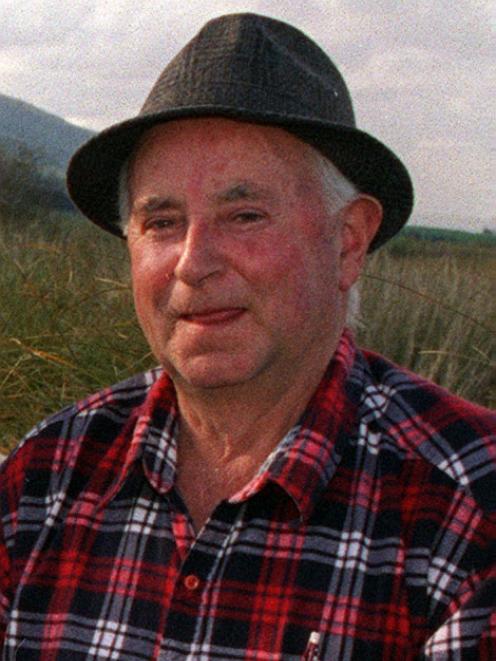

Horrie Sinclair’s bold personality and tenacity were vital in conserving Otago’s nationally significant Sinclair Wetlands, writes Helen Baker.

When you mention the name "Horrie Sinclair" to those who knew him there is immediately a pause, then a chuckle. Not easily forgotten, Horrie had a reputation for doing things his own way. He was a unique character and a passionate conservationist who spent his life preserving his wetland property at all costs.

He was also a keen duck hunter and undoubtedly, if he were still alive, he would have been joining the ranks of those heading out for the opening of the duck-shooting season this weekend. His nephew Barry Sinclair is among those who will travel out to Horrie’s old property, the Sinclair Wetlands, named in recognition of his contribution. Situated between Lake Waihola and Lake Waipori, on the Taieri Plain, the area is generally regarded as New Zealand’s largest privately owned wetland.

For Barry Sinclair, and other old friends of Horrie’s, what was an opportunity for duck shooting has become a tradition. Every year they travel out to the maze of secluded islands, swamplands and waterways that provide a home to 60 bird species and more than 100 native plant species. When the hunters arrive at the wetlands they stand at the jetty and toast Horrie and his brother Ian with a whisky and remember that without him they wouldn’t be there.

Horace "Horrie" Sinclair was born in Waitati in 1923 but lived most of his life on the Taieri. During his life he worked in a variety of jobs, including as chief ranger for the Otago Acclimatisation Society, forerunner to Fish & Game, and as a rabbiter for the Lee Stream Rabbit Board. Horrie bought the wetland property in 1960 for £2000 and knew from the outset that what he wanted was a place for wildlife to live and breed, and a place where he could hunt. He was vilified at the time for his determination to keep the 315ha block he purchased as a wetland but he looks to be on the right side of history. The Sinclair Wetlands (or alternatively Te Nohoaka o Tukiauau) are now a success story built on Horrie’s determination.

Wetlands were common in New Zealand prior to European contact. Various iwi including Waitaha, Kati Mamoe and Kai Tahu occupied the lower Taieri on a seasonal basis to access the rich variety of resources that could be found in the wetlands.

However, with the arrival of Europeans, particularly farmers, priorities changed. Swamps and wetlands were regarded as unhealthy by the new settlers, but they recognised the potential fertility of the land if drained. From the 1860s onwards much of the Taieri Plain was drained and the resources that iwi had relied on dwindled, causing the Kai Tahu settlement to move.

It is estimated that upwards of 85% of wetlands have disappeared since European settlement. The area that is now the Sinclair Wetlands was drained in the early 20th century and was used to grow grain. However, by the 1950s, the pumps had stopped and the area had begun reverting to its natural state as a wetland. Almost immediately following his acquisition of the land Horrie Sinclair was hounded by people wanting to buy it off him. From the start, Mr Sinclair’s stubbornness and strong beliefs served him and his wetlands well as he turned down offer after offer. His motto was "Without habitat we have nothing", on the basis of which he made the wetlands as his life’s work.

Mr Sinclair knew that all those who wanted to buy the land off him wanted it for farming and would drain the property again, destroying the habitat of the countless birds, fish and other animals that lived there.

"Horrie had people coming to him wanting to buy the wetlands and they wanted to convert it back to farmland and he said no ... he knew that they’d just convert it back into farmland," Barry Sinclair says.

He also had to do a lot of work to remove illegal hunters from his land who had been shooting there prior to him acquiring the land and were continuing to do so. A keen duck hunter himself, Horrie wanted to limit when hunting could occur and improve the wetland habitat in order to encourage the ducks to return in greater numbers. He took it upon himself to camp on Ram Island, in the centre of the wetlands, for 22 consecutive nights in order to bar the illegal hunters from his property. Looking back at the event some time later, Mr Sinclair told Country Calendar that "I was the most hated man in the Taieri at that time, that’s for sure".

