James Porteous, owner of Oamaru Organics, points to a whiteboard in his farm’s packing room where his wife Atsuko and their two children are loading potatoes into small paper bags.

Scrawled on the board is the answer to the question: "Where can the public buy your locally-grown, chemical-free, veges?"

It isn’t supermarkets. The farm sells at the roadside, at Dunedin’s farmers’ market, through a few independent stores and takes online orders.

Small-scale vege farmers around Dunedin trying to farm in ecologically-focused ways are few and mostly smaller than Oamaru Organics. Mr Porteous uses a tractor but others are using forks.

They share a mission to grow produce for local people in ways that support biodiversity, human health and local resilience, but are frustrated by a food supply system that they say is stacked against them.

The glaring problem is the David and Goliath difference between the small farmers and the supermarkets owned by two corporations, offering one-stop shopping and low-cost veges. Very few vegetables are labelled as grown sustainably around Dunedin.

Supermarkets dominate

"The supermarkets push chemical, pesticide veg, not organic veg," Mr Porteous says. "That is what we are up against ... they dominate."

He says supermarkets demand their cut and low prices for shoppers. The system supports large-scale farming for domestic and export markets, using chemicals to increase yield and travelling to get to market, causing emissions and crash risk.

Popular root vegetables — such as potatoes, carrots, and onions — take time to grow, but supermarkets offer multiple varieties in big bags at low cost, not labelled organic and from wide-ranging farm locations. The system fails to support Dunedin’s food resilience if the crops fail, or cannot be transported here due to extreme weather or other disasters.

In the past, fertile land around Dunedin was tilled by multiple market gardeners — in Outram, Forbury and around Oamaru — selling a variety of produce locally through small stores. Many gardeners were immigrants from China.

The gardens have nearly gone, with descendants of immigrant farmers leaving the land. The ODT found two local market gardeners using organic farming practices and supplying Dunedin supermarkets. A handful of others were supplying chefs and small stores.

The stores have nearly all gone, too. Taste Nature in Dunedin and the Waitati Merchant in Waitati are exceptions. Amee and Rafferty Parker, who took over the Waitati Merchant last November, understand their role helping the community eat local food.

"We have a holistic role. We are not just a store," Ms Parker says.

Organics Aotearoa New Zealand (OANZ) chief executive Tiffany Tompkins says she was left "shocked" and "despairing" when she arrived from the USA and found that out of 197 pesticides banned elsewhere, most were allowed here. Availability of local, organic produce needs to reach a "critical mass and have a better supply chain."

Forest & Bird’s regional conservation manager Scott Burnett summarises the challenge.

"Large-scale, industrial farming is entrenched in New Zealand’s economy and culture, with substantial financial and political backing".

He calls for subsidies or grants for small, organic farms.

"These farms create habitats for native species, promote soil health, and reduce chemical runoff into waterways."

Empty shelves

Foodstuffs (which owns the brands Pak’nSave, New World and Four Square) and its rival Woolworths (which owns the brands Countdown and FreshChoice) were both asked to provide percentages of their fresh produce sourced from local and organic producers.

Neither answered the question. They both pointed the ODT to their sustainability reports — and Foodstuffs has potatoes on the cover of its report — but neither report focused on local, organic veggie provision.

A Foodstuffs spokesperson said its store owners could source veggies from Foodstuff’s distribution centre in Christchurch "and/or arrange direct delivery from local growers".

However, its franchise manager Tim Cartwright said central Otago stone fruit went to the FreshChoice Roslyn store via a Dunedin "trading facility".

Woolworths New Zealand’s managing director Spencer Sonn said the company had invested in lower-emissions refrigeration and had an "ambition" to transition its home delivery vehicles to be electric by 2030.

Spokespeople for both food giants said organic produce sales were increasing, but Foodstuffs admitted it was happening "slowly".

This month, the ODT visited Foodstuff’s New World supermarket in North East Valley and Woolworths’ Countdown supermarket in central Dunedin. Both had small shelves designated for organic produce.

In New World, the organic shelves were half empty. One shopper was staring at it and said she tried to buy organic, but its availability and pricing was variable.

Two types of bagged organic potatoes were found on shelves opposite, surprisingly discounted but easy to miss among 41 types of bagged potatoes not labelled organic.

