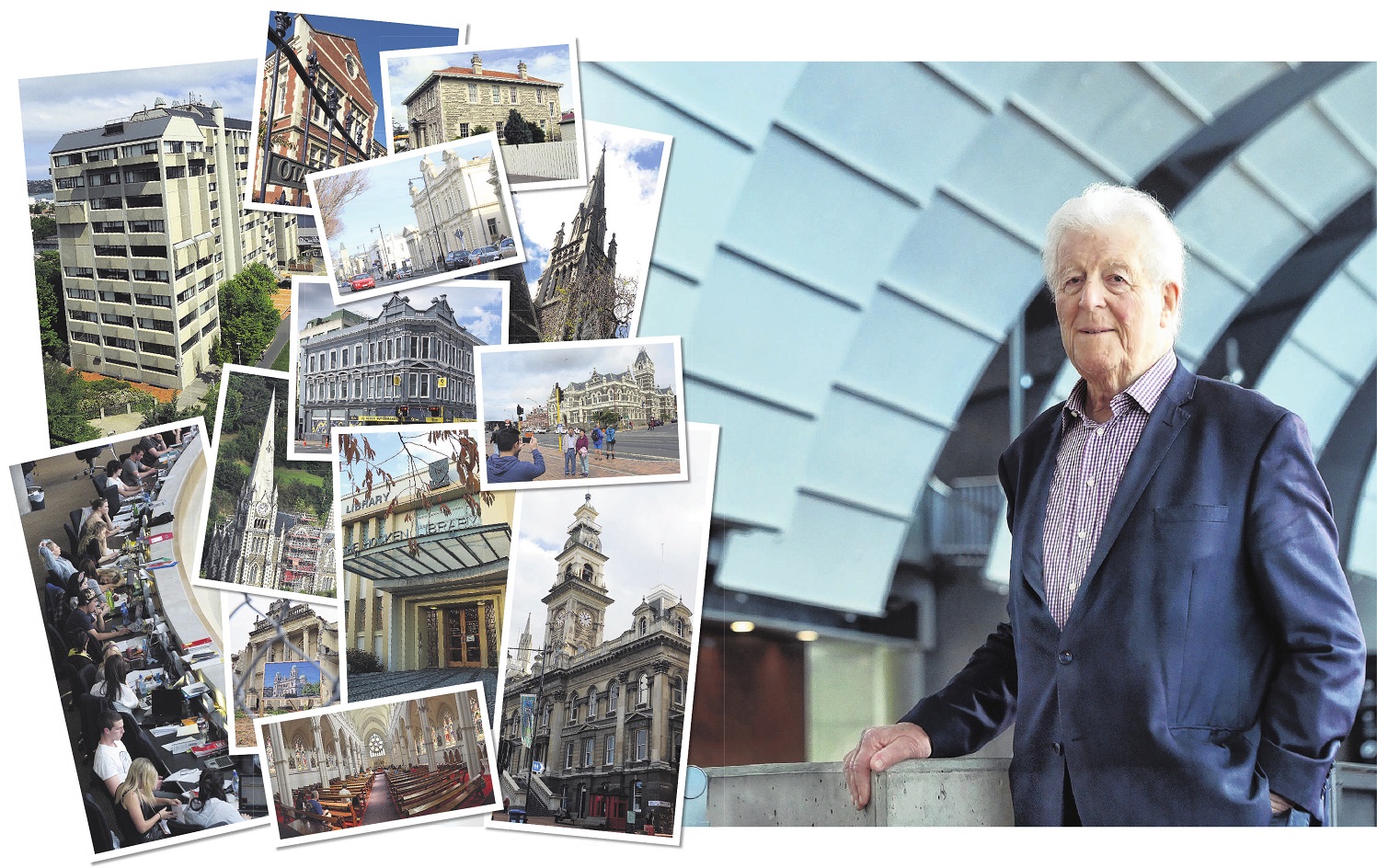

Much of Dunedin is still standing, thanks to Lou Robinson.

