(Brett McDowell Gallery)

Maps are fascinating. Functional yet aesthetic, representational yet coded, they describe our world and hint at its mysteries. It is no wonder that so many artists are inspired by them.

Maps have been a leaping-off point for three current local exhibitions.

At Brett McDowell Gallery, Craig McIntosh uses imaginary landscapes to create "manufactured topographies" — three-dimensional landforms of sculpted argillite and basalt. The rocks, harvested from the land, themselves become landforms, strands of red carbon fibre acting as grid references for some never-drawn map.

Alongside these works sits another series: silver-black crockery hand-shaped from slate, the surfaces heavily worked with graphite. The pieces are an elegy to the artist’s father and to the effects of dementia, the sculptures being shadows of everyday items, the graphite gradually leaving the surfaces like so many forgotten memories.

The artist does not completely abandon his jewellery roots, with two large pendant pieces designed as wall art. In one, a double-sided piece shows the lustre of mother-of-pearl on one side, and a similar lustre of carbon fibre on the other. The other piece is an impressive sculpture of a crushed can, remarkably carved from a large piece of Japanese boxwood.

Both pieces are deliberate poignant blends of the natural and the artificial.

(Milford Galleries Dunedin)

Where topographic maps form a basis for McIntosh, Roger Mortimer is inspired by medieval cartography and art.

Mortimer’s works, both in watercolour and in tapestry, take the iconography of early religious art, especially depictions of hell and damnation, and juxtapose it with the coastlines and Māori place names of New Zealand.

The result is as dramatic as it is fascinating. Figures that have stepped from Bosch’s paintings of hell or Botticelli’s illustrations of the works of Dante are adrift in Foveaux Strait, Crusader castles and ascetics are placed in the Marlborough Sounds. A cognitive dissonance results, as we see these lands charted as they may have been charted if Europeans had arrived centuries earlier. There are more modern nuances in the works, however, especially in relation to colonialism. People sit among the nikau palms petting the introduced rabbit and hedgehog, and others are segregated with No 8 wire fences.

The works are beautifully created, and some indication of the artist’s processes can be gained by those cases (such as Genuine Prosperity and Whatipu II) where the same scene is depicted in both watercolour and in tapestry — tapestry which even goes so far as to copy the runnels of dripping paint. The similarities and differences are an intriguing insight into the working and working out of the art.

(Bellamys Gallery)

Maps are also an inspiration for half of a joint exhibition by Pauline Bellamy and Manu Berry.

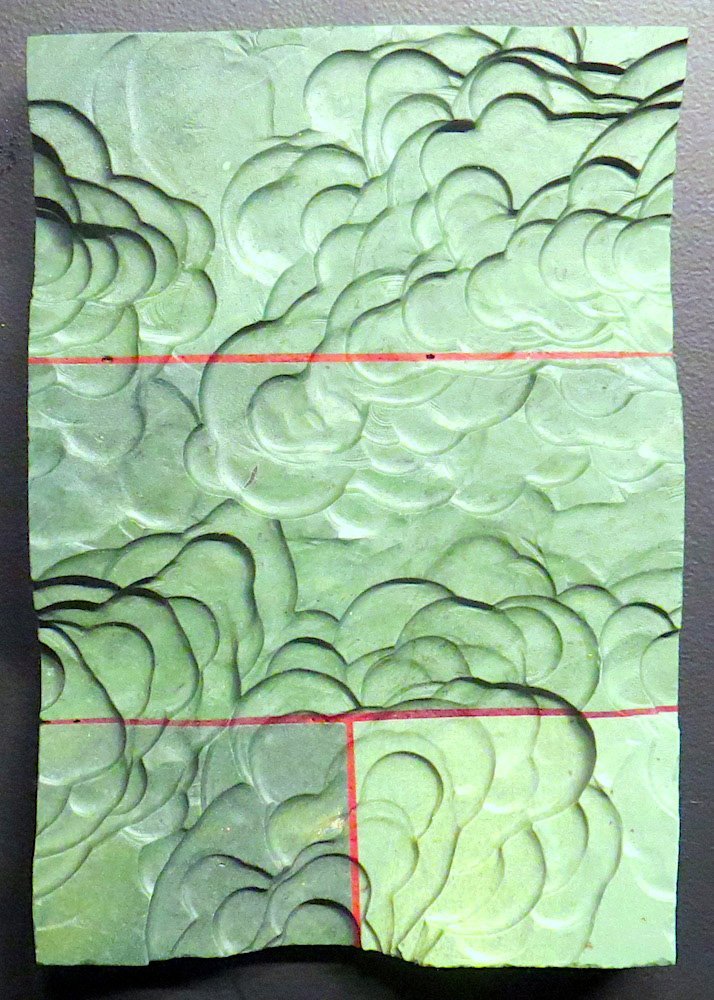

Berry’s massive woodcut prints display stylised isobars, swirling across unseen oceans and landmasses. In a trilogy of works, the landmass is New Zealand, the sharp bends and folds of the lines suggesting the location of mountain ranges. Other works depict the air masses of the globe’s overall weather, and also of the two polar regions.

The images are companion pieces to poet Richard Reeve’s book About Now, and its verbal depictions of the land and weather of the country.

Stark in their simplicity, Berry’s images work as both forms and metaphors on many levels. We see tree-rings of weather, measuring out the changes in the climate. We are hypnotised by the swirls as we are by Bridget Riley op-art. And again, we see histories and topographies.

The tree-ring similarity is an important link to Pauline Bellamy’s acrylic paintings, deeply impastoed images of the trees and the land, many of them inspired by a visit to Canada. In images like Pathway and the painting Aspen II, the land becomes a series of bright impressionist forms, the trees standing as searing, shining sentinels in the vast emptiness of the country.

By James Dignan