Fifty years ago, on October 8, 1968, the MacLeod family, of Brockville, arrived at Dunedin's Rattray St Wharf, a momentous homecoming by sea. Renowned globetrotters, the family of eight - parents Alan and Joan and their six children - had made two overland journeys to Scotland through Asia and Europe in a remodelled army vehicle in 1963 and 1968, travelling a total of 93,000km.

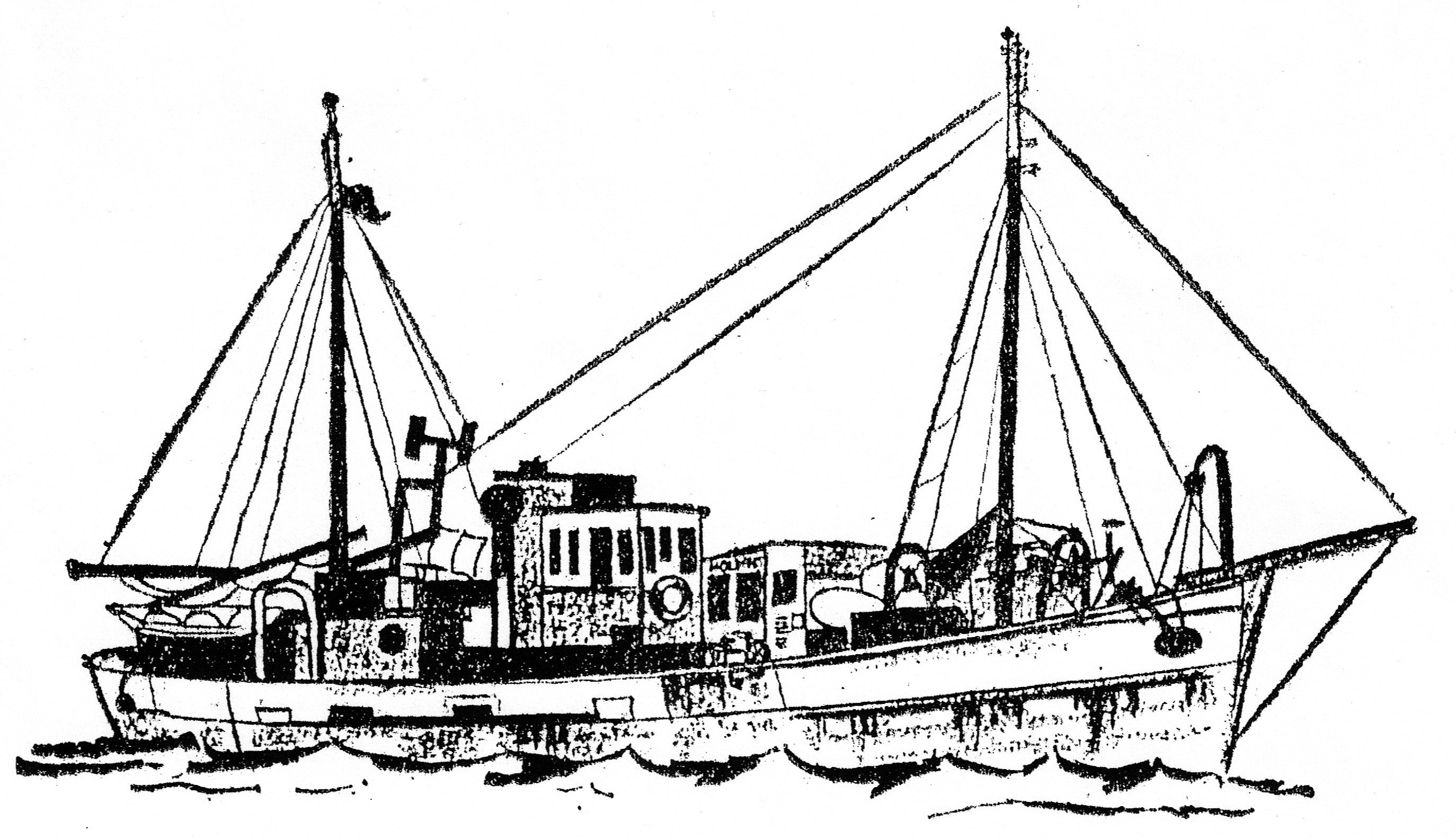

Their kind of overland family travel was novel, a combination of adventure and pilgrimage. Now they were returning from their second remarkable trip aboard a wooden minesweeper-cum-trawler called Heather George, much to the delight and wonder of crowds of well-wishers at the Steamer Basin that day.

It was the end of a 26,000km voyage via the Panama Canal, from Milford Haven in Wales to the vessel's new home port on the other side of the world, by way of the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

I was on the wharf that day, a young reporter from The Evening Star, and like most of the onlookers I was goggled-eyed as the 30m-long MacLeod vessel came alongside the wharf, its deck loaded up with all manner of gear, including their faithful "caravan". I thought there and then the family's experiences abroad might make an inspiring travel book.

To have travelled overland all the way from their pig farm on the outskirts of Dunedin City certainly impressed the Clan Chief.

"Imagine my amazement and delight," wrote Dame Flora, "when all eight MacLeods marched into Dunvegan Castle one afternoon, spick and span, neat and clean after many months of living and sleeping, cooking and eating, washing and mending, reading and writing in their tiny home on wheels".

The voyage home from that second trip took more than six months. Heather George weathered storms, difficult ports and dangerous situations, including a "man overboard" drama in the North Atlantic Ocean and the salvage of a vessel from a reef in French Polynesia at great risk to their own.

