It was a sunny autumn day in 1956 when 10-year-old Graeme Rice was heading home, pushing his bike over the busy Ravensbourne railway footbridge on the edge of Otago Harbour.

On his back was a bag full of pears picked at his aunt’s property. Daydreaming, the young Rice stepped off the footbridge on to the State Highway 88 pedestrian crossing.

"I remember hearing cries and yells but thought nothing of it until there was a fearsome bang and my body, bike and bag of pears thudded down on to the road," Rice recalls.

The bag got hooked on the front bumper of the car that had hit him and Rice was dragged past shops where the Ravensbourne Hotel now stands.

"It’s incredibly noisy under a car, but I experienced a surprising degree of detachment.

"I watched as my right leg was pushed along with the wheel of the car rubbing it, leaving a painful burn.

"Then it started to go over my knee and I hoped the car would stop before my knee was run over."

When the car did halt, a crowd gathered and the local newsagent tried to pull Rice from under the vehicle. Others attempted to stop the car driver from hurriedly drinking milk to mask the alcohol on his breath.

Only a couple of months earlier, Department of Transport inspector Jack Henderson had stood in front of the Ravensbourne School assembly and predicted that at least one of the children would be run over before Christmas.

Then, the headmaster raised the school safety flag, which would fly until someone from the school was involved in a car crash.

"There it proudly flapped until that afternoon when I stepped in front of a 1928 Chrysler Plymouth."

It is the sort of first-hand experience no-one wants. But it proved seminal for someone who would spend 46 years in road safety roles, beginning as the Ministry of Transport’s road traffic instructor, in Oamaru, and finishing last week as New Zealand Transport Agency’s regional safety investment adviser.

He has been pleased to see the road toll drop over time, but says significant change is still needed to make roads safer for everyone.

Being run over became a childhood memory. Rice completed high school, became a signwriter and display artist then volunteered for National Military Service, where he was assigned to the armoured vehicle corps.

By 1974, back on "civvy street" and married to Kate, with a second child on the way, Rice was disillusioned with retail art. The memory of that accident came back strongly when he saw a road traffic instructor job advertised.

It sounded like a fulfilling role, and an interesting one for someone who even as a 6-year-old had been able to name the makes, models and years of all the cars on his street.

But when told, on the quiet, that he was up against two local traffic officers, he phoned to withdraw his job application.

Do not be hasty, one of the interview panel members cautioned.

The interviewers had spotted Rice’s handiwork, posters advertising jackets, in the front window of the department store where he worked.

"And, oh," the interviewer added, "the last thing we need for this new role is a tired old traffic cop who will just want to tell kids what to do and issue tickets."

Little did Rice know, road safety would be a vocation he would still be pursuing more than four and a-half decades later.