There were no carrots labelled organic, but many carrots for sale. One of the providers of non-organic potatoes and carrots was Pyper’s Produce, which farms hundreds of hectares in Southland for export and eating here.

The ODT asked Pyper’s Produce about its chemical use, sustainability and sales to Asia and the Middle East. The company declined to comment and referred the ODT to its trade association Horticulture New Zealand, which did not answer questions and referred the ODT back to OANZ.

In Countdown the organic shelves were even emptier. Only walnuts from Lincoln and red onions from the USA were on offer, plus organic cherries, of unclear origin, on a different shelf.

There were several large bins near the store entrance groaning with vegetables and fruit not labelled organic.

The produce was from New Zealand and abroad, including bagged potatoes from Balle Bros, branded Little Diggers. The bag of small, waxy potatoes said its source could be traced by entering a code online. It didn’t work.

Balle Bros sales manager Kathy Cowell apologised and investigated. The potatoes were from Kaitaia, Northland. Ms Cowell said this was due to timing of growing seasons, meaning the company could bring the potato variety "to market as soon as possible".

Woolworths’ Mr Sonn said the company is supporting a trial of "regenerative" farming techniques with one of its big farm suppliers. LeaderBrand Produce’s website says the purpose is "rejuvenating intensively farmed land" and initial results show "microbes and organisms are returning" due to use of compost and cover crops.

Both techniques have long been used by ecologically-focused farmers.

