The deadly Libyan dam failure this year has brought dam safety to global attention.

Mary Williams reports on Otago’s often hidden, and really old, large irrigation dams and imminent safety regulations around them.

All big dams in Otago will come under the spotlight of new safety rules next May, raising some obvious questions.

Will the rules expose unsafe dams?

If so, will they be mended, replaced or just torn down - and who would pay?

Most importantly, are people and property at risk, now?

Some of the region’s old, big dams are past their 100th birthday and owned privately by irrigating farmers and other locals who use the water.

These dams are not restraining ponds in paddocks. Some were built to hold maximum reservoir capacities of millions of cubic metres.

One is nearly the same size as the Roxburgh hydroelectric dam spanning the Clutha River.

Roxburgh, Clyde and Hawea - all managed by energy giant Contact - are all younger than the old irrigator dams.

Old dams were inevitably built to the standards of the time, without modern knowledge of seismic or climate impacts.

That much is known, along with the adage nothing lasts forever.

An old dam can fail for one or more reasons - inadequate or defective construction, any deterioration, or the two big natural hazards - earthquakes and big rain events.

Otago dam engineer Brendan Sheehan says there is a ‘‘wee bit of an unknown out there’’, with the state of the dams, given those that built them did not have the knowledge we do now.

Old dams “need to be looked after like a grandmother - with care’’, he says.

They might not fall over tomorrow, but owners will “need to make a decision about what to do’’.

Dam engineers - who work for dam owners - are not prepared to say much more.

What is on the cards?

Evidence of dams’ standards is not in the public domain, yet.

The Dam Safety Regulations 2022 will require all dam owners to hire a specially-certified engineer to classify their dams as low, medium or high “potential impact” in the event of a failure, and submit this classification within three months to their regional council.

A year after that, owners of dams that are high potential impact must have submitted a ‘‘safety assurance programme’’ to their regional council.

Owners of medium potential impact have two years to do it. Low-impact dam owners do not have to do it.

Councils can enforce any non-compliance and dam owners are also required to keep reviewing, to a schedule, impact classifications and safety programmes for dams in their region.

New Zealand is one of the final members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development to introduce such rules.

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) recognises this lateness has “posed a risk to people, property and the environment’’.

In a press release about it, building policy manager Amy Moorhead says the rules will reduce the likelihood of dam failures that have the potential to cause significant harm a great distance downstream.

What exactly are we dealing with?

There has been a serious dam incident in New Zealand every five years since 1960.

People leapt to safety when the partially built Opuha Dam in South Canterbury unleashed about 13 million cu m of water in 1997.

Andrew Crofoot, Federated Farmers dam safety spokesperson and Wairarapa farmer, laughs wryly at how long it has taken to get rules in place. He spent years on technical committees preparing the new rules.

At one point things “got ridiculously restrictive and would have required reporting on every dam, which was absurd’’, he says.

His farm has about 100 small stockwater dams. A bigger size limit was negotiated.

The new rules apply to dams one metre or higher that store 40,000 or more cubic metres of water, or dams four metres or higher that store 20,000 or more cubic metres.

It is estimated about a third of known dams will fall within the rules.

The lack of regulation to date means there is only sketchy national dam data.

A 2013 study by MBIE and the Ministry for the Environment managed to add 2048 dams to the New Zealand Inventory of Dams, bringing its total to 3284.

However, reservoir volumes were recorded as ‘‘unknown’’ for nearly half.

Some dams may remain hidden.

Otago Regional Council compliance manager Tami Sargeant says a list of the region’s dams and their status cannot be supplied as the work is ongoing.

Some of the oldest dammed Otago reservoirs are out of sight, accessed up bumpy, long tracks travelled by farmers, dam managers and anglers.

The damage if they burst is the subject of flood mapping and dependent on water in their reservoirs.

Silt deposits can also reduce capacity. Their operation to date has not been entirely without legal constraint.

