Hocken Collections is fortunate to hold Jones’ papers relating to his dedication to tattooing, which were thoughtfully donated by his daughter Ellen in 1987. The collection features multitudes of sketches and drawings of his tattoo designs, scrapbooks full of flash (pre-designed pieces) and diverse publications supplying his need for reference and inspiration, ranging from Disney cartoons to a book titled Japanese erotism.

Aotearoa New Zealand naturally features frequently in international literature about tattooing due to the Māori practice of tā moko. Less attention is allocated to commercial tattooing practices, which grew in prominence during the 20th century in the developed world, moving into the current century’s mainstream. This collection allows us to consider how commercial tattoo artists developed their craft.

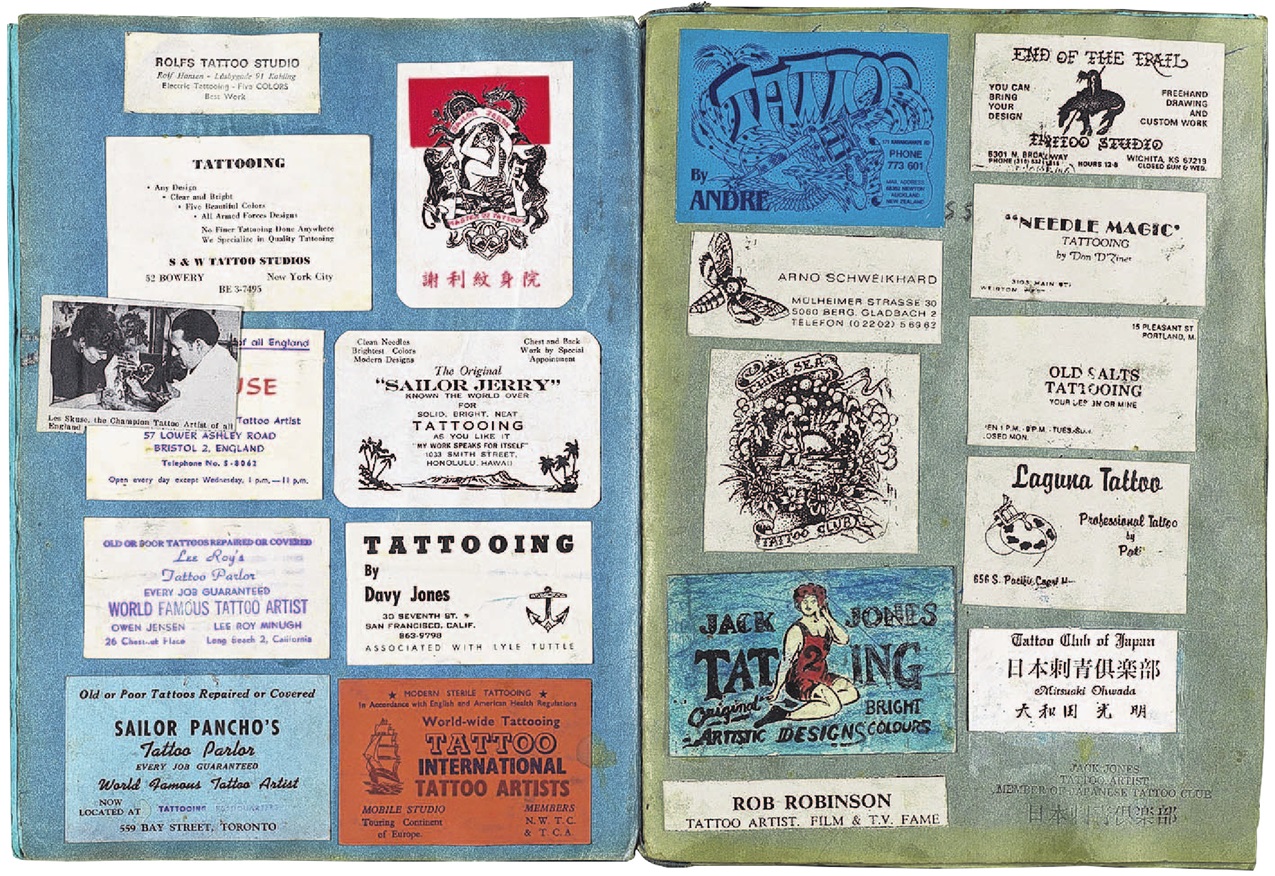

An intriguing aspect of the collection is Jones’ correspondence with others in the field. One scrapbook displays business cards ranging from the 1930s through to the 1980s, each card promoting an artist’s services from many places around the globe. He received mail and catalogues from artists as close as Dunedin and Melbourne, and as far away as Chicago, Copenhagen, Lausanne, Anchorage, Hong Kong and Hawai’i.

Jones exchanged letters most frequently with Bev Robinson, known in the tattoo world as Cindy Ray. Robinson was a prominent Melburnian tattoo artist and tattoo devotee who gained fame for the extent of her tattoos. Initially, Jones received her catalogues and newsletters (she sold tattoo and piercing equipment and promoted her business via newsletter), but eventually more personal letters were exchanged.

Safe practices were less prominent than today; in 1965 Robinson wrote to Jones saying that she had contracted "yellow jaundice" (likely Hepatitis B). There is little evidence in the papers of safety concerns, though, notably, many artists marketed their services as painless. Cover-ups and removals were also promoted.

We don’t know who Jones’ customers were, or how widely he marketed his skills. It seems likely word of mouth would have played a part, and perhaps the nearby port at Bluff provided a stream of seafarers looking for a way to fill their hours ashore. A Southland Times feature article, published only a few months before his death, reveals his preference for tattooing images of butterflies and mermaids, and his frustration with the trend at the time for "wicked toothy things".

Despite his disdain for gruesome designs, he had success with one in particular; a depiction of a skeleton wearing a red dress and carrying a handbag was very popular. It was common in the industry to share and sell flash designs with overseas artists, and a renowned British artist reported to Jones that the adorned skeleton was the most frequently requested piece in his studio.

The Jones collection abounds with his designs. These range from the expected anchors, hearts, roses, and partially dressed women, to crude stereotyped depictions of Māori and American First Nations peoples that would today be viewed very dimly. Small flash pieces were the norm, unlike today, where custom designed full sleeves and large chest tattoos prevail.

Jones was particularly drawn to Japanese tattooing styles, and by submitting copies of his designs he eventually gained life membership of the Japan Tattoo Club. Jones’ name also appeared in the members lists of the Bristol Tattooing Club and the Japan Tattoo Art Association — likely cementing him as one of the most globally connected Southland farmers of the 20th century.

To view the Jones collection and find inspiration for your next tattoo, visit Hocken Tuesday-Saturday, 10am-5pm. Free public tours are available on Thursdays at 11am.

Kari Wilson-Allan is a collections assistant at Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena.

![‘‘Neil’s Dandelion Coffee’’. [1910s-1930s?]. EPH-0179-HD-A/167, EPHEMERA COLLECTION, HOCKEN...](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/slideshow/node-3436487/2025/09/neils_dandelion_coffee.jpg?itok=fL42xLQ3)