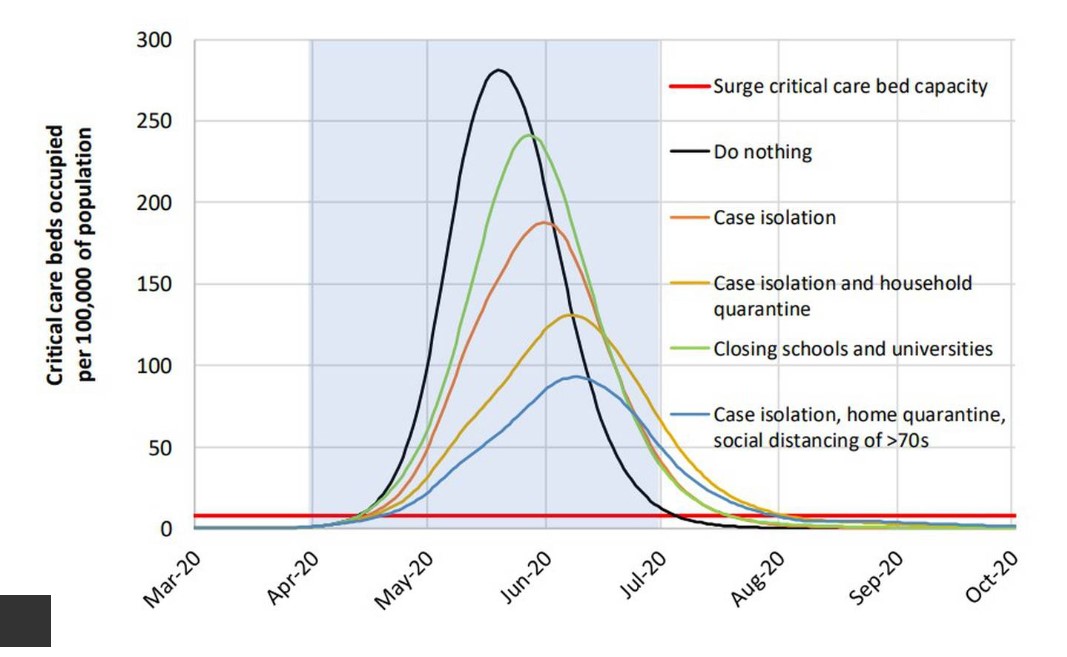

"If we don't take measures to control Covid-19 then our model suggests that the number of people needing intensive care will be about 10 times the capacity of our hospitals, which will mean many tens of thousands of fatalities," Hendy said.

"It is crucial to ensure we have enough intensive-care beds, as well as the healthcare workers to manage them, so that people receive the care they need to keep them alive."

Some early, but simple, models threw up the potential for 100,000 hospitalisations and 25,000 deaths.

Another initial model his colleagues built – assuming there was 300 ICU beds, which was a third more than current numbers – showed an overload of ICU beds would mean the difference between death rates of one and two per cent of all cases.

Hendy said the difference between taking strong measures could see 10,000 deaths, versus 60,000 deaths and a 80 to 90 per cent infection rate if nothing was done.

Today, Ministry of Health director-general of health Dr Ashley Bloomfield said such modelling was "very helpful", in that it showed what would happen if New Zealand didn't act quickly and with certainty.

New Zealand was at level two of its four-stage alert system to manage the pandemic.

"The reason that [levels] three and four are there is because we are signalling that we may well need to move to those - and the reason we would move to those is to avoid a situation where we overloaded our healthcare system, including ICU capacity."

Hendy said that had scenario had already played out in Italy, forcing doctors to choose who received intensive care - or effectively, who survived.

"That is a horrible position to be in, and it means the fatality rate will be higher than it would be if they had more ICU capacity or had adopted an aggressive suppression strategy earlier on," he said.

The "suppression" strategy was one of two approaches outlined in a new report, by Imperial College London (ICL) researchers, which has prompted many governments – including New Zealand – to rethink their approach.

That aimed to stamp out the spread as much as possible until a vaccine arrived, through tough control measures like isolation, quarantine, social distancing and school closures early, before an outbreak could take off.

The other approach – mitigation – allowed the disease to spread, but with measures to isolate suspected cases and those at risk like elderly, so the rate would be slowed enough for hospitals to cope.

The ICL analysis found suppression would have a better chance of sparing the health system from overloads – and New Zealand officials were now looking to manage any outbreak through a series of smaller, controlled surges rather than one "flattened" peak.

"The best approach, we think, is to adopt aggressive suppression measures as soon as practicable."

Hendy added there was still much to be learnt about the virus, and some of the data that was coming in from other countries might not be as applicable to New Zealand as time went on.

"Also, we have used a relatively simple model, which effectively treats New Zealand as one big city where anyone has the chance of infecting anyone else in the country," he said.

"What we want to do next is to build a regional model so we could see what the effect of quarantining or restricting movement in different parts of the country might be. This might allow us to use a containment strategy similar to those being used in South Korea."

Last week, Bloomfield said the country's approach had pivoted from trying to flatten one large peak of cases, to using controls to manage a series of peaks to assist the healthcare system.

All models had shown that one single wave of transmission - or peak - would cause cases to take off.

The ICL report had been "very crucial" in changing tack to prevent that happening.

"Our approach is – and this is what successful countries have done – is you want to have a series of small peaks over a long period of time."

Hendy pointed out that mitigation strategies relied only on getting R0 – or the average number of people who catch the disease from each infected person - below one.

"Only China and South Korea have managed to do that, so it would be risky to rely on a mitigation strategy alone."

The number of ICU beds per population in New Zealand has fallen steadily over the last 20 years, with the country now well behind comparable countries, including Australia.

Comments

Weigh up the costs of widespread testing compared to over-run hospitals. The health line isn't coping, how are our hospitals going to cope if this gets out of control.

Sorry, but what other option is there than to implement some form of widespread testing as soon as pratically possible. This should be our number one focus. There is just too much at stake. The longer we wait, the greater the impact. We are a very small isolated country that is currently in lockdown. If ever there was a time to ramp up testing, it's right NOW. We are told by AUT there is enough reagent. (on their website). And no doubt the suppliers overseas are working flat out to make more. We could very easily train thousands of people to administer testing, right now, people will be looking for jobs, and many just want to help. We have an industrial base that could manufacture testing kits. We have labs that could be redeployed for Covid 19 testing. A foot forward approach could save thousands of lives and get our domestic economy back on it's feet. Overhelmed hospitals we do NOT need. The balance of probability is tipping, how long before we start testing? Every effort should be made to make kits and TEST.