The Building Act 2004 enabled councils to take action if a dangerous dam was reported, but no dangerous dams have been flagged by owners to Otago Regional Council (ORC).

Dam owners also have access to extensive guidelines about how to manage dams safely, from the New Zealand Society on Large Dams (NZSold).

A dam’s safety management requires hazard assessment, monitoring for damage or movement, and remedial action to address identified risks.

The ORC is getting ready for the new regulations by consulting the public on a review of its dam safety policy, which explains its oversight remit.

This has prompted questions from regional councillor Michael Laws about dam numbers and dangerous dams.

In an internal exchange, Cr Kate Wilson responded ‘‘it would be problematic’’ if ORC had to find dams and do the engineer-certified reports.

It could also be problematic for dam owners to commission the reports in time.

As of this month, there are only 13 engineers approved by Engineering New Zealand to do the work.

More are likely to be approved, but it is taking time.

What are these dams like?

Not all Otago’s irrigation dams are old.

The Loganburn Dam was built in 1983.

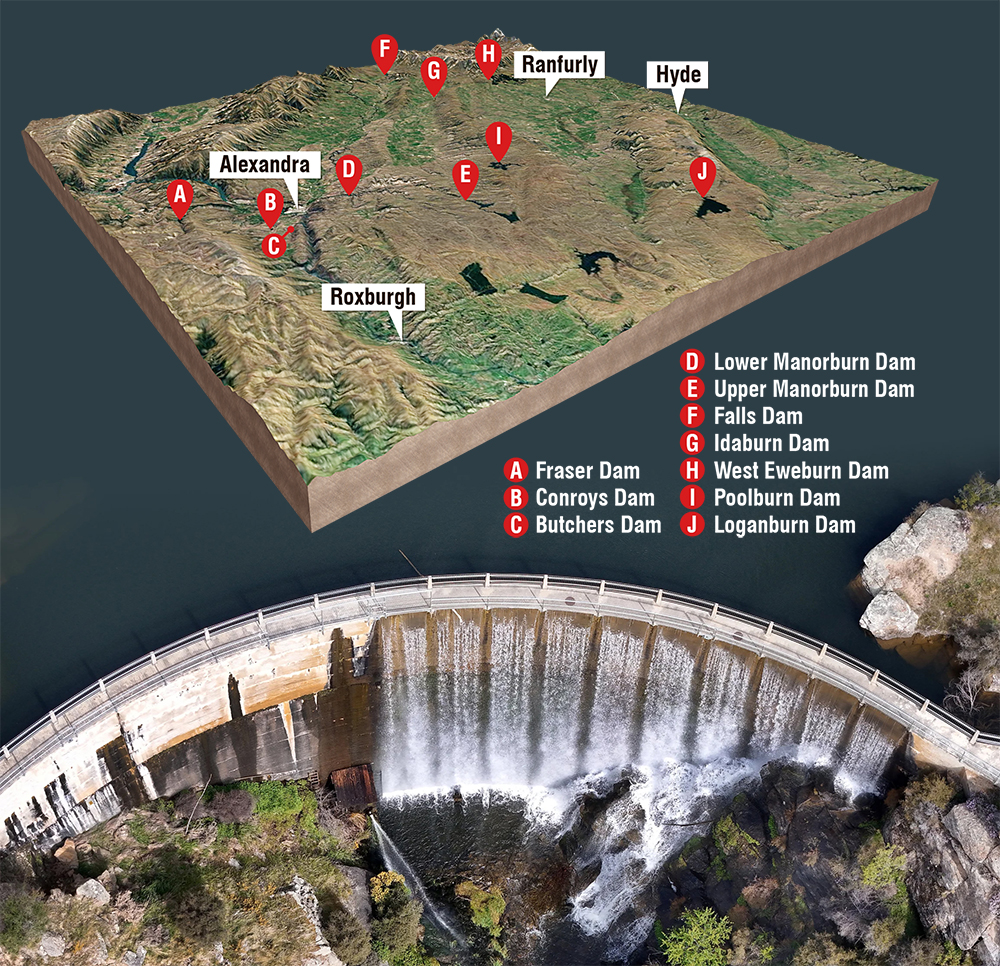

However, at least nine, old irrigation dams sit to the north, east and south of Alexandra - Falls, Upper Manorburn, Poolburn, Lower Manorburn, Conroys, Butchers, West Eweburn, Idaburn and Fraser.

