It was a blockbuster show with a cast of thousands and crowds of millions. Paul Gorman looks back 100 years to the New Zealand International South Seas Exhibition.

It was a "perfect summer’s day, with cloudless skies and blazing sunshine" for the official opening of Dunedin’s biggest-ever event — which would in time be visited by the equivalent of almost three times the population of New Zealand.

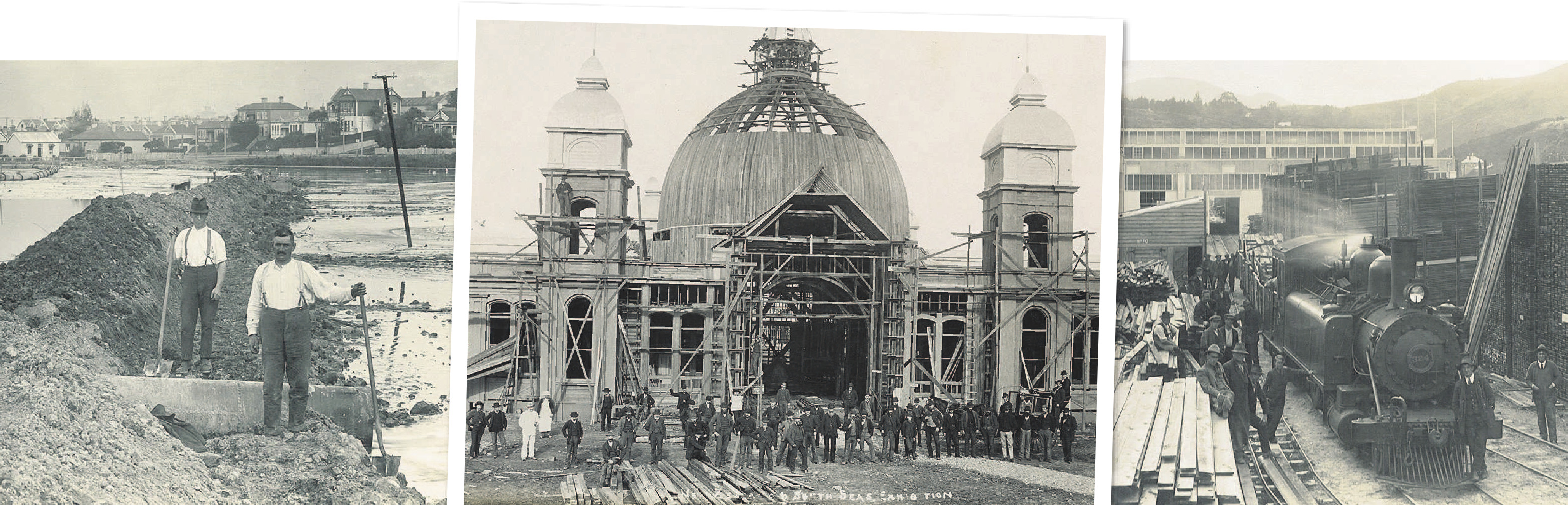

At midday on Tuesday November 17, 1925, the gates of the New Zealand and South Seas International Exhibition of 1925-26 were unbolted and people began streaming in to the newly drained Logan Park.

The Official Record of the exhibition could be forgiven for some hyperbole about the weather amidst all the excitement, but conditions were pretty much as it stated on that special day. The Otago Daily Times the following morning confirmed benign weather across the city on Tuesday: "Bright and fine. Fresh south-west wind. Max 67°F [19°C]."

According to the Official Record, "an hour before the time fixed for the beginning of the ceremony [2.30pm], the greatest public assemblage ever seen in the history of Dunedin had already filled the Public Grand Stand and was rapidly occupying every vantage point in the enclosures".

"The scene outside the Exhibition gates at about 2 o-clock was one not easily forgotten."

The Times’ editorial that morning put the exhibition in perspective, saying it would "signalise a very striking landmark in the history of the city of Dunedin, the Otago province and indeed the Dominion as a whole".

"Not many people are alive today who remember the opening of the first Exhibition in King Street, though the building, happily devoted ever since to humanitarian purposes, still stands as a memorial of an enterprise which was very creditable in view of the fact that the Otago settlement was only in its eighteenth year at the time.

"Memories of the second Exhibition are more vivid, though a large proportion of the prominent personages of 1889-90 are no longer with us, and the school children of that period have now reached middle-age.

"The third Exhibition in Dunedin will naturally be on a much larger scale, symbolising the industrial, commercial, and social progress of three and a-half decades.

"The external features of the city may not have changed during the last thirty-six years so much as they changed between 1864 and 1889, but there has been an enormous development of business activity and commercial life, which will be fully exemplified at Logan Park during the next few months."

Festival co-ordinator Jonathan Cweorth says the occasion will also celebrate the 160th anniversary of the 1865 New Zealand Exhibition.

Among the plans are science tours of the Logan Park site.

"We hope to include some IT resources to bring it alive, because there’s not much physically surviving there at the moment, and that could include things like a QR-code treasure hunt, where people can go around parts of the site and read information on what used to be there.

"We’re also working with the IT department at the [Otago] Polytech on some sort of virtual-reality experience in which people could go there and physically see, in virtual reality, what was there before."

There will also be talks about the exhibition, including one from Heritage New Zealand adviser Alison Breese on what it took to build and develop the site, "an extraordinary feat of engineering and construction".

"We will also look at the broader cultural impact of the exhibition. For instance, the artworks that were shown there then fed into the city’s public art collection and also the collection at Olveston. And we’ll be looking at how the funds from the trams helped to build the Town Hall."

