WHAT IS AN EMISSIONS TRADING SCHEME?

An emissions trading scheme in its simplest form is a cap-and-trade scheme. The Government sets a cap on emissions, or the total supply of units available to the market and emitters must surrender one unit for every tonne of GHG they emit, and they can buy these in the market.

Some entities pollute less than the units they receive and can therefore sell the extra units in the market, while others emit more and may need to purchase units from the market. This sets the supply and demand, which in turn drives the price of these units.

The Government can control the supply in the market, by adjusting the rules of the game, ideally with a target of reducing emissions in line with our Paris Agreement obligations. The decreasing supply would lead to an increase in the price of the units and in turn push businesses to reduce emissions. One of the benefits of a market, in theory, is that those emitters that have the most efficient emission reduction options would implement those first.

THE NEW ZEALAND ETS SETTINGS

In New Zealand our system has various complexities, but three important differences to the simple cap-and-trade scheme described above are industrial allocation of units, the units earned for forestry carbon sequestration and historical and current artificial price ceilings.

Industrial allocation effectively gives a certain number of units to polluters for free (60% or 90%) if they meet certain eligibility criteria. The main reasoning for this is to address the issue of carbon-leakage, where polluting activities are moved overseas to avoid the carbon price.

Forestry sequestration generates units from post-1990 forests registered into the ETS as a reward for the carbon dioxide they sequester out of the air. For each tonne sequestered by registered forests the owners receive one unit.