A couple of months after arriving in Dunedin, the family's sturdy oak vessel sailed off to Stewart Island for a week's exploration of the island's east coast - my first time at sea - and soon after that she was fitted out for commercial fishing. She ended her days, after the MacLeods sold her, wrecked on the Kapiti coast.

Here is a chapter from my story about the adventurous MacLeods, as the Heather George made her way across the North Atlantic Ocean.

A lurch, a plunge ... a pale face in a torch beam

May 5, 1968, was not extraordinary from a weather point of view. The sea was up slightly with the wind from a southerly quarter. As evening neared, Alan MacLeod began sawing firewood for the galley's stove. Joan MacLeod, near the stern and obscured from her husband, was splitting the sawn pieces of firewood with an axe.

In the periphery of her vision she glimpsed a movement near the stern. Perhaps a fish basket was disturbed. But the splash that followed the movement caused her to wonder what had fallen overboard - a piece of equipment perhaps?

She looked up. To her extreme horror she saw a white face bobbing in Heather George's wake. It was disappearing into the darkness at an astonishing rate.

Joan screamed ...

In the warm post-dusk of May 5, young Alan, also known as Ginger, the older of the two boys at 16, had been whiling away time in the lifeboat. About 8 o'clock he decided to report back. During the day Malcolm and he might stay secluded for hours but at night Ginger fancied his parents might feel more concerned about his absence.

He worked his way towards the deck by way of the stern. Usually there was a boom that you could hold on to for the long step to the gunwale; on this occasion it was out of position. So he jumped - and faltered as the ship gave a lurch. For a desperate few seconds he was neither securely aboard nor in the water. His feet were on a beam, his shins were pressed against the gunwale but the upper half of his body leaned out over the choppy Atlantic. He overbalanced, grazing his shins in the plunge to the sea.

By the time he surfaced Heather George was racing away. She was making 7½ knots (14 kmh) but to him it seemed a lot faster. He shouted for help - loudly but not in a panic. As he began kicking off his gym shoes, Ginger saw his mother look up and heard her muffled, agitated cries. Alan senior had not heard the splash or even seen Ginger fall - he and daughter Flora, who was helping him, were the only other crew who could have spotted the mishap.

Then came the scream.

"Ginger's overboard! Ginger's overboard!"

Alan, who reacted the instant he saw his wife's horrified look, had the starboard side covered. His first action was to throw overboard a lifebelt lying loosely near the lifeboat. Next, he ran forward to sound the ship's bell.

Crewman Roger Dowman, at the wheel, began to bring Heather George around on to her back bearing, which they had practised for a man-overboard incident.

The moonlight was a godsend but it cast deceptively streaky shadows across the swells. They needed a torch if Ginger were to have any chance of being rescued. He remembered the torch down below, having put new batteries in it the previous day.

Meanwhile, Flora had moved around to the port side, near where her brother had fallen. She threw a heavy log - fished from Casablanca Harbour for firewood - into the water. She stood by her mother, gazing intently at the black sea and fearing the worst.

By now all crew members were involved in the rescue.

Alan noticed the wind had picked up as the vessel had come about. In fact, it was generating a few white horses, making the task of finding Ginger much more difficult.

Ginger, meanwhile, found the water surprisingly tepid. With his shoes off he had no difficulty in staying afloat, though the waves often broke over his head, blurring his view of Heather George's navigation lights. Otherwise he felt quite comfortable. Never for a moment did he consider the possibility of not being rescued, of being listed missing at sea, presumed drowned.

But he did wonder why the hell the ship was taking so long to get back to him. Occasionally he would yell in the ship's direction: "Hey! Over here!" As Heather George edged closer, he called louder ...

Older sister Cairine, standing alone on the superstructure behind the wheelhouse, was almost resigned to the horrible prospect of never seeing Ginger again. Then she heard a cry from the sea, somewhere to port, at about the same time as her father, up forward, fixed Ginger's pale face in the extremity of his torch beam. The lad was 60 to 80 yards off, barely visible.

"Take it easy!" Alan roared. "Keep yourself afloat! We'll ease over to you!"

"It's all right, Dad," came the reply. "The water's quite warm!"

Ginger's nonchalance was hard to believe. His father's stomach was in a knot. He felt he had never moved so fast in all his life as he had that night. In the engine room, cut off from the developments topside, engineer Geoff Leeden was worried. The supply of compressed air - used to kick the Crossley into life - was dwindling as a result of a number of orders to restart the engine. He knew the generator would restore the supply but that would take time - precious searching time. His concern was unfounded, however, as Ginger was well on the way to being rescued.

Alan MacLeod looked to be ready to dive overboard to help recover his son more quickly but Ginger told him that was unnecessary and to prove it swam the last few yards to catch the rope brother Malcolm had lowered from the boom.

He clung there for a minute or two and had such a firm grip on the rope that when Heather George heaved in a swell he did too. On every downward swing a ducking awaited him. Ginger felt it was time to get aboard and half paddled, half swam to the ship's side, where he was hauled in jointly by his father and Cairine.

"Go change your clothes now," ordered his mother.

She stood there, hardly believing he was alive.

"Thank God. Thank God," she murmured. The others were silent.

A search for the two lifebelts began. In the wind they had drifted a considerable distance. One was harpooned from the water, though Ginger, having returned from the accommodation with a new set of clothing, suggested he swim to retrieve the belts.

"You're on board and you're bloody well staying on board," his father said.

The Casablanca log appeared near the ship. Joan suggested it should be rescued as a good luck charm - that superstition again. Her husband thought it was wasting time to recover driftwood. The log stayed in the water. Twenty minutes after the rescue Ginger reported for his wheelhouse watch, apologising for his tardiness.

Neville Peat is a Dunedin writer. His latest book, The Invading Sea: Coastal hazards and climate change in 21st-century New Zealand, is out next month.