James Macandrew played an important role in the making of Dunedin, Otago and New Zealand. But he has had no biographer until now.

The following extract from R.J. Bunce's new book Slippery Jim or Patriotic Statesman: James Macandrew of Otago throws a spotlight on this admirable, important, yet notorious figure.

On a mild summer's day in January 1851, 31-year-old Scotsman James Macandrew disembarked from a barge on to Dunedin's manuka jetty at the head of Otago Harbour in search of lodgings for his family members, who awaited him aboard the schooner Titan, at Port Chalmers.

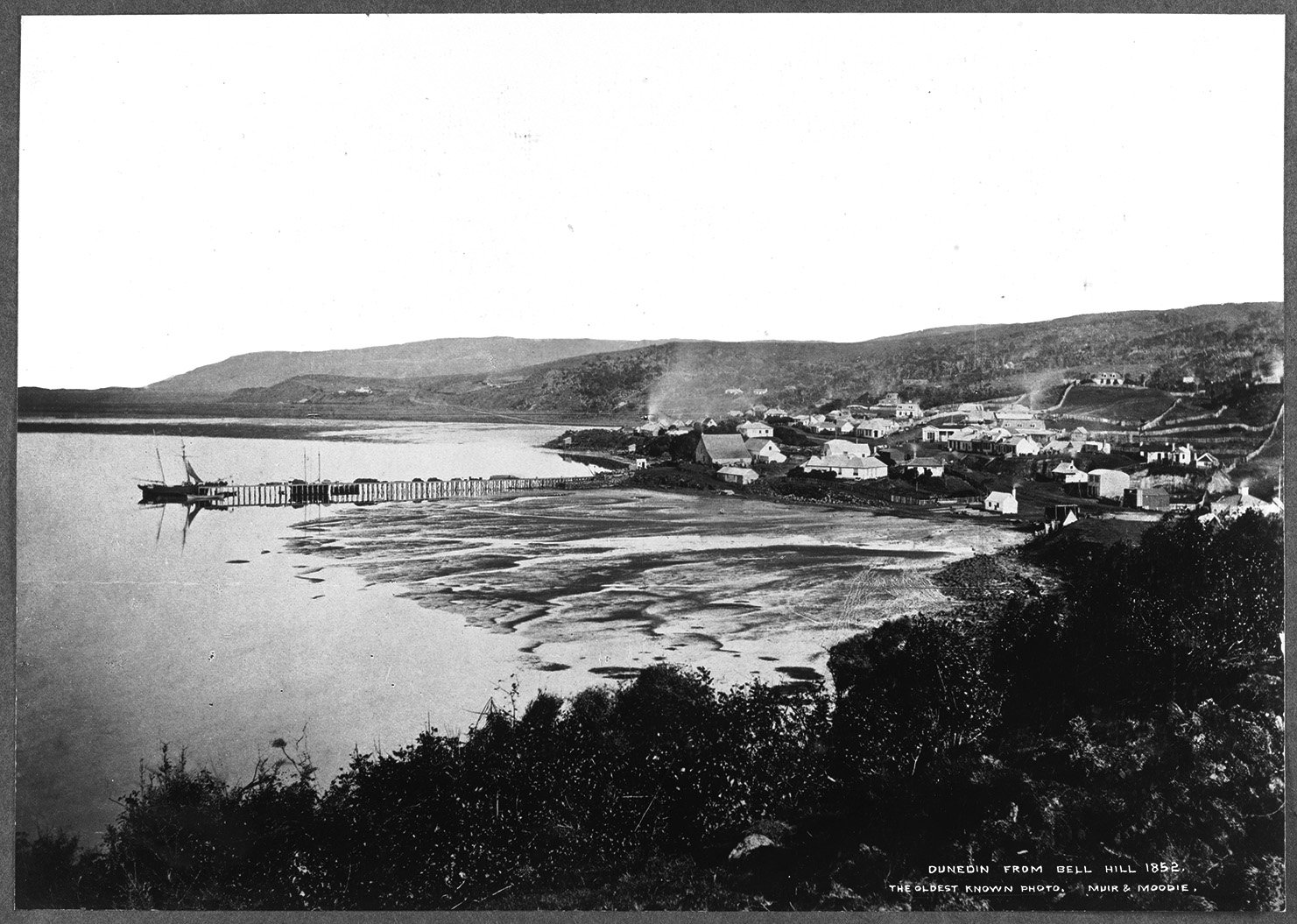

The jetty stood between the muddy strip at the mouth of Toitu Stream, where the first Scottish settlers had landed in 1848, and a ribbon of strand where local Maori beached their waka. The houses, hotels and businesses of the three-year-old settlement, home to some 1400 people, straggled along the shoreline over waterlogged land striped with ridges and gullies and enclosed by a circle of hills crowned with "an irregular crescent of reserve", the distinctive Town Belt. A Presbyterian manse occupied the land to the left of the wharf; to the right a church and a schoolhouse stood at the bottom of a steep hill, beyond which lay the flat northern reaches of the town.

A short walk up Jetty St led Macandrew to Princes St, the settlement's main thoroughfare. This ran south to a tidal inlet, later reclaimed as the Market Reserve, and to the north spanned Toitu Stream, scaled Bell Hill and crossed Moray Pl and its central reserve (later known as the Octagon). Here it was renamed George St and continued through swampy ground to a river known as the Water of Leith. Several stores, a smithy and a number of hotels were clustered on Princes St beneath Bell Hill and cottages dotted the slopes above; few buildings had been erected to the north of the hill. The streets were muddy, the bogs were foul with sewage and the streams were tainted.

This unprepossessing village would be the base for Macandrew's spectacular business and political careers, and he would be involved in many aspects of its meteoric growth. By the time of his death in a carriage accident in 1887, Dunedin would have 45,514 European residents and would be the second city of New Zealand, its streets paved by the gold extracted from the hinterland. It would boast substantial civic buildings, stone churches, the country's first university, factories, steam trams, a cable car to the spreading hill suburbs and a ferry service to the harbour-side settlements.