Cost challenge

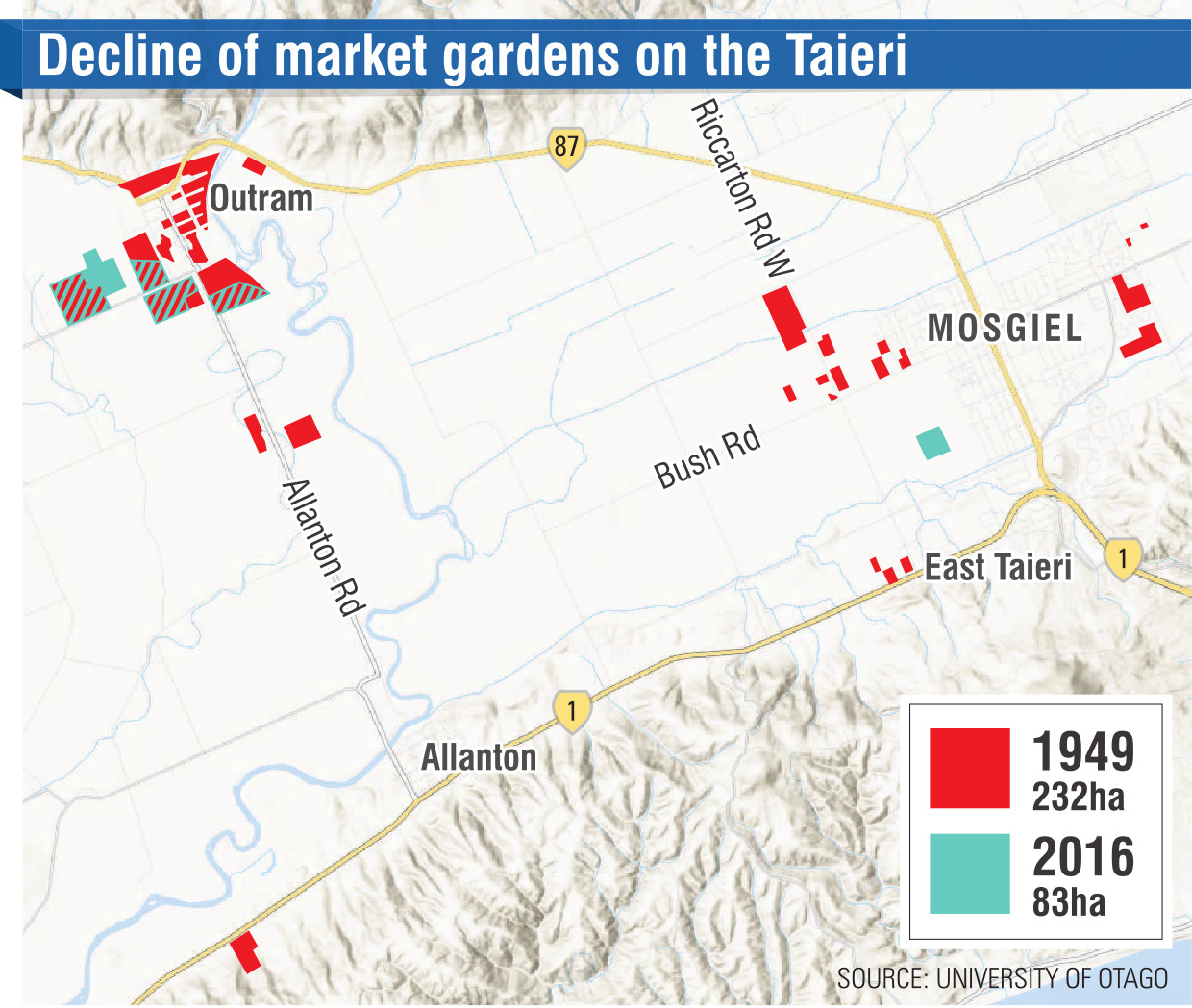

University of Otago’s Dr Sean Connelly lectures on food resilience and provided the ODT with maps showing the decline of local market gardens. Land used for market gardening on the Taieri had reduced from 232ha in 1949 to 83ha by 2016.

Dr Connelly argues that inadequate environmental regulation, for example of river standards, is a "hidden subsidy" of chemical-dependent food production. It is easier to find out what New Zealand exports than how much is grown locally for local mouths, he says, and becoming a certified organic producer can be a high bar to jump.

"In New Zealand we don’t value food. We value commodities we export ... and people can choose to act on principles or not. They can go to the farmers’ market on a Saturday or have a lie-in and go to the supermarket."

Dr Connelly also recognises that some people, such as the homeless, don’t have choices.

"We don’t acknowledge that there are people hungry here in Dunedin every day. We turn a blind eye."

He suggests that procurement policies by large institutions that provide food — such as universities, prisons and hospitals — could stipulate purchases from local, ecologically-focused farms. Councils’ encouragement of market gardening and help for community gardens is laudable, but can’t fix the problem, he says. Farming was hard and took time.

After a career as a chef, Carl Barnes, 55, is prepared to try. He has spent two years seeking two acres (0.8ha) of flat, arable land in Outram hoping to farm organically.

"Coming from a hospitality background, I understand good food, and communities looking after themselves is the way forward."

Others have managed it.

Small shoots

Jed Tweedie and Skye Macfarlane have been farming since 2016 on their certified-organic land at Purakaunui. It is 11ha, but they grow micro-greens on less than half a hectare. Twice as much space is fenced off for nature and the rest is low-density grazing.

Their micro-greens are available in Dunedin’s New World stores and Roslyn’s Fresh Choice under their brand Vern Paddock Project.

Mr Tweedie says he is welcomed by the supermarkets and hopes to sell more there, but supermarkets seemed not to be "proactive" about approaching organic farmers. He comments on the root-vegetable challenge.

"It’s difficult. We can grow carrots and sell them direct to our cafe customers, but they are prepared to pay more."

He might sell baby carrots at $17 a kilo. Online, New World was selling large carrots this month at $3.29 a kilo.

Mr Tweedie points out that when people say organic vegetables are expensive, they are commenting on the difference between the cost of producing a vegetable in a sustainable way and the "incredibly cheap" price point put on non-organic vegetables.

"Being an organic farmer is like trying to run a 100m race with one leg tied up and maybe both arms behind your back as well. Any kind of profit means I get paid probably half minimum wage for myself plus two part-time living wage staff ... It’s a tough business with very low margins."

He mentions his rates bill.

"I have to sell a lot of organic lettuces just to cover it ... The council employ people to look at local resilience and are always asking why we aren’t scaling up or there aren’t more local growers, but don’t support us."

The Dunedin City Council says it undertakes a number of initiatives to promote commercial market gardening. There is a DCC online guide for people wanting to get started.

The organisation Village Agrarians helps small, ecologically-focused farmers, lists available land for market gardening and is interested in the concept of land trusts to ringfence land for sustainable farming. It has also commissioned a feasibility study about opportunities for scaling production and sales.

Co-ordinator Rebecca Perez says this could all help to "get land out of the hands of the mainstream commodity market and back into the community ... The supermarkets killed the local food system."

