As an 8-year-old, Vincent Ward began to draw his father’s hands.

A World War 2 veteran, Ward senior had three-quarters of his body burnt during his service including his hands, which were badly puckered. He was continually receiving skin grafts as Ward grew up.

Living on an inhospitable hill country farm in the Wairarapa that used to be a World War 1 artillery range, the Ward family persevered.

"He was trying to restore the land at the same time he was trying to restore himself," Ward said.

To make ends meet, Ward senior was a fencing contractor, completing more than 32km of fencing.

"The fences were so straight and when you see them on the air, they’re just like straight lines that go over the cliff. I mean, just unbelievable."

This was the starting point for Ward’s work "Palimpsest/Landscapes".

"In my mind, the terrain became these mapping-like forms of his attempts to keep out entropy and to restore himself. That is how I came to it."

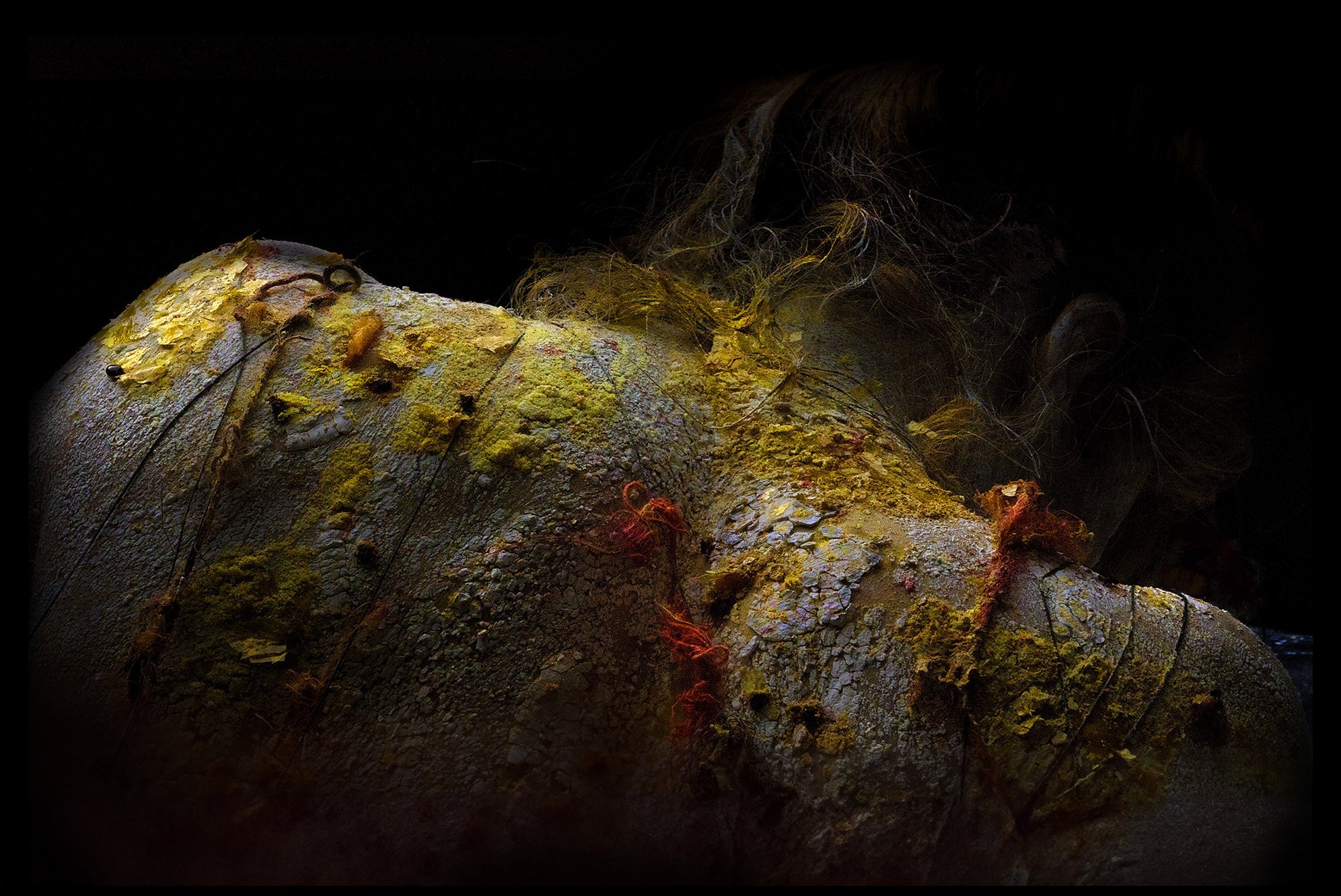

He brought together a group of dancers he had worked with before and used their skin as canvases. Using skin-friendly inks, dyes, chalks and powders, he created his visions with the assistance of the dancers and a team of helpers.