These old dams were transferred from government ownership to irrigating landowners around 1990.

Two - Falls and Fraser - also help to generate some hydroelectric power.

Falls Dam was built in 1935 with a 10 million cu m capacity. Poolburn, built in 1931, has a 26 million cu m capacity. Upper Manorburn, built in 1914, is even bigger, with a 55 million cu m capacity, nearly as big as Roxburgh hydroelectric dam, which has a capacity of 65 million cu m.

An engineering report into all nine dams was commissioned by the Government back in 2000.

The report, by consultancy Opus, took a fascinating dive into the dams’ construction, defects observed back then, and the ownership transfer.

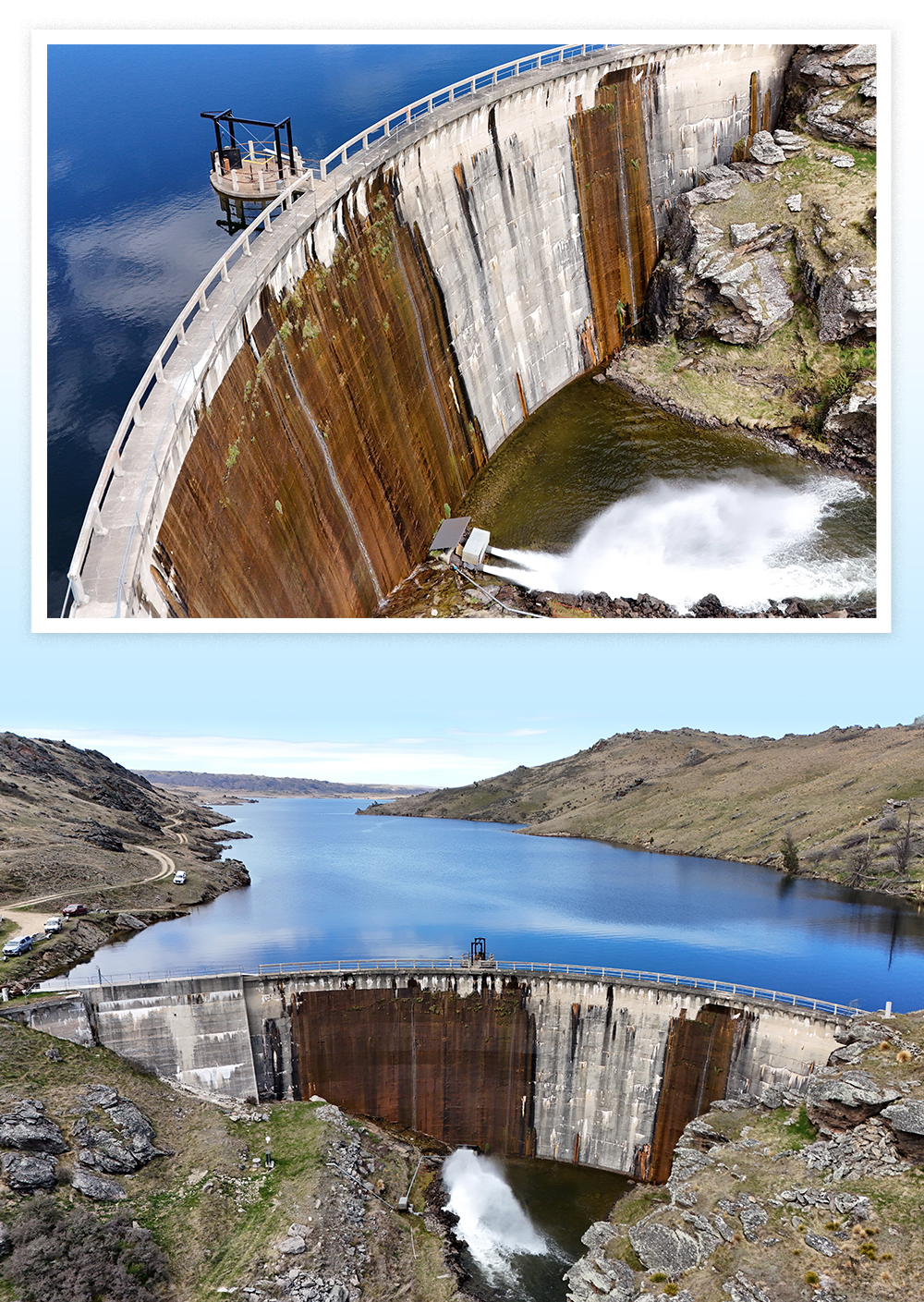

Falls Dam is rock-filled.

Modern construction requires rock-filled dams to be compacted in layers.

Falls Dam is uncompacted.

Eweburn is an earth dam and the other seven are concrete “arch” dams.

Five of these are “thin arch” and Upper Manorburn and Poolburn have thicker arches.

The report listed aspects of deterioration and the dams “generally fall short” of current design standards, it said.

This was “particularly evident in the degree of seismic resistance’’.

Seismologist Professor Mark Stirling, University of Otago earthquake science chair, has advised Contact and praises dam owners who have followed the NZSold guidelines, including incorporating seismic hazard uncertainty into dam assessments.

This requires a “tonne of work” that can “significantly increase the cost of the assessment”.

GNS Science principal scientist Matt Gersenberger leads New Zealand’s seismic hazard modelling, available to government and industry to estimate quake impact.

He says an understanding of seismic hazard modelling is a “critical input into risk-based decision making” to assure a “robust future”.

Identified elevated risk then needs tackling, he says.

What will the new rules mean for dams, and their owners?

Contact’s dam manager Peter Silvester, a member of the NZSold committee, has seen the process of drafting the new regulations through - from seismic hazard assessment to remedial work.

He says the new rules are “aimed at all dams – but not necessarily targeted at those with safety programmes like ours. The regulations will capture other dams’’.