It is never easy to summarise a more than 60-year career. But where else would you start for a long-time structural engineer with a string of achievements, awards and endorsements?

The best special effects are the ones you don’t notice. It’s much the same for Robinson — you can’t see a lot of what he has done for Dunedin and other cities around the country, but you would certainly notice if he hadn’t done it.

His influence in protecting the city’s priceless architectural heritage is beyond question. His work to protect Dunedin’s stunning, and not always so stunning, old buildings has won him much respect and many plaudits.

Without the efforts of Robinson and others, ambling around central Dunedin to take in the heritage sights of the Octagon and the historic education triangle up towards City Rise would be a far less interesting and pleasant prospect.

"If it wasn’t for the work of Lou Robinson, Dunedin would certainly look very different and be the poorer for it," Dunedin engineer and heritage developer Stephen Macknight says.

Robinson, director of Hadley and Robinson Ltd, turned 80 in June and is not well.

"You might just say I have a condition which is incurable but treatable with the rather aggressive regime I am currently undergoing," he says.

Treatment sessions at Dunedin Hospital have been lengthy and arduous. But that hasn’t quelled the fire in his belly that burns for strong and safe buildings, and for retaining as much heritage in Dunedin as possible.

When The Weekend Mix caught up with him, Robinson was firing on all cylinders about earthquake-strengthening codes, about unnecessary heritage demolition and the poor decisions made after the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake.

After 63 years in the business, who could doubt his authority?

Robinson was born in Invercargill and completed his school certificate and university entrance exams while at Marist Brothers Juniorate in Tuakau, in the North Island.

His mother’s family were "strong Irish Catholic". He says he just about talked himself into being a brother after being taught by them and admiring them.

"You have aunts come along and they’d say, ‘what are you going to be when you grow up?’ And because you’ve been taught by the Marist brothers and you quite admire them, you just say, ‘I’m going to be a Marist brother’.

"But there’s a big difference between the way you think when you’re 15 and the way you think when you’re 17. And by the time I was 17, I knew that it wasn’t for me."

Instead, his mother said he wasn’t going to waste having gained his university entrance exams, and he started work as a drafting cadet for the railways.

"That was the only job advertised in the Southland Times at the time that required UE. So that’s how I got into engineering."

After about three years there, a year-long stint with companies involved with the Manapouri Power Station project brought him into contact with overseas engineers and their varied expertise and experience. He then went to work at Duffill Watts and King in Dunedin and Invercargill.

In 1965 he gained his New Zealand Certificate of Engineering with distinction. With that and a couple of awards under his belt, he was eligible to go straight into the third year of four in the University of Canterbury’s engineering school. He graduated with a Bachelor of Engineering (Civil) with first-class honours in 1967.

While at Canterbury University he studied with pioneering New Zealand earthquake engineers Profs Bob Park, Tom Paulay and Nigel Priestley.

"Seismic work has always been part of New Zealand engineering since the Napier earthquake. I was interested in it, and they tried to get me to stay on, Tom Paulay in particular, but I wanted to be a practicing engineer.

"I’d met Jim Hadley during my period at Duffill Watts and King in Dunedin, and he was at that stage head of department at Otago Polytechnic and about to set up his private practice. He gave me a call and asked if I would be interested in joining. So, I sort of fell on my feet.

"We established Hadley and Robinson in 1968. I was unregistered then, I hadn’t done the usual four or five years, so Jim took quite a chance really."

There was no gentle introduction for the young structural engineer when it came to working on buildings.

"I did some of the foundations for the Reserve Bank on The Terrace in Wellington. That was straight in at the deep end. And in Dunedin I did the bottling plant for Speight’s in Rattray St.

"By 1974 we’d progressed to some fairly substantial buildings for the University of Otago — finishing the design of the Richardson Building as it is known now, but used to be the Hocken Building, before the Hocken transferred to the old dairy factory in Anzac Ave, which we also did the modifications for."

The most difficult heritage buildings to assess for safety and seismic strength have always been the churches, he says.

