A monster quake is brewing deep within the South Island’s Alpine Fault. But, as the clock ticks down, just how ready are we? What if the shaking started now? Chris Morris reports.

The roar fills the air moments before the ground begins to heave.

It arrives without warning in Queenstown, while you are in the shower, at work, sipping a coffee or climbing into bed.

The shaking hits a second later and is the most powerful force you have ever felt — a sudden, intense turbulence, accompanied by the din of shouts, screams and crashing and cracking property.

You try to find shelter, but struggle to move as furniture lurches across rooms, contents explode from cupboards, televisions topple and windows shatter.

Buildings start to crumble as chimneys crash down and facades peel off, injuring and killing those caught below.

The violent vibrations turn the ground to liquid in places, and then entire mountain faces begin to give way.

Thousands of tonnes of rock tumble down, sweeping away anything in their path, blocking highways and trapping survivors in suddenly isolated communities.

One giant landslip crashes into Lake Wakatipu, sending a wave surging into Queenstown Bay to inundate nearby streets and shops.Another seals off the road to Milford Sound, trapping thousands more visitors in a dead-end street.

Longer, rolling shockwaves spreading across the South Island damage buildings and roads in Dunedin and are powerful enough to be felt in Sydney.

And, just as you think it can’t continue, it does — for three of the longest minutes of your life.When the shaking eventually subsides and the dust settles, you realise your ordeal has only just begun.

Now you face a whole new world of challenges — how do you find your family, in a town turned upside down, without a working cellphone? How do you cook food in a house with no power, and how long will you wait, reliant on dwindling supplies, until help arrives? Then an aftershock hits — the first of thousands.

You realise a long and difficult road to recovery lies ahead.

Unfortunately, this is not just a bad dream.

It is a scenario being planned for by the South Island’s Civil Defence authorities as they prepare for the magnitude 8-plus earthquake believed to be brewing deep inside the Alpine Fault.

It is the type of rupture that has occurred somewhere on the 600km fault, running up the spine of the South Island, on average every 300 years or so.

The last one was believed to have stuck 299 years ago, in 1717, meaning the clock is ticking, as scientists estimate there is a 30% chance of another major quake within the next 50 years.

And when — not if — it arrives, it is expected to be the biggest earthquake felt on our shores since the arrival of European settlers.

The land could move by up to 8m horizontally, and 4m vertically, as the shaking continues for up to three minutes.

But with Christchurch still rebuilding after its deadly 2011 earthquake and Kaikoura still being rattled by aftershocks following last month’s big shake, just how ready are we? Otago Civil Defence and Emergency Management Group regional manager Chris Hawker did not pull any punches when asked this week.

"Honestly, I think we’ve got a lot to do," he told ODT Insight.

"I think there is a high degree of apathy, quite frankly."

It is a view shaped partly by Mr Hawker’s experience living through the Canterbury earthquakes, before moving to Dunedin earlier this year.

Those who had lived through a major earthquake — or were close to those who had — seemed to be more proactive now in preparing for the next one, he believed.

Others without the same direct experience seemed more content to assume "it’s not going to happen to me", he said.

Events in Canterbury and Kaikoura proved people needed to be ready for the unexpected at any time, he said.

"You don’t necessarily have the time that you’re going to need.

"We’ve got to be prepared for the fact that it could be 4.30pm tomorrow afternoon."

And, as Civil Defence staff and scientists absorbed fresh lessons from Kaikoura, one was already clear.

Anyone preparing for the Alpine Fault earthquake should expect to have to survive without help for a week or more, he said.

When Kaikoura’s earthquake struck at 12.02am on November 14, the town of about 2000 permanent residents and roughly 1000 visiting tourists quickly found itself cut off by road.

And, with a fleet of helicopters and naval ships providing the only way in or out, it still took three days to evacuate tourists and ease the pressure on residents’ dwindling supplies.

autoplay:0]In an Alpine Fault earthquake, the damage would be more widespread and the wait for help much longer, Mr Hawker predicted.

An international relief operation would be required as stretched local Civil Defence authorities focused on those at greatest peril, he said.

Others who were isolated, but in less immediate danger, would have to fend for themselves and not wait for the "Civil Defence cavalry" to arrive, he said.

"The chances of actually being able — in a major event — to get the things that are needed in to you within three days is very unlikely.

"Don’t rush out your door and start looking for the first helicopter, because it’s unlikely you’re going to see it for some time, unless it’s flying over, heading for someone else."

It was a scenario reinforced by Prof Tim Davies, of the University of Canterbury, a specialist in natural hazards and disaster management.

Prof Davies, who stressed the need to prepare for the Alpine Fault earthquake in a 2007 speaking tour, said this week authorities could face a series of unique challenges.

That included thousands of tourists stranded by landslips in places like Queenstown and Milford Sound, who might need evacuation, or others stuck high up on the region’s skifields.

Mountain access roads could be impassable and base buildings could also be damaged by the shaking or a torrent of water released if a skifield reservoir failed, he said.