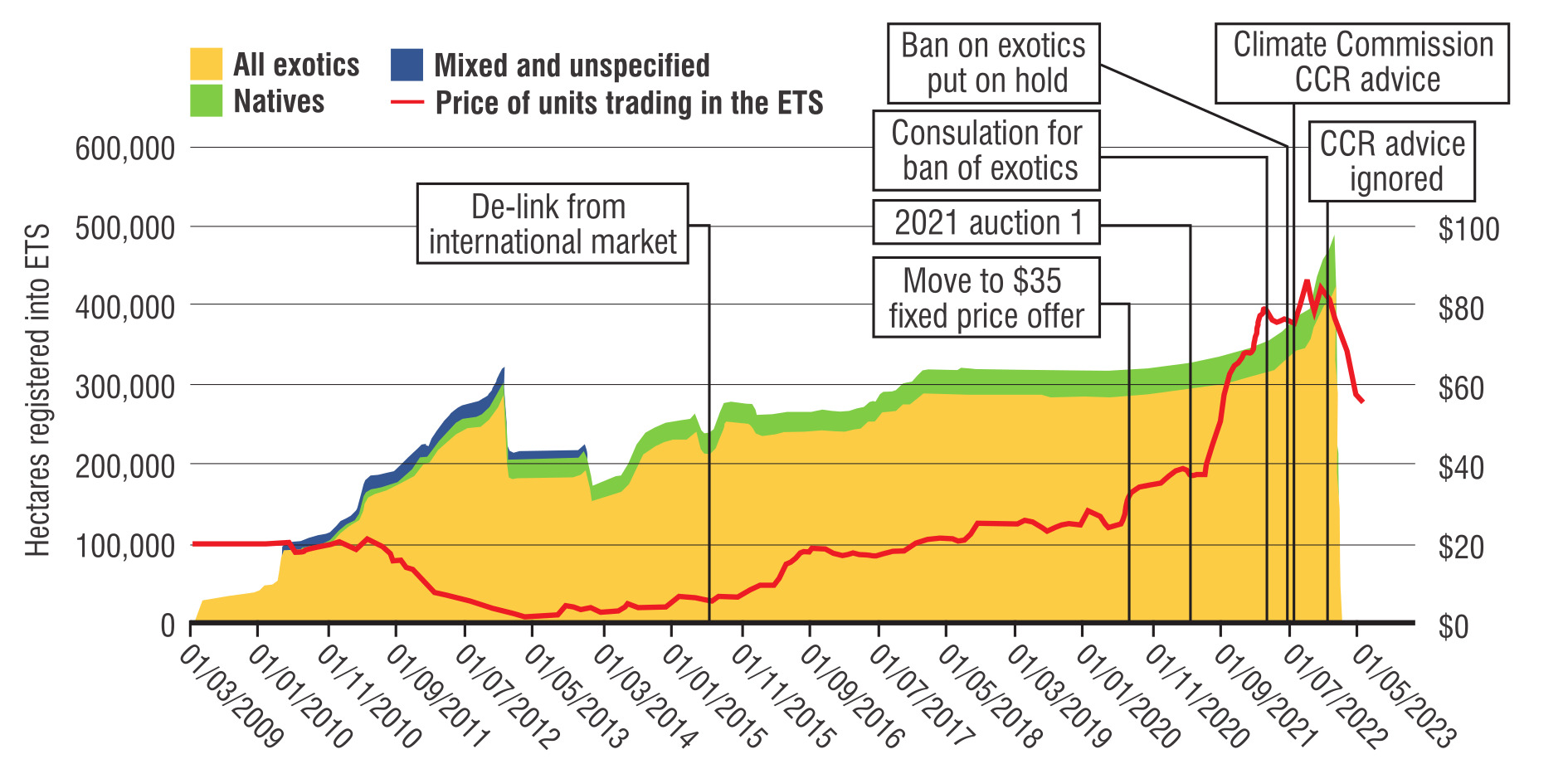

As we can see in the accompanying graphic, the ETS price (red line) has been increasing since the Government closed the scheme to international carbon markets in 2015, which operated under the Kyoto protocol but led to many poor-quality credits entering New Zealand (a stockpile that still hasn’t been resolved). However, the price only climbed to $25 as the Government was offering credits at that price, creating a price ceiling, and as soon as this was lifted to $35 in 2020 the market followed and reached this new ceiling. Then when the Government started to sell some credits at auction in 2021, rather than at these fixed prices, the price climbed again. However, the auction also has a Cost Containment Reserve (CCR) feature, which releases additional units at a certain price ($80.64 in 2023), effectively creating a price ceiling.

Remember, when the price climbs, the economic signal to reduce emissions strengthens and an increasing carbon price is an integral element to the Government’s own Emission Reduction Plan:

"By aligning with successive emissions budgets and expectations of an increasing emissions price, the NZ ETS supports flexible decision making — empowering businesses and individuals to make decisions that are appropriate for their unique situations." Chapter 5, New Zealand Emission Reduction Plan

WHY IS THE PRICE FALLING?

This author does not claim to have a crystal ball on why markets move but offers some potential explanations for the recent price plunge in the ETS.

Exotic forestry sequestration has become a hot topic as it can be quite profitable to plant Pinus radiata forests to earn carbon units. As the Government has been concerned about the potential side effects, last year they consulted on whether to ban exotic forests from the permanent forest category, for many reasons not discussed here. This was a rather blunt policy, ignoring approaches such as transition forests and continuous cover forestry, and was subsequently put on hold. However, we have seen a record area of exotic forest registered into the ETS in the past year, likely driven by the potential ban and historically high prices, far outstripping indigenous forest registrations, as you can see in the graphic.

Lastly, the Government is currently deciding on new eligibility criteria for the industrial allocation, which some commentators and experts believe will increase the number of credits given away for free.

So, the New Zealand ETS is certainly not operating under a cap-and-trade system as the only cap seems to be on the price and not on the supply of carbon credits or the emissions they represent. If the ETS is going to be effective, then the Government needs to hold true to its Emission Reduction Plan and listen to its own Climate Change Commission. Namely, New Zealand needs an ETS policy setting that limits the supply of units in line with the Paris Agreement, avoids giving credits to afforestation that exacerbates risks and allow the carbon price to increase if that is the effect of supply and demand balances.

The discussion of the 50% of NZ’s GHG that is not even priced in the ETS, namely agricultural emissions, is left for another day.

- Dr Sebastian Gehricke is a senior lecturer and director of the Climate and Energy Finance Group at the University of Otago. He is also a member of He Kaupapa Hononga: Otago's Climate Change Research Network.