"I’ve created a pallet of materials that I could work with safely to create that atmosphere, because each of the works is sort of like a different sort of form, it’s like a reef or it’s a planet or it’s a, you know, a desert or a forest floor ... and so I gradually evolved a painting technique which has been photographed to evoke those femoral landscapes."

Each shot required two weeks to prepare the materials. On shoot day, he would have 1.5hours when the natural light was right in his warehouse studio to do the photography. It then took about a week to clean up afterwards.

"I don’t see myself as a photographer. It’s what’s in front of it that I try and create."

Ward’s studio is a bunch of small workshops where he can make lots of different things depending on his latest project.

"I try to create a space that’s agile, that can pivot so I can move from one medium, whether it’s welding steel rods or, you know, doing photo shoots or doing paintings."

Often living there during these periods of work, Ward revels in having all of his gear in close proximity, allowing him to rig up whatever he needs.

He also works with the dancers, taking on board their suggestions and their body types.

Ward then spends up to a year working on the images to find the right one and then print it to his specifications.

"Those images started in I think 2016 and then they’re still being finished now. They sort of become obsessive and drive my printers crazy because I keep coming back and then I keep tearing up prints and doing all that sort of bad artist c... — I’m running it and I’m responsible for it financially so, you know, I just keep going until I get what I want, basically."

A special aspect to the work is calligraphy partly done by Wang Dongling, one of China’s greatest living calligraphers, known for large scale abstract works he calls calligraphic paintings.

Ward (69), who lives in Auckland, was working in China at the China Academy of Art, where he met Wang who was keen to collaborate. When Wang came to New Zealand, he worked with Ward and a team of Chinese calligraphers to help bring the idea to life.

"He’s such a gentle wise man with a passion for his work. That idea of words and stories that have fragmented and disappeared and reshaped and reformed into new narratives about that same place where the land itself is reformed."

Ward’s work in film-making transfers through to his art.

"I do try to create stillness within movement and movement within stillness, and that has very much to do with coming out of a cinematic concern for such a long time and I don’t see others doing it because they don’t come from that, they haven’t gone through an art school and then become a film-maker and then become an artist again."

He believes the work he has done in special effects in films with specialists in the field means he sees opportunities where others might not.

The "visual ambiguities" in this exhibition mean that it takes a while for people to realise the images are of human bodies.

"That it’s actually an image taken from the lower rib cage and looking down towards the hip, and that the body is actually completely transformed into a wreath through it’s materiality and you can’t see it unless you know to look for it."

From Ward’s childhood drawing his father’s hands, art continued to play a strong part in his school life. A series of head injuries boxing, wrestling and playing rugby put paid to any idea of a sporting career.

"I was banned from all that after my sixth head injury. And so I became a fine artist because of it. I went to the art room and would draw and paint."

Then in another twist of fate, at art school at Canterbury University he found he enjoyed animation and film work.

"The work I was doing was a bit more dramatic than what was currently the norm at the art school. And so I was doing drama as well and acting and so I ended up, you know, as an experiment doing film and then I just happened to do well at it."

His films Vigil (1984), The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey (1988) and Map of the Human Heart (1993) were the first films by a New Zealander to be officially selected for the Cannes Film Festival. Between them, they garnered close to 30 national and international awards.

What Dreams May Come (1998) won an Oscar and was nominated for two Academy Awards. Rain of the Children (2008) was picked by the audience to win the Grand Prix at Poland’s largest film festival. The film was also nominated for best director in New Zealand and Australia. The River Queen (2005) won the Golden Goblet in Shanghai.

Throughout this time, he never stopped drawing.

"I always saw myself as a painter, oddly enough, and so I never stopped doing drawings — conceptual drawings like for Aliens 3 or doing artwork for what films may come. That sort of goes through everything I’ve done, it’s part of the same practice, just different manifestations, a different way of presenting the images that are in my mind."

In 2008, he went back to being a fulltime artist, exhibiting his work in major exhibitions at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Gus Fisher Gallery and the Arts House Trust. In 2012, a high-quality large format art book titled Inhale/Exhale was published featuring images of Ward’s interdisciplinary artworks.

"I’m lucky to be able to do that and also to have a moderately successful career as a film-maker has allowed me to do some of that; you know, to go back to what I really am at heart and make those things."

Initially, he "robbed" his films of raw images, taking them back to what originally inspired him, finding the one frame out of millions and exploring that further for a body of work.

"Gradually, the work became more and more abstract. Always trying to find fresh ways to explore the human figure and to explore the consciousness, the transformational moment and the psyche."

Over the years, Ward, who was awarded an honorary doctorate in fine arts by the University of Canterbury in 2017, has also spent time in China. Ward was the first New Zealander to participate in the Shanghai Biennale (2012) and exhibited in the solo pavilion. He has also sat on the jury of the biennale, has done residencies at the Shanghai University School of Fine Arts and has been conferred a guest Professorship at the China Academy of Art, School of Fine Arts, in Hangzhou.

TO SEE:

Palimpsest/Landscapes: Milford Galleries Queenstown, until July 20.