James Macandrew (1819-87) had arrived in the land of his dreams. He was welcomed as a successful and wealthy Scottish entrepreneur, his reputation enhanced by business experience acquired in London and by the fact that he had arrived on his own ship. His life over the next four decades is a remarkable tale of unwavering faith in his own judgement, challenges to the established order, risk-taking, undreamed of financial success and utter failure, and a determination to shape the new colony in his own image. He was the very model of the "merchant adventurer, [the] commercial entrepreneur" - the sort of man who helped to build the British Empire.

Few people today know of James Macandrew, yet for 36 years from 1851 there was scarcely a day when he did not feature, for reasons both admirable and notorious, in one of New Zealand's many newspapers. His political career spanned three unique periods of New Zealand's history: he was directly involved with the establishment of self-government, the abolition of provincial government and George Grey's 1877-79 ministry. New Zealand's Parliament attracted talented men during Queen Victoria's reign, and service at both provincial and colonial levels of government was obligatory for a small clique of the colony's earliest European settlers. According to historian Edmund Bohan, "Those men who sat in Parliament between 1854 and the 1870s included some of the best-educated, most accomplished, widely travelled, colourful and interesting personalities who have ever involved themselves in this country's public life". In the bear pit that was the General Assembly, powerful personalities dominated and opportunities abounded for intrigue and power-broking.

Macandrew thrived in this environment. He was intimately associated with some of New Zealand's most original thinkers and unconventional politicians, including the Wakefield family in the 1840s and 1850s, Julius Vogel in the 1860s and George Grey in the 1870s. He was a member of Otago Provincial Council for 10 years and superintendent of Otago Province for a decade. He served concurrently in the House of Representatives for 29 years, both as a backbencher and as a minister in Grey's Cabinet; he was leader of his parliamentary faction, and in 1879 the premiership eluded him by just four votes. At the time of his death he was Father of the House. Macandrew served in most of the positions available on Otago Provincial Council as well as sitting in the first nine New Zealand Parliaments. In all, he was a constant advocate for the interests of Otago.