Barry Sinclair recalls how "A lot of the time there was Horrie’s way or no way". However, it is also clear that Mr Sinclair was a kind man and his friends and family describe him as ‘‘generous to a fault’’ and someone who would do anything for a friend.

As a bachelor, Mr Sinclair did not have any immediate family but he was close to his brother Ian, who shot in the wetlands until he passed away, and Ian’s son Barry. Barry talks fondly of going out to the wetlands when he was growing up.

"We used to go out there all the time, and back then even the fishing was fantastic out there".

His friend and fellow duck hunter Lindsay Strong says Mr Sinclair was also good with children.

"When we used to go down there with the kids, Horrie always had a bottle of soft drink in the back of his Landrover ... there’d always be a soft drink out for the kids and either a biscuit or a chocolate bar or something like that."

For all that, Mr Sinclair liked doing things his own way and made some enemies as a result.

"If he’d allowed himself to be beaten down it wouldn’t have happened," Mr Strong says.

"He stood up for what he believed in and as a result we have the wetlands."

In the end, his efforts were widely recognised and Mr Sinlcair was awarded an MBE in 1986 and a 1990 Commemorative Medal, both for his services to conservation work. Hunting and conservation may not seem natural allies but many hunters recognise the importance of habitat and the need to maintain the environments where animals and birds live. Mr Sinclair himself held the view that hunters are in fact among the best conservationists because it is in their interests to preserve the habitat of the game they hunt. It was a view ahead of its time.

"For the first 20 years everyone thought I was mad. Conservation was a dirty word, and anyone who practised it had lost their marbles," he told the Taieri Herald in 1986.

Another point on which Mr Sinclair insisted was responsible hunting, which he achieved by limiting the number of days shooting in the season and personally selecting who could hunt on his land. Mr Strong recalls how "anyone who went over the limit would hear about it from Horrie and he’d have you off the property ASAP". Mr Sinclair also argued, in defence of hunting, in the 1980s that "If you don’t shoot the game birds they’ll die of starvation. You must harvest them like a crop."

The change from cropping to dairy farming in the Taieri area had reduced the amount of food available to mallard ducks, he said.

Mr Sinclair owned the property until 1984 when he gifted it to the New Zealand branch of the international conservation organisation Ducks Unlimited and it was placed under an open space covenant for protection. As a condition of this gift a complex including an education centre and accommodation was built overlooking the wetlands. Mr Sinclair remained on site as manager of the wetlands until his death in 1998.

The wetlands were gifted back the same year to Kai Tahu as part of their Treaty of Waitangi settlement with the Crown and today they are generally regarded as New Zealand’s largest privately owned wetlands.

The current co-ordinator of the Sinclair Wetlands, Glen Riley, is also passionate about protection of the habitat. He works with schools and other volunteer groups who help with conservation work around the wetland.

"Our number one priority is mahinga kai so we’re trying to make it abundant and amazing and useable. It’s like any conservation site, the difference is the end goal. It is to be able to use it again so it’s not just to stand back and watch, it’s to actually hands-on be involved in harvesting and collecting resources like people used to," Mr Riley says.

It is possible to make a link between Horrie Sinclair’s focus on sustaining the habitat for duck hunting and the goals of Kai Tahu to be able to use the resources that the wetlands provide in a sustainable way. According to Mr Riley, while the wetlands are a home to many species, "it’s also for people and we’ve got to maintain that connection with people and land".

While the wetlands can never be exactly the same as before it was drained it is possible to adapt and use the landscape that is now available, he says.

Today, New Zealand has few wetlands left, which makes those that remain even more important. Mr Riley says wetlands are responsible for water quality by acting as a filter.

"They’re also really important for preventing flooding and erosion as wetlands act like a sponge ... wetlands gently soak the water up and then slowly release it back out to sea eventually. Take away the wetlands and all that water is gushing and screaming through."

Wetlands are also important as a place for outdoor recreation and can be culturally significant as a mahinga kai site. It is only recently that there has been increased recognition of the place of wetlands in the environment, underlining the foresight in Mr Sinclair’s conservation efforts.

It seems certain that Mr Sinclair would have been delighted with the effort that Mr Riley and others are are putting into maintaining the wetlands that he loved. Duck shooting continues there as part of Mr Sinclair’s legacy, and the future should see increased opportunity for Kai Tahu to use the area for mahinga kai again. A wander around the wetlands reveals the abundant wildlife they support. Further reason to raise a glass to the single-minded Horrie Sinclair.

- Helen Baker is a University of Otago humanities intern at the Otago Daily Times.