Ms Vining’s late husband, Blair Vining, was responsible for New Zealand’s largest cancer petition.

Now, Ms Vining said a dear friend had been diagnosed with lung cancer. It was curable when it was first detected.

"And due to the unnecessary delays, she’s just been told she’s incurable," Ms Vining said.

"That just breaks my heart, because Blair fought so hard to ensure that those waits didn’t happen to anyone else.

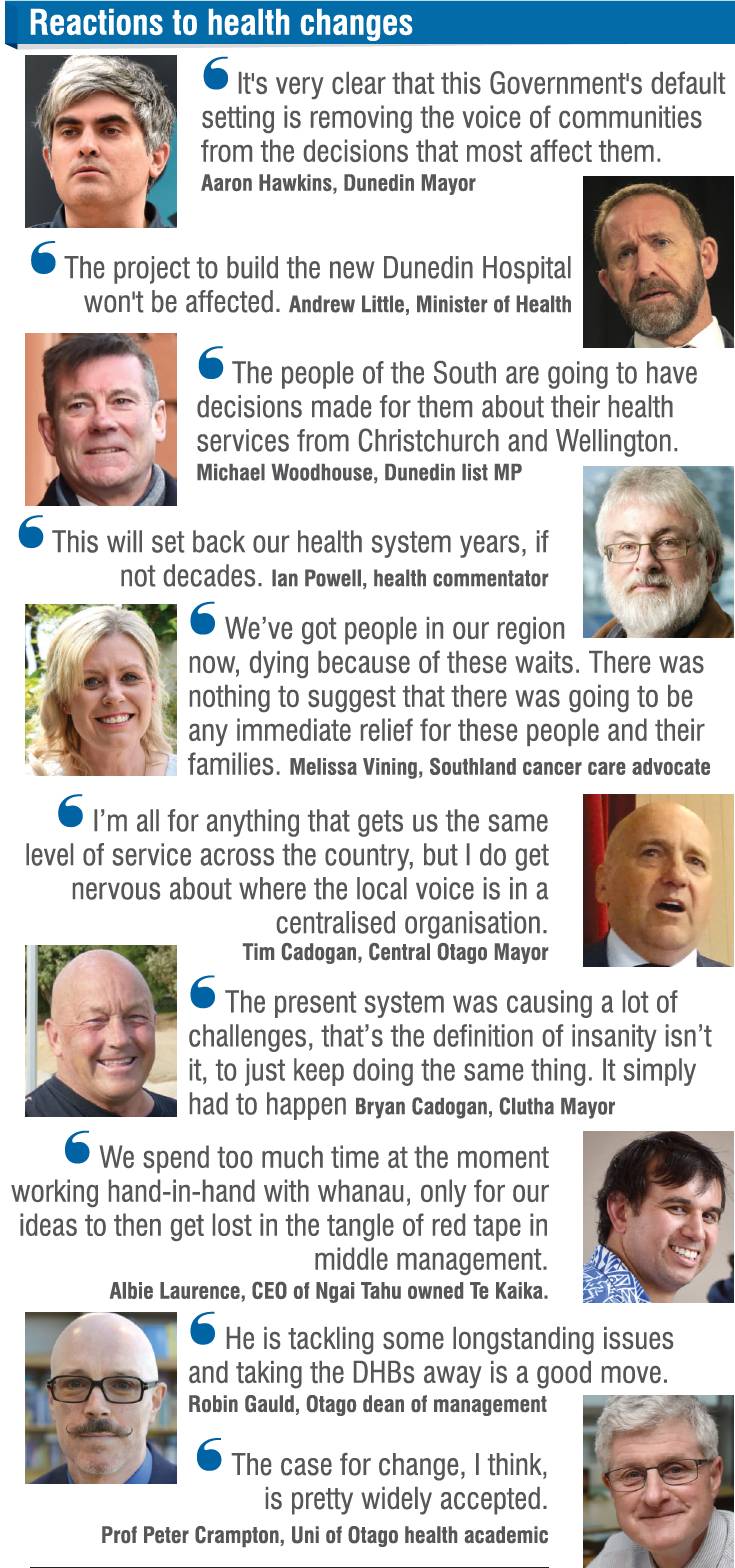

Health Minister Andrew Little yesterday announced a raft of changes to the health system, including the scrapping of all 20 district health boards in favour of one national organisation, Health New Zealand, by July next year.

It was a gratifying acknowledgement of the disparity of healthcare New Zealanders received based on where they lived, Ms Vining said.

But change needed to happen faster, and more people would die during the transition, she said.

"We’ve got people in our region, now, dying because of these waits, and there was nothing to suggest that there was going to be any immediate relief for these people and their families."

Ending the bureaucracy of having 20 different chief executives for 20 different DHBs was welcome.

"I think that’s a big part of why, for us in Southern, we get such a short end of the stick compared to the rest of the country."

People had to question the wisdom of a country of five million people having 20 health boards, Central Otago Mayor Tim Cadogan said.

But he had just returned to work after "top-rate" care in the current system.

He waited fewer than three months from cancer diagnosis to surgery, though it could have been that he had "the right cancer in the right DHB".

"I also appreciate that my experience is not the reported experience of a lot of people," Mr Cadogan said.

"I’m all for anything that gets us the same level of service across the country, but I do get nervous about where the local voice is in a centralised organisation."

While he could not comment on the details of the reforms, it was important all New Zealanders had equal access to health care, he said.

"The present system was causing a lot of challenges," Bryan Cadogan said.

"That’s the definition of insanity, isn’t it? — to just keep doing the same thing."

Waitaki Mayor Gary Kircher said most DHBs were running deficits and remote hospitals such as Oamaru Hospital had to fight for funding.

Still, the cost for people from the Waitaki, making multiple trips to Dunedin for care, remained high.

It was unrealistic to expect every area would have the same services, but it was important to make sure people further from main centres were given more priority, not less, Mr Kircher said.

In Lumsden, after losing a battle to stop a maternity downgrade, Gemma Sloane said she was on the fence about the reforms.

The Northern Southland Medical Trust member said she personally held fears that, with a more centralised system, rural areas with low populations might have less of a say in their healthcare.

But if there was to be an investment in primary healthcare, it would be better late than never.

University of Otago general practice and rural health department head Carol Atmore said the reforms had the potential to "strengthen the voice of rural communities".

Critical to the success of the new system would be the amount of funding diverted into primary care, Dr Atmore said.

"There are very willing people in primary and community services, who are working really hard, but they’re actually being asked to do more than they have got the resources to do.

"As services are being shifted out of hospital and into communities the funding needs to follow so the services can be provided."

Clutha Health First chief executive Ray Anton said the reform was bold, but well signalled.

"They’ve heard us when we talk about how rural seems to be the poor child," he said.

What the new system looked like, and especially how it differed from what was already in place locally, remained to be seen, he said.

Comments

Anybody who thinks moving to a Wellington-controlled centralised structure will improve things is ignoring centuries of history. NZ adopted a local health authority structure precisely because a centralised one wasn't working. And the government's shambolic performance with managed isolation facilities and covid testing hardly gives one confidence they can do this far more complex job.

I have gone half blind due to Dunedin DHB inaction. Seeing my symptoms not looking for cause over 20 years. Finally I went to Dr Google and 2 hours of research concluded gout can cause blindness. The Doctors are over worked they cant do good medicine seeing 50 patients a day. Ex Mayor Cull was Chair of the DHB is he being treated in the public hospital? No one responsible for running these should be able to opt out of the public system if they become sick. That would make them make it work.