The Christchurch arts scene of the 1930s to 1950s was comparable to the early 20th century English ''Bloomsbury Set'', author Peter Simpson claims in this comprehensive work.

BLOOMSBURY SOUTH: The Arts in

Christchurch 1933-1953

Peter Simpson

Auckland University Press

By JESSIE NEILSON

The Bloomsbury Set in early 20th-century England revolved around a loose group of artistic visionaries reacting against what they viewed as a hostile, deeply conservative old guard. The individuals were united by shared aesthetic outlooks and the urge to create and express in new, freer forms that more honestly reflected their realities.

Like this niche in England, the 1930s through to the 1950s saw an astonishing "efflorescence'', no less, in the arts based in Christchurch, encompassing literature, fine arts, typography, printing, publishing, classical music, and theatre.

Author Peter Simpson's claim is that the arts flourished in this time and place to such a degree to be considere comparable to the British Bloomsbury Set. He is a writer, scholar, and a graduate and past lecturer of the University of Canterbury.

With personal ties to Christchurch and a number of these individuals, he extensively delves into why this might have developed, and what factors then brought about the end of this "Golden Age'' for New Zealand arts and creativity.

To name this coterie as a Bloomsbury of the South is a bold statement, and one that he qualifies. While parallels can be drawn between the Woolfs, Bells, Strachey et al and their modernist innovations in the arts a generation before, each is distinctly flavoured. Bloomsbury was to be seen as a useful and positive model, but one to be adapted. He discusses the paradox of looking to overseas models while endeavouring to create the locally distinct.

Simpson urges New Zealand's loose group, while centred in Christchurch, to be viewed in its own light, as a national movement. It is to be held for its own accomplishments and expressions of a particular "New Zealandness'', often overly aware - without being derogatory - in its conscious (artistic) provincialism.

Simpson has an overflow of evidence to back up his claim: the establishment by literary giant Charles Brasch of journal Landfall (earlier proposed as Tuatara); poets Denis Glover and Allen Curnow and the Caxton Press; Canterbury College of Art graduate students and The Group.

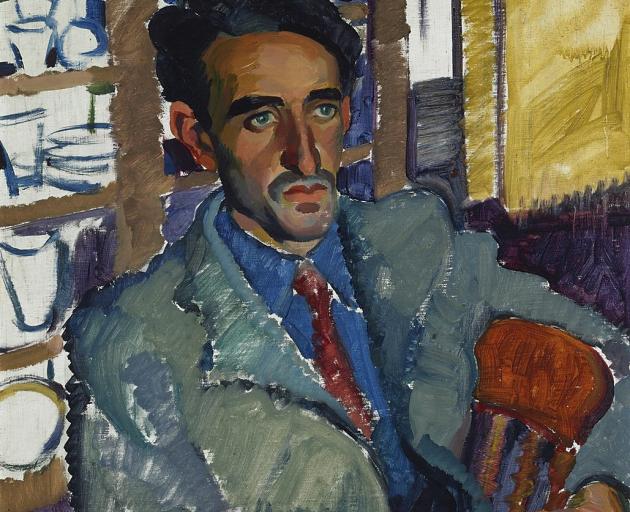

The backbone was the strong coterie of formative artists including Leo Bensemann, Rita Angus, Toss Woollaston and plenty more of great renown; emerging poets singing in new, brave voices; printers and artists experimenting with new forms; as well as Douglas Lilburn and his new directions in musical composition, and a new wave in live theatre and performance.

Crime fiction writer the chic, outlandish Ngaio Marsh, noted for her booming like the "proverbial bittern'', carved out a place with live Shakespearean drama. James K. Baxter was being noticed at this time also: as an 18-year-old in 1944 he was rather endearingly, and presciently, observed as one who would have to "boil hard and scrape the scum off his jam ... [which] promises ... to be good jam''.

Simpson's premise holds firm as he answers to it knowledgeably and soundly. He outlines how, as with Bloomsbury, this southern movement embodied innovative techniques and representation in the arts, rejecting stifling Victorian models that were mostly centred around realism and staid expression.

Literature in its new sights was broadly modernist in style, form, content and expression, while the visual arts embraced post-impressionism, for example in the works of Frances Hodgkins and Doris Lusk. Plenty of ire was raised by the "Establishment'' in a mutual hostility, where for instance, in shortsightedness, works by Hodgkins were to be turned down for purchase.

Simpson is comprehensive in making his links. These artists' ideologies, we learn, like their British predecessors were liberal, broadly socialist, and generally philosophical without a heavily engaged political focus (though, regarding war, in the main staunchly pacifist).

Simpson emphasises the importance for these members of interpersonal relationships and the intrinsic worth of the privacy of people and "things'' rather than their instrumental value. They believed firmly in the old adage "art for art's sake''. Sexualities and their practices were likewise liberal and non-conformist.

Simpson's extensive, hard-cover work is the first in the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Creative Lives Series and it is splendid. Generously awash with glossy photographic evidence, Bloomsbury South allows the curious reader to view stunning paintings by members of The Group, and their expressions of New Zealand landscapes. There are examples of Landfall covers and experimentation with layout, fonts and print; private correspondence wholly in verse between poets Curnow and Glover, and revealing photographs of the visionary individuals involved.

The book's format, while including the hybrid elements of inspiration and creativity, is clearly divided into nine broad chapters which each focus on different aspects of the arts, appropriately opening with poet Ursula Bethell, the "mother of all'', imperious at the same time as taking young artists under her wing; those "strong wilful wildings thirsty for direction''.

The last chapter focuses on the inevitable dispersal of these artists. A.R.D. Fairburn held that the New Zealand writer should be "willing to partake, internally as well as externally, of the anarchy of life in a new place and, by its creative energy, give that life form and consciousness''. This could perhaps hold as true of all the artists contributing towards what can aptly be considered as Bloomsbury South.

Jessie Neilson is a University of Otago library assistant.