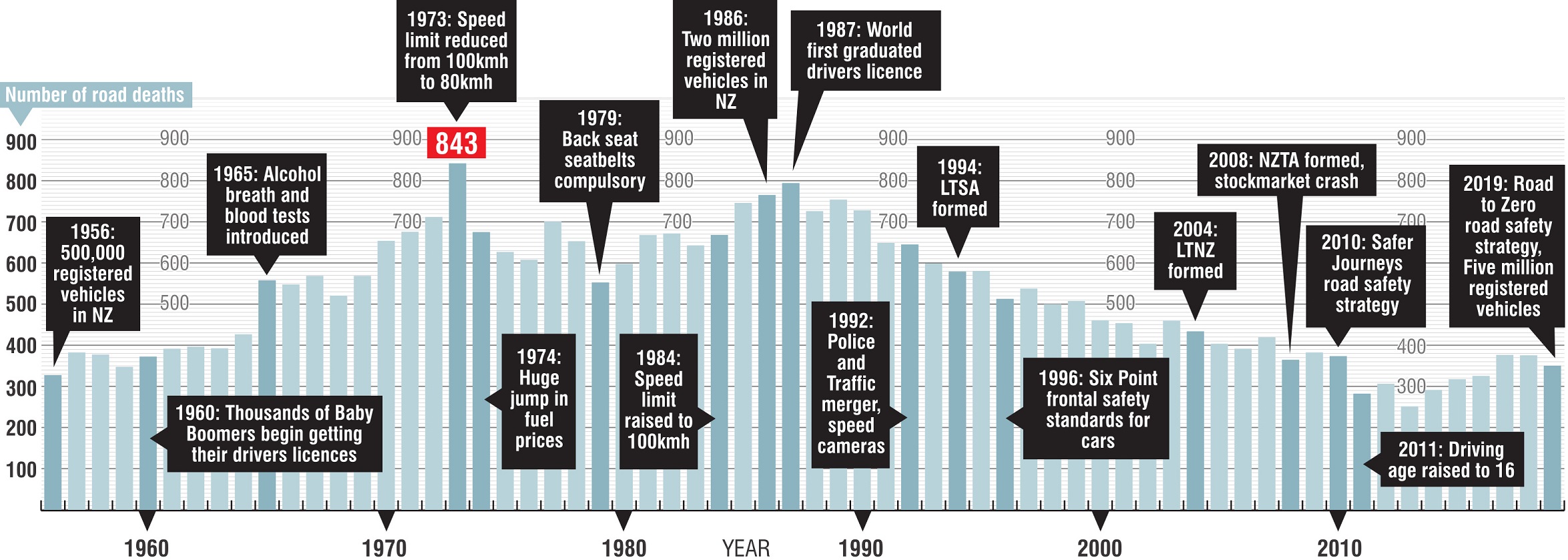

That year, 1974, was a tipping point for the country’s road toll. The previous year, New Zealand had hit a horrendous all time high of 843 deaths on the road.

Since then, although there have been fluctuations, it has had a downward trend, albeit with a lingering and persistent tail. Last year, despite the population being 60% higher than in 1973 and the number of registered vehicles four-fold greater (now 5.4million), the road toll was 58% lower at 352.

"The safe system approach recognises humans are frail and cannot withstand the forces and impacts generated in a crash," Rice explains.

It also accounts for the reality that not everybody drives carefully, soberly, lawfully and attentively all the time.

"It is in these moments that the safe vehicle, the safe speed, the safe roads and roadside and the safe driver might make the crash survivable rather than fatal or serious."

The decades have been sprinkled with excitement. In the early years, when the role included wearing a uniform and doing some traffic enforcement, his elevated pulse could be due in equal measures to fear and bravado.

Once, officials tried to nominate Rice for a bravery citation when he stopped and chatted with the driver of a stolen vehicle until police arrived. Rice felt he could not accept the nomination because he had acted in ignorance, having left his patrol car before the call came through warning the driver was dangerous.

He found the car and pulled it over. The driver was pleasant and Rice started to give him and the passenger a "telling off".

The passenger responded by picking up a .22 rifle and pointing it at Rice.

"The only thing I could think to do was to appeal to the driver’s good sense, reminding him that right now he was facing a telling-off and at worst a charge of reckless driving but if his mate pulled the trigger, he was going to jail for at least 10 years.

"Immediately the driver turned to his passenger and punched him squarely in the face.

"Looking brave from the waist up, I suggested the driver get his passenger home and dump him.

"From the waist down, my legs were rapidly turning to jelly."

From a standing start as a road traffic instructor, in North Otago, Rice progressed during the next two decades to traffic education and road user standards officer for the region and then district manager for the Ministry of Transport, based in Dunedin. Towards the end of that time, he also served for five years on the Automobile Association national executive. As well as setting up a driver upskilling programme and ensuring high standards for driver training, Rice took the lead creating a government-industry partnership that produced Drive Plan 20 driver education videos used in schools nationwide.

In 1990, a Lee Bell came into the Ministry of Transport (MOT) offices in Dunedin demanding to know what staff were going to do about what she said were defective and dangerous bicycles being sold here.

The Dong Fang bikes were imported from China and were being incorrectly advertised as MOT-approved, Rice says.

"They looked very attractive, but unfortunately the workmanship on them was hugely variable," Rice, who still has one of the pint-sized bikes, says.