"I’ve done seismic assessments of several churches, including Knox Church here and St Joseph’s Cathedral, and First Church in Invercargill.

"They are particularly challenging. Those sorts of structures have usually got very tall interior spaces and usually have a steeple, which people always say will topple but won’t necessarily, as some of the earthquakes in Italy have demonstrated."

But what about the collapse of the steeple and the destruction of the Anglican Christ Church Cathedral in the 2011 Christchurch earthquake?

On the finance committee of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Dunedin, Robinson chooses his words carefully.

"I don’t mourn the loss of it. But they’re going to rebuild it. But I do mourn the loss of the Basilica (Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament). It was the most important building of its kind in the southern hemisphere.

"Its assessment was incomplete in terms of remediation, given its prime importance in heritage and ecclesiastical terms. The Catholic Diocese of Canterbury made the wrong decision to demolish it, and I’ll be interested to see what they rebuild in its place."

Hadley & Robinson also completed the assessment of St Patrick’s Basilica in Oamaru.

"It’s beautiful inside, because it’s got that honey-coloured patina on the Oamaru stone. It gives the stonework and the building a beautiful soft glow."

Robinson worked on seismic assessments of Oamaru’s Victorian whitestone precinct and won David G Cox Memorial Awards for the refurbishment of the Oamaru Police Station and the Oamaru Opera House.

"The precinct is in line for becoming a World Heritage Precinct. Everyone is pretty happy with that, including the Waitaki District Council who own most of it, but it seems to be very slow."

Robinson’s honours stash includes several more David G Cox Memorial Awards — including for the refurbishment, strengthening and extensions to the Dunedin Law Courts, to Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, and Iona Church in Port Chalmers.

Late in 2019 he received the Southern Heritage Trust’s Bluestone Award for outstanding contribution to heritage conservation projects and to heritage in the city and surrounds.

Trust chairwoman Jo Galer says Robinson’s skills and knowledge have been invaluable to Dunedin.

"What we deeply appreciate about Lou — and what other engineers could learn from — is his ‘can do’ attitude to saving buildings that others may see as worthy only of demolition.

"He takes a practical yet safe approach to strengthening buildings. Where others less qualified see dire structural problems, he sees what can be done to save it. Quite frankly, we need many more of him and his skills in Dunedin.

"It is testament to him that he has used his skills for such great good — and ultimately also for the economic benefit of Dunedin. Without our built heritage, Dunedin would be a lot less remarkable, liveable and aesthetic as a place to live and visit."

Macknight agrees, saying Robinson has led by example and, without a doubt, "done more than anyone else in the city and perhaps the country" towards preserving heritage buildings.

"In the late ’80s when buildings where being pulled down around the country, Lou was able to show developers that buildings such as the Westpac Building, on the corner of George and Frederick St, could be redeveloped in a financially viable way.

"With the growing number of successful redevelopment projects at the time, developers and institutions, such as the Dunedin City Council and the university, looked at ways they could redevelop existing buildings, rather than demolish and build new. With efficient structural analysis and design, Lou was behind many of these successful projects."

Robinson’s professional work on national guidelines for the analysis and strengthening of unreinforced masonry buildings has provided engineers with the tools to understand and advise clients about what can and should be done to earthquake strengthen such buildings, Macknight says.

Robinson explains that seismic assessments on a building measure how well it performs under stress, in terms of a percentage of the New Building Standard (NBS).

"The simplest way of doing that is to see how far you can push it with the simulated forces of an earthquake, until you can’t push it any further. Let’s say you’ve got 60% of the way through — that score is 60% NBS."

These days those tests are mainly done by computer, but in the past were done by hand, using penetrometers measuring resistance to pushing and Schmidt hammers, which register the rebound of a plunger fired against masonry.

The new earthquake-prone methodology came out in 2017.

"Before that, territorial local authorities could make their own rules within certain guidelines but nothing really happened, no notices were served or anything like that. Now they’ve got an obligation to complete that review of buildings within five years.