And, as well as the tsunami threat to Queenstown or Milford Sound, landslips that created temporary dams in rivers could also send a torrent of water downstream when they failed. A slow-moving tsunami of sediment could also wash down rivers later, diverting some rivers from their natural paths and affecting roads and nearby communities, he said.

If sediment built up on the Shotover delta, where it met the Kawarau River, the outflow from Lake Wakatipu could be restricted, increasing the flooding risk in Queenstown.

"That’s just one example ... there’s quite a lot of stuff to think about."

And, while Queenstown was "closest to the barrel of the gun", an Alpine Fault earthquake would cause widespread damage across much of the South Island, particularly in Westland.

"When the Alpine Fault goes, the West Coast is going to have problems, there’s no doubt about that. We’ve done a few scenarios for the West Coast and they don’t look particularly pretty."

The death toll would depend on the quake’s timing and location, but could vary from dozens to 1000 or more, he believed.

While Dunedin would probably escape the worst of the damage, it faced other problems, particularly if the South Island’s remaining road transport links were cut, he said.

At present, following the Kaikoura earthquake, the lower South Island’s road link to Picton — and then via ferry to the North Island — relied on a single tenuous stretch of State Highway 6 between Murchison and Kawatiri, he said.

"We’re totally reliant on one single stretch of highway ... if that goes out, we’re totally stuffed," he said.

Losing the link would leave the lower South Island reliant on coastal shipping, but the region’s ports were also a "potential crisis point", he said.

"If Port Chalmers is out of action, for instance, you’ve got a real problem.

"It pays to stand back a long way and look at these things with a very broad focus, I think."

Port Otago chief executive Geoff Plunkett said the threat of a major earthquake was "one of our most significant risks", but one he was confident the port could withstand.

Parts of Port Chalmers were built on reclaimed land that was vulnerable to liquefaction, which could reduce the port’s operating capacity, he said.

A powerful quake could also damage the sea wall holding back the port’s reclamation, as happened in Wellington, partially collapse the Otago Harbour shipping channel, or cause a landslip that blocked State Highway 88, he said.

However, such a powerful earthquake was also likely to cause widespread damage elsewhere, restricting access to the port anyway, he said.

And while the port’s capacity could be reduced, so too would demand for it from Otago exporters, freeing up capacity for incoming emergency relief supplies, he said.

Mr Hawker said it was the kind of scenario being considered as part of a joint planning project, dubbed AF8, named after an Alpine Fault magnitude-8 earthquake.

Civil Defence staff from across the South Island were combining with experts from the universities of Otago, Canterbury and Victoria, and GNS Science staff, in the project.

The aim was to consider, and plan for, the likely impact of, and response to, a major Alpine Fault earthquake, including how international help would "plug in" to local relief efforts.

"The last thing in the world we want is to have a bunch of people arrive to give us a hand, and find that we are in complete and utter disarray."

But, while co-ordinated planning was under way, big questions remained, he said.

Some, like how to supply or evacuate 90,000 cut-off residents in the Queenstown Lakes district, were already being considered.

But other questions, like the risk of a tsunami on Lake Wakatipu, or how long Queenstown’s hotels and skifields could care for stranded guests, were yet to be answered, he said.

"From our perspective, this is something that organisations and institutions need to be thinking of themselves.

"I think we’ve got a lot of things we need to focus on."

And, as the work continued, Mr Hawker had some simple advice for people wanting to get ready.

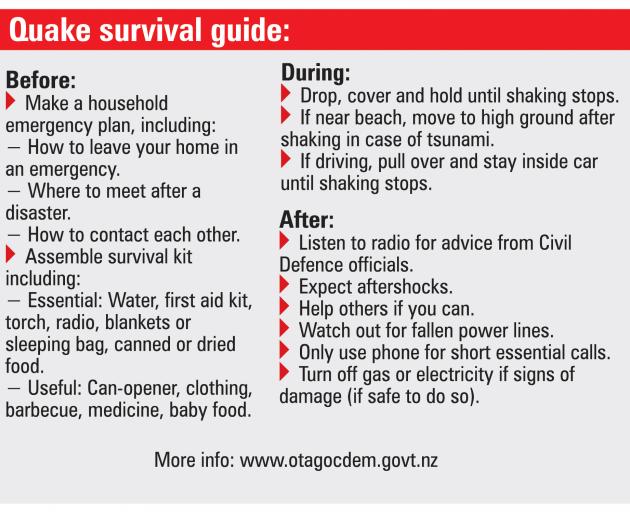

Ensure there was enough water and non-perishable food in the home to survive for a week, and plan with your family how to contact each other, and where to meet, following a major disaster.

"The first thing everybody does in a major event, before you do anything else, is that you think about the people that are dear to you.

"If you’ve done those two things, you’re well on the way."

Then it was just a matter of riding out the shaking when it came.

"It [will be] quite interesting and quite scary. I term it a very inclusive earthquake, because there’s not going to be very many people on this island that aren’t going to feel it."