Mila Makasini’s most ambitious design to date connects his architectural learning to his culture.

His concept for a cultural centre recently made the finals of the Best Design Awards, run by the Designers Institute of New Zealand. Earlier it won the inaugural student design award from the southern branch of the New Zealand Institute of Architects.

Auckland-born Makasini, who is of Tongan descent, said he was aiming not for a fale but a contemporary interpretation.

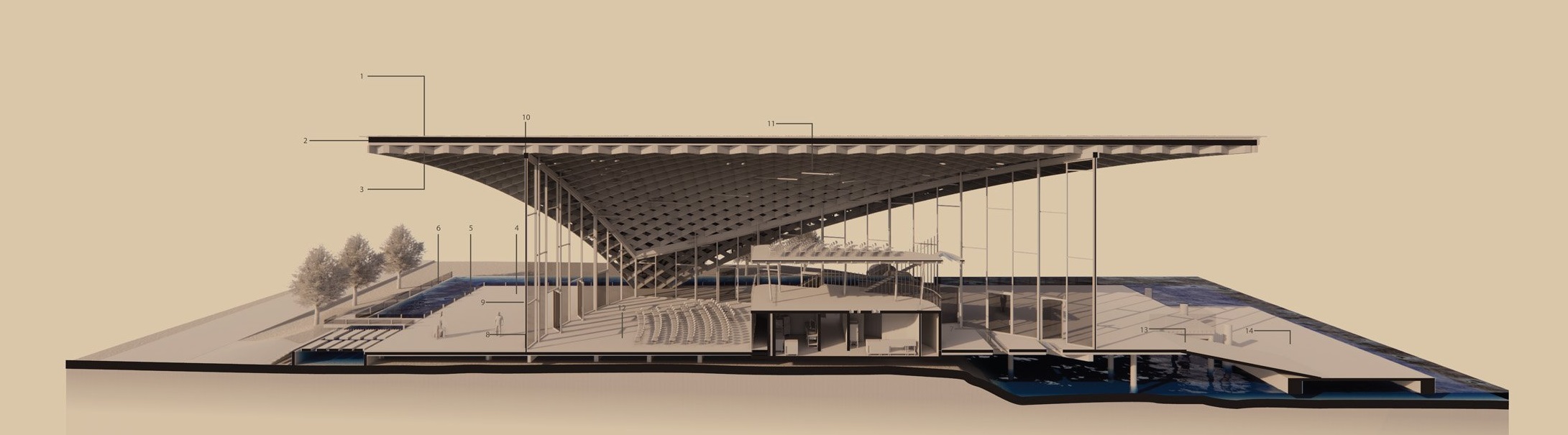

Inspired by Polynesian boat- and shelter-building technologies, the proposed centre was a lightweight timber structure which spanned a large area without the use of conventional structural elements.

Polynesian people saw the ocean as a space that connected rather than divided, he said. Voyagers looked to the constellations as they navigated the seas in lightweight vessels propelled by three-point, crab-claw sails. When they came across new islands, they upturned their canoes on their oars and paddles to form a shelter.

In Makasini’s concept design the superstructure of the cultural centre is a timber roof which in section is a pointed arch and in elevation is a sail. The cruciform plan is an interpretation of the Southern Cross constellation and the movement of stars is referenced in LED lighting in the ceiling.

A timber rain screen extends beyond the edge of the building envelope like a woven basket, while the glass frontage is open to the sea and sky.

With a lobby area, main hall and two upper decks, the centre could be used for meetings, dance performances, celebrations, crafts and exhibitions.

Given the importance of water and navigation to his ancestors, Makasini felt the centre should be close to Otago Harbour and eventually settled on a site in Magnet St.

Covid-19 has delayed the Best Design Awards until February, but being shortlisted in the student spatial category was recognition for an architecture school with "great" facilities and lecturers, he said.

The architectural studies course was demanding and life became even busier after the birth of daughter Aliana early in his second year. But he grew to like it "more and more" and by his third year was regularly spending 12 hours a day in the studio, staying alert with coffee and loud music and occasionally sleeping overnight on the floor.

He also made time to enter the 2020 Dunedin Heritage Awards, where his concept to develop a former Rattray St furniture factory into apartments was highly commended.

The 22-year-old, who appreciates Gothic revival architecture, said he planned to do his master’s, then work towards becoming a fully fledged architect, but had no desire to "go to Auckland and work on multimillion-dollar skyscrapers".

"The people of Dunedin and the buildings and spaces we have are amazing."

As for the cultural centre, it remains a concept but he would be happy if even a smaller version was built.

"I’d love to see it come to fruition one day, so I’ll definitely keep the plans in my back pocket," he said, laughing.