"Sometimes they identify a building wrongly under the so-called profiles that allow them to identify potentially earthquake-prone buildings without actually doing any assessment. They might say it’s an unreinforced masonry building when it is reinforced. But by and large they’re doing a reasonable job."

The 33% score for an earthquake-prone building is a fairly low threshold, Robinson says.

"If you can’t make the 33%, usually the remedy to get above it is quite straightforward. That threshold has been set by boffins, but more particularly by Parliament."

Should we be worried about earthquake-prone buildings in Dunedin?

"I’m not too concerned. If an earthquake came along that just tested the earthquake-prone threshold, most of Dunedin would be OK.

"My big concern would be, if we got an earthquake like they got around Christchurch, that the government would not have the will to rebuild. They were spending half a billion dollars a week at one stage in Christchurch, but I don’t think they would have that sort of resolution here. So, I think we’d lose a lot of Dunedin."

After the Canterbury earthquakes, Robinson had a card that allowed him to access and study damaged buildings.

"They say we learned a lot from the Christchurch earthquake, and had to change our codes and everything else. But there was nothing that earthquake showed us that we didn’t already know. What we had done in New Zealand was choose to ignore that.

"Take liquefaction. We knew it occurred, but you didn’t have to design for it, though the designs for the methodologies were already available in the ’80s. But it was too hard, too much demand on the poor old practitioner.

"On the other side of the coin in Christchurch was the wholesale demolition of buildings that didn’t need to be demolished. And government departments shifting from buildings that several people said were perfectly all right, like the law courts.

"But they wanted a new law precinct. And they wanted a new convention centre."

One project stands head and shoulders above the rest for Robinson. He says the University of Otago’s Information Services Building was not only hugely challenging but highly enjoyable to work on.

"What made this project particularly memorable and enjoyable was the expressed wish of the principal architects — Hardy Holtzman Pfeiffer from the United States — for collegiality. They listened carefully to all suggestions made to solve each problem.

"They wanted stairs that went up the whole three storeys with no vertical support, no props underneath. So we designed the hanging stairway, just supported off the floors.

"There’s a wall of curves in plan through the whole length of that building and it’s faced with Oamaru stone, with a concrete core. That becomes one of the main shear walls for the building, but because it’s curved in plan that makes it quite challenging to solve the rest of the structure. The interior frames had their own difficulties too.

"It’s one of the very few in Dunedin that reflect high international standards of design and amenity. The large volumes in the concourse spaces elicit feelings of light and airiness, and parts of the former library have been seamlessly integrated into the new building.

"When you walk through that building, you say: ‘This is magnificent. This is an educational space. I could learn here’."

In the 1980s, former New Zealand Historic Places Trust Otago-Southland regional officer and Dunedin heritage doyenne Lois Galer and Robinson became a formidable team beating back the bulldozers of so-called progress as they impatiently revved their engines across the city.

"In those times, Dunedin’s historic buildings for the large part went unappreciated and deemed fit only for demolition," Galer says. "Trying to save them from demolition seemed nigh-on impossible. The Otago Girls’ High School and the Municipal Chambers were the latest deemed for the chop as ‘earthquake risks’, but besides that the DCC had this weird idea Dunedin needed to rid itself of its Victorian image, if it was to compete with other New Zealand cities.

"My job was to convince the city fathers that getting rid of Dunedin’s built heritage was shooting the city in the foot; that the tourism potential of the city would be destroyed as a result."

Enter Robinson, whose plan to quake-strengthen OGHS was cheaper and as effective as the Ministry of Works’ suggestion, but turned down in favour of a new building. Robinson and the Historic Places Trust won the ensuing battle with the school’s board of governors to save and restore the building.

The city council’s vote to demolish the Municipal Chambers was also repulsed by Robinson and city architect Robert Tongue. Not only was it retained and totally restored, but also the clock tower was rebuilt in its original form, she says.

"From then on, Robinson was the man to call when demolition was proposed."

Robinson’s legacy was secured.