Which these ‘‘other dams’’ are, and their safety standards, remains unclear - along with any major remedial actions that could be required.

A programme of renovation could require draining a dam to address defects below the water line.

This puts a dam out of action for a time.

Alternately, dependent on terrain and permissions, a dam could be drained into a new, lower reservoir, contained by a new dam.

Both options present an opportunity to alter dam size and reservoir capacity.

A third option is to decommission, by fully or partly emptying a dam. In California, some dams are being destroyed to restore the environment.

Options one and two carry a cost. Option three impacts water use and farming practices.

Urban design specialist at the University of Auckland, Professor Diane Brand, used to work for Ministry of Works and bemoans the shifting of dam ownership from public to private.

“Anything that is essential to public health and safety surely has to be in public ownership.”

The 2000 Opus report about the Otago irrigator dams includes a revelation.

The government’s sale and purchase agreements, with the exception of the Fraser dam agreement, included “return clauses” offering to buy back the dams into public ownership “in the event of dam safety legislation being introduced and compliance being shown to be uneconomic for the new owners’’.

“Dam safety evaluation studies undertaken prior to sale revealed deficiencies which could affect future viability”.

In short, the government knew it was passing on ageing, proverbial lemons to the private sector.

There was a catch - most clauses expired around the millennium, the report said.

The imperative of the private owners having a savings plan, or access to bank loans, for any required major overhauls or replacement of old dams, is written as large as a dam wall.

‘Old man’ dam still on engineers’ minds

A retired engineer who used to live downstream of the 88-year-old Falls Dam is surprised issues identified with the dam in 2014 may still not have not been resolved.

Mary Williams reports.

Falls dam is an ‘‘old man’’ hidden above a gorge at the Manuherikia River headwaters.