Macandrew's guiding beliefs were simple. He identified closely with the precepts of the Free Church of Scotland and the aims of the Otago settlement: his drivers were "education and religion, agriculture and commerce". These beliefs evolved into his political creed, encapsulated at his death in four words: "roads, population, bridges, capital". When he arrived in Dunedin, a community founded on self-sufficiency, his economic philosophy was typically Victorian laissez-faire, but he soon realised that a larger population would stimulate faster growth in this undeveloped country. In the absence of private investors with capital to build the province's infrastructure, Macandrew modified his views on self-reliance and advocated instead for the use of state resources to build roads, railways, harbours and more. As New Zealand's economy faltered in the 1870s he recognised the need for state assistance for individuals, and became a proponent of deferred payment for land and state loans to settlers. In Parliament he sought access to land for all settlers and liberal social legislation, the latter enacted a decade later by the Seddon government; and it was Macandrew who suggested unemployed colonists be given free land to enable them to be self-supporting.

Macandrew's role in New Zealand politics has been neither widely nor impartially discussed, and few historians have acknowledged his contribution to social conditions in the colony. Instead, Macandrew is largely remembered for his audacious behaviour, and is most commonly recalled as the politician who was imprisoned in Dunedin for personal debt during his first, brief term as superintendent of Otago. Using the authority of that position he declared his private residence a prison and continued to conduct the province's business from home, until dismissed by Governor Thomas Gore Browne and returned to the public jail. Even there his chutzpah was unbounded: in the ensuing election to choose his successor he mounted a campaign from prison and came a respectable second.

Ironically, given his concern with public expenditure, a considerable amount of the colony's time and resources were spent on preventing any repetition of his behaviour. By 1867, when he began his second term as superintendent, he had precipitated three Otago Provincial Council select committees, two inquiries by the country's auditor-general, an entry in the Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR) and six Acts of Parliament. As a minister he precipitated a further two select committees, and in 1880 two royal commissions investigated his ministerial performance.

His business practices provoked a similar degree of censure. The first years of European settlement in New Zealand saw explosive settlement and unrestrained expansion as a stream of colonists was matched with apparently unlimited land, and internal and external markets were ripe for development. Macandrew was one of a small group of settlers shrewd enough to grasp the opportunities to exploit the seemingly endless resources in this untapped country. A sharp-witted businessman could skim a commission from almost every human transaction in his locality, and indeed, in his first decade in Otago Macandrew accumulated assets that today would make him a multimillionaire.

The Southland Times, critical of Macandrew for much of his career, at his death in 1887 noted: "There are some politicians who are always in office and others who are always in power, which is quite a different thing. Mr Macandrew belonged essentially to the latter class. He was in office for many years, but he was in power from the time he landed in Otago ..." That Macandrew appealed to the Otago voters and was an outstandingly successful politician is indisputable. Of the 19 positions he ran for in his lifetime, he won three elections to the Otago Provincial Council and four of the five elections he contested for superintendent and lost only one of his 11 assembly races. In Otago his followers alternately abused and praised him, but when the provinces ended, his career was depicted in largely respectful terms: "The time has not yet come to write the history of this remarkable man, but the materials for a most striking biography are most abundant, and the variety of light and shade scattered through an eventful life in Scotland, England and New Zealand will be read with interest some day ... While there is much in it to warn, there is much to imitate."

The first tier of colonial 19th-century politicians is well represented in New Zealand biography. Ten of the 17 premiers - FitzGerald, Stafford, Weld, Vogel, Atkinson, Grey, Hall, Stout, Ballance and Seddon - have their biographers, but less interest has been shown in the contributions made by provincial leaders. Of the 44 superintendents, only FitzGerald, Stafford, Grey, Campbell, McLean, Rolleston and Cargill have had their lives publicly examined. This biography provides a view of New Zealand from the second tier, the provincial periphery, and places Macandrew as a skilful businessman and politician, able to advance the interests of his constituents while serving the demands of the country during a period of rapid change.

Macandrew polarised onlookers, engendered both intense loyalty and enmity in his fellow citizens, and played an important role in the making of Dunedin, Otago and New Zealand. He was active in most of New Zealand's political institutions during almost four decades of public life and mixed with the country's movers and shakers. His many-faceted life in Dunedin - his involvement in a range of commercial activities, his imprisonment as a defaulting debtor and his lengthy public service - as well as his extended parliamentary service, his brief ministerial career and his presence at many important events in New Zealand's history, make him a subject worthy of his own biography ...