"Not all, but many of them fell apart at the slightest bump or jolt. Tyres went flat. Handlebars broke off. Pedals shattered. Brake levers bent under pressure applied by children. Welding at various points in the frame gave way.

"We were getting injuries."

Rice was charged with investigating and sorting the issue.

Allied Press community newspaper The Star took up the cause.

The fledgling Commerce Commission got involved, taking a legal case against the importer, one of the first under the 1986 Act.

"I felt sorry for the guy, the importer ... I think he had put a lot of his own money into this venture. And suddenly it was going very pear-shaped.

"I don’t care who you are, if you do something in good faith, thinking it’s OK, then that’s sad."

The MOT was a behemoth whose roles included traffic enforcement, air traffic control, weather forecasting, air accident investigation and lighthouses. During a six-year period, starting in 1988, it was chopped into several chunks. In 1992, the MOT’s 1000 traffic cops were merged with the 6000-strong New Zealand Police.

That enabled then minister of police John Banks to say he had delivered on a promise of an extra 1000 police and Minister of Transport Rob Storey to claim the road toll would drop dramatically now that there would be an additional 6000 traffic officers on the roads.

In practice, the transition was not smooth, Rice, who remained with the MOT, says.

"For a considerable post-merger period, there wasn’t very much traffic enforcement being done at all."

At about the same time, Rice temporarily became an object of hate for many motorcyclists. After being subjected to deliberately irritating and reckless driving by a group of motorcyclists, he had written an opinion piece in the newspaper. In essence the piece asked "Why is it that motorcycles are still allowed to be made?"

The reaction from the biking fraternity was extremely hot and equally bothered.

Rice wrote a follow-up using motorcycle injury statistics to show how much more vulnerable riders were than drivers.

He was threatened with a lawsuit by a motorcycle retailer and asked to attend a "small" meeting of Otago motorcyclists.

"There were hundreds of angry people. I just had to get up and say, well, these are the risks if you ride a motorbike."

The reshaping of New Zealand’s government transport sector continued. Rice rode the turbulent current of restructures and mergers. The entity he worked for was named the MOT, then the Land Transport Safety Authority, Land Transport New Zealand and finally, in 2008, the New Zealand Transport Agency.

For the past decade, he has been the regional safety investment adviser, liaising with local and central government to ensure road safety projects are safe, give value for money and meet the needs of society and commerce.

The focus of roading policy has fluctuated, depending on who is in government, between sustainable travel and economic imperatives.

"We need to ditch, once and for all, the mantra of ‘efficiency over safety’," he says forcefully.

"The very idea that a number of deaths and serious injuries should be tolerated just so commerce can benefit from rapid vehicle movements is so wrong."

Rice’s last day at work was yesterday. Retirement plans include getting back to neglected art projects and doing some more writing — about cars and for grandchildren. He also has a couple of boats and some cars that need time spent with, and on, them.

"But I’ll probably end up doing vacuuming and mowing the lawn," he says with a laugh.

Roads and road safety, however, are unlikely to be far from his thoughts.

A pressing need, Rice says, is a conversation about how inner-city streets are apportioned to different users.

"I think we are facing a carriageway crisis," he says.

"We have a lot more vehicles of different sorts wanting to access the same road space. And they can’t all go on the footpath.

"I’m talking e-scooters, motorised skateboards, hoverboards, e-bikes ...

"People say cyclists shouldn’t go on roads. Well, who said the car was the only thing allowed on the road?

"Pedestrians also need space and need to feel secure getting to the places they need to access. Whereas, right now, inside a car is probably the only place you can feel safe in the CBD.

"These are all questions we have to address."

He can see two potential solutions — removing the kerb and channelling between footpath and roadway so the entire carriageway becomes a shared space; or, expanding the footpath by taking out a traffic lane and restricting the number of vehicles allowed in the area.

"We’ve got to realise the demographics are changing. Not everyone wants to drive everywhere all the time. And then we need to build a road safety programme on the back of that."