It is out of sight, but not out of dam engineers’ minds. Engineering reports have listed various defects as the dam has aged.

One report, by Golder Associates in 2014, discussed defects in the context of the dam’s future - a possible raising or replacing of the dam.

A replacement dam was the practical solution to accommodate ‘‘the high seismic loads required for design’’, it said.

The dam is close to the Blue Lake fault and a replacement dam was the practical solution to accommodate ‘‘the high seismic loads required for design’’, it said.

Retired engineer Steve Tilleyshort used to own a lifestyle block in the Manuherikia Valley and attended irrigator meetings prior to 2014.

He said even then he was ‘‘left with the impression there were major concerns about the dam’s safety and liability and that a solution had to be found. I haven’t heard that this has been resolved’’.

‘‘There is concern about protecting fish in the river, but what about people’s safety?’’

Site visits by Golder for its 2014 report revealed ‘‘deterioration, cracking, pitting, and erosion of the concrete liner’’ of the dam.

It noted other defects including in the spillway, the reservoir’s giant plug hole.

Some repairs, recommended in 1989, were still outstanding in 2014, it said.

Omakau fire chief Lloyd Harris described the dam as ‘‘an old man’’, but he did not think much harm would be caused if the existing dam broke.

The Manuherikia Community Response Plan, by Emergency Management Otago, contains a map suggesting a dam break flood would not reach the communities of Omakau and Ophir, and the dam’s maximum capacity is likely diminished by a percentage due to silting, a natural occurrence mentioned by Golder.

One thing is certain, however - the dam keeps getting older.

Since 1990, for more than a third of its life, Falls dam has been owned by local irrigators.

The government paid them to take it.

The dam and its irrigation distribution systems were sold to irrigators for $0, who also received $450,281 for ‘‘liabilities of completed schemes’’ and ‘‘water rates revenue refunded’’.

The agreement had a buy-back clause in the event of safety legislation affecting the viability of the scheme. This expired in 1999.

Since the ‘‘sale’’, the irrigators have had 33 years to plan the dam’s future.

Some of the biggest shareholders are now dairy farms, particularly reliant on water.

About 70 people attended a meeting about the dam in Omakau in 2014 at which the estimated costs of increasing the dam’s capacity was discussed as ranging from $70 million to a whopping $194m.

A bigger Falls dam could help meet irrigators’ needs plus leave more water in the river - but would still need funding.

Central Otago Environment Society secretary Matt Sole says he would be ‘‘wary’’ about dam owners using safety as ‘‘leverage for community or government funding for dam replacement, when dams bring ecological negative consequences’’.

He supports farming undertaken within environmental constraints and would welcome the dam’s removal.

Ian Walsh, technical principal of engineering consultancy WSP, helped write the NZSOLD dam safety guidelines and provided consultancy to Falls dam owners.

He says there was not an expectation that older dams, even in good condition, would comply with modern dam construction standards.

‘‘By definition there will be a deficiency present that has to be managed, by various techniques.’’

Falls dam chairman Murray Heckler was interviewed by the Otago Daily Times earlier this year about the ORC draft plans to leave more water in the river.

At that time, he said he did not know what a bigger dam would cost now - and said it ‘‘could be prohibitive for the irrigators to fund a new dam’’.

He said it could be a ‘‘very hard ask’’ of irrigators, particularly if it would not irrigate more land.

Interviewed again for this article, Mr Heckler says he had more ‘‘up to date’’ safety reports than the Golder report but declined to share them, or answer questions about what remedial repairs had been undertaken to address safety issues raised in older reports.

The dam’s owners are ‘‘investing time and money in working through the recommendations’’ of a dam safety review and ‘‘working to ensure that we can comply’’ with the new rules, he says.

Risk management includes a daily review of water levels and monitoring data, monthly inspections, ‘‘deformation’’ surveys and emergency planning.

‘‘Our people are very aware of their responsibilities as they live in the community downstream.’’