Ms Perez theorises that perhaps more of Mr Tweedie and Mr Macfarlane’s land could be farmed, perhaps using a tractor. Mr Tweedie is open to suggestions, but says there is limited water.

"Anyone else wanting to grow here would have to do a version of dry cropping." A water bore could be a possibility, but might not be sustainable.

The point is made: farming needs to be within the land’s constraints.

Magic market

Otago Farmers’ Market’s manager Michele Driscoll says she would like it to be "the norm" for everyone to shop there for veggies and more.

"The beauty of the market is that you get to talk to the farmer. It is a direct line of communication."

The market would love to see more certified organic growers at the market but "it would be good to see the cost of getting certified come down".

"It is tougher for smaller growers. Organisations like Horticulture NZ tend to be there for the big guys who are exporting ... because that is what brings in the dollars."

"If New Zealand celebrated organic growing and there was enough to feed our communities it would be amazing for our economy and create a really healthy nation. We are not even feeding our country at the moment. We are exporting most of our food and importing food back, which seems crazy. The food miles are extraordinary."

Privilege paves a way

James Porteous of Oamaru Organics says the farmers’ market and its efforts getting people to shop locally is "magical", but agrees people on the breadline "are going to Pak’nSave or the food bank".

He recognises his own privilege enabling him to farm. He is university-educated, owns a Thai restaurant — and previously owned a chain of them — and an organic soup brand.

Vern Paddock Project’s Mr Tweedie was formerly a mechanical engineer.

Next door to Mr Tweedie’s land is another market garden, run by tenant farmers Lian Redding and Fiona Collings. Mr Redding previously owned an organic breakfast cereal company and made the change because he was sick of working in a factory and Ms Collings wanted to grow.

Their idyllic, tiny, prolific plot slopes down to Purakaunui Inlet and the food they grow includes zucchini, salad leaves and tomatoes. They use hand tools, and alpacas are used as natural lawnmowers. This year, they are trying to farm without additional compost. They are growing onions, but only for their family.

Mr Redding is grateful for the lifestyle, which he says is a common dream "but not a lot of people do it."

The couple can’t afford their own land, he says. They sell under their brand Waewae Permaculture in the usual places — the farmers’ market, small stores and from their own gate — and recently started supplying Fresh Choice Roslyn, which Mr Redding says is "going well".

The couple don’t prioritise supplying the hospitality industry because "it is a small scene, hard, and kind of taken already."

One of the growers supplying chefs is Goodwood-based market gardener John McCafferty, who trades as Pleasant River Produce. He farms about half an acre and sells crops such as salad mixes and herbs to Taste Nature and chefs you can count on one hand, including the Dunedin cafe Big Lizard.

He has also planted thousands of native plants on another part of his land, with the help of a government scheme.

He helped train Ms Collings, loves what he does and also recognises his privilege at being able to farm and raise three children. He acknowledges the help provided by his partner’s income. She works full-time, elsewhere.

Mr McCafferty is certified organic but suggests the ODT uses the phrase "ecologically-focused" to describe efforts of small farmers who are avoiding chemicals, selling locally and contributing in other environmentally-friendly ways. He supports Village Agrarians’ efforts to look at scaling.

"In New Zealand we are taking off with this small, one person does it all, approach ... but there is no reason why working on a bigger scale should mean taking short cuts ... we should be looking to provide for the broader community."

A growers’ hui to discuss collective working is being organised.

Oamaru Organics’ Mr Porteous takes the ODT to visit his friend the "Dirt Doctor", who he says is "the puritan" of organic farming. The Dirt Doctor is Jim O’Gorman, founder of Taste Nature, who lives and grows veges on half a hectare in Kakanui.

Mr O’Gorman shows the ODT his technique of rotating tomato and potato crops in polytunnels with little concern about weeds. Weeds are a source of nutrients the earth needs, he says. He lops weeds back in a technique he calls "chop and drop".

Mr Porteous says chemical-fuelled vegetable farming is "planting into cardboard" due to nutrient depletion.

"There is a complex system under our feet that we ignore at our peril."

Back on his farm, he grabs a handful of his own, rich, soil and urges the ODT to sniff it.

"Smells good doesn’t it? It’s addictive. You could sell it by the jar!"