Accounts of Macandrew were shaped by the social rank, economic standing and political views of the observer. He clashed with social superiors such as Governor Grey and Henry Valpy, he vied with equals like William Cutten and Johnny Jones, and while he was seen as silvery, cunning and not over-scrupulous by one contemporary, he was also considered an esteemed friend of the working class ...

Settlers looked to Macandrew for leadership, and his knowledge of parliamentary procedure made him a valuable, if contrarian, member in the fledgling provincial council where, over the years, he occupied most of the leadership positions as member, executive councillor, treasurer, Speaker and superintendent. Macandrew took advantage of his positions, however, sometimes using them as a means of salvaging his personal financial position. He used his own assets, his wife's inheritance, money held in trust for other colonists and public money to rescue his unviable business ventures. But political activism and impatience with detailed planning and accounting led to the collapse of his business world, which he never attempted to rejuvenate. His political life was characterised by his obsession with promoting major projects and a similar disregard for details, and despite his persuasiveness he was often unable to garner support for his goals: the provinces were abolished despite his desperate opposition, and his tenure as a minister ended in disarray. Ultimately, he trusted too much, borrowed too casually and was a diffident manager of men.

His career earned him few accolades. While many other ministers of the Crown were knighted, Macandrew was not. And because Grey's ministry did not survive for a full term, he did not earn the right to retain the title "Honourable" for his two years of Cabinet service, whereas his Otago colleagues did: Vogel in 1871, Reynolds in 1876, Oliver and Dick in 1884, Larnach and Stout in 1887, and Pyke in 1893.

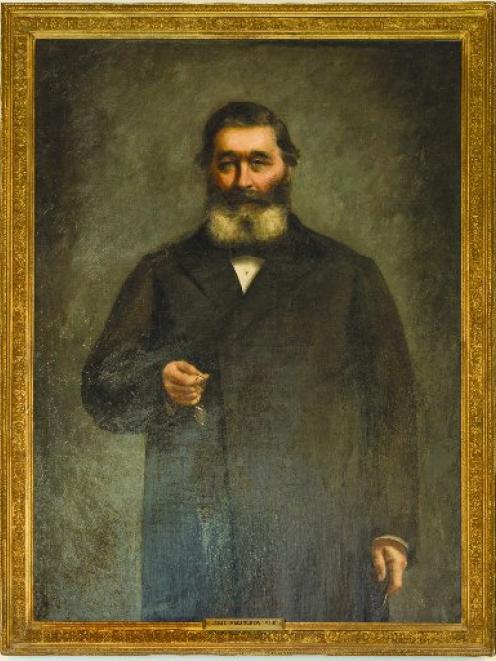

Today his monuments are few and far-flung and most are insignificant. His bust stands in front of Dunedin's Toitu Otago Settlers Museum, a full-length portrait commissioned in 1885 hangs in the University of Otago's clocktower building, and there is an eponymous bay on Otago Peninsula where he lived for much of his life. Macandrew Wharf still serves Oamaru, and a number of streets bear his name: Macandrew Rd can be found in both South Dunedin and Careys Bay, and Otautau, Milton and Owaka in the South Island and Woodville in the north all have a Macandrew St. Less obvious reminders of his enterprise are the sites of Jamestown on the shores of Lake McKerrow in Westland, Cromarty in Preservation Inlet in Fiordland and Macandrew Township near the present Riversdale in Southland. Macandrew Intermediate School in Dunedin was renamed in 2015, and all traces of Macandrew Bridge over the Kawarau River at Bannockburn, erected in 1878 and rebuilt in 1897, were lost when Lake Dunstan was filled in 1992.

James Macandrew was "a leader staunch and true" who enthused people with his vision and plans, and relied on stirring speeches to carry his audiences with him. He was sufficiently audacious to lead the development of a new and richly endowed province, emotionally resilient and ready to engage any man as an equal. Had he become premier of New Zealand with the assistance of a responsible treasurer, who knows what visions might have eventuated.

The book

Slippery Jim or Patriotic Statesman: James Macandrew of Otago, by R.J. Bunce, Otago University Press, RRP $45, will be launched on Tuesday.