The demolition of most of the buildings at the end of the event was part of the culture of such exhibitions, Cweorth says.

But where did all that wood go? According to a display board in Toitū, more than five million feet of New Zealand imported timber was used — "specifically 4,624,624 feet (1410km) of red pine and 751,170 feet (229km) of Douglas fir".

"It would be interesting to know," he says. "No doubt it was reused, so there’s probably a few houses around Dunedin that aren’t aware that they’re built out of the remnants of the exhibition."

There were strong socioeconomic reason for the exhibitions.

"We feel there’s a relevance to the present day too, that this is a good time for Dunedin to be reminding itself of its strengths as a city, and to be using that commemoration of the great exhibition as a source of civic pride, both in the past and in the present."

The 1925-26 exhibition was huge for Dunedin and huge for the entire country.

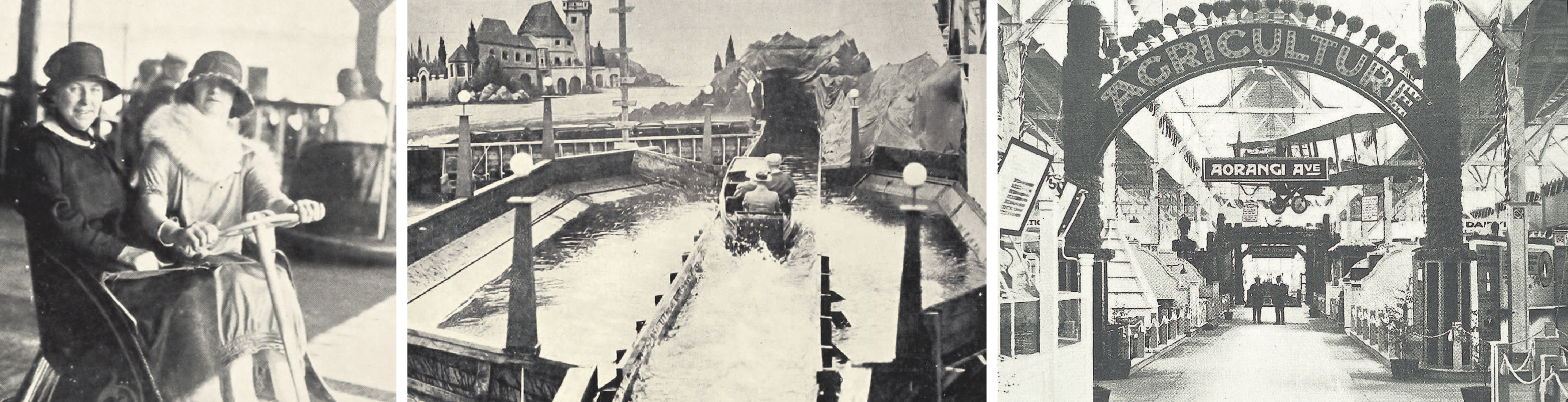

The other structures, including the impressive Edmund Anscombe-designed domed Festival Hall which linked with his seven pavilions on the more than 6ha site, as well as the amusement park, have long since gone, dismantled after the exhibition’s six-month run.

Many families in Dunedin and around the country still have mementoes from the exhibition, especially engraved items or pieces of cut glass, bought as keepsakes.

Dunedin author and publisher Brian Miller has a deep family connection to the 1925 event. He has written about it and given lectures on the Bazaar and Industrial Exhibition of 1862 and on all the city’s three subsequent great exhibitions.

The first, the New Zealand Exhibition of 1865, ran for five months, with about 800 exhibitors and a total attendance of close to 30,000 people.

The 1889-90 New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition also ran for five months. Its 300 imported artworks from Europe became the basis of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Total attendance was around 625,500.

The 1925-26 exhibition attracted 3,200,498 visitors, many of whom would have had a season ticket, at a time when the population of New Zealand was about 1.25 million.

"This was a huge undertaking, involving support from business, local authority, government and the community. It was an opportunity for Dunedin companies to show off their products to an international audience, and included numerous attractions, including a huge amusement park," he says.

"He grew up in a family of tradesmen. His father was a coachbuilder, of hansom cabs and cable cars, and his grandfather built houses.

"In 1911, Oswald set up a signwriting business on his own. He was soon recognised as the highest quality signwriter in Dunedin — the saying in Dunedin was that ‘Oswald set the standard’.

"There is no official record of Oswald getting a contract for the Logan Park exhibition, but his reputation was such by then that it is ‘assumed’ by the family that he was the leading signwriter. He bought a house to live in a block away from Logan Park, but even set-up and lived in a tent inside Logan Park at times, so he was available at any time."

After the exhibition, his grandfather built a new house in Dundas St, bought an American car and put up a crib at Brighton.

"He also set up new premises in Rattray St — next to Robert Fraser, the first stained-glass artist in Australasia, who Oswald probably worked alongside at the exhibition.

"Oswald’s sons Roy and Ralph became involved in the business. It was certainly the leading signwriting business in Dunedin and remained that way until it folded during Covid."

A lot of signwriters from those days died early due to the chemicals they had used and the lack of protective gear, Miller says.

"Oswald got dementia in his 60s and died in Seacliff hospital, probably due to mixing white lead paint by hand every morning as a basis for the day’s sign painting. There were no ready-made coloured paints — you had to mix in the colours every day you thought you would need."

Miller heard his great uncles and aunts talking a lot about the exhibition and the family’s links to it. His aunt, Doris Inglis, who died in April, had her first birthday on the day the exhibition opened.

The three exhibitions all took place on the back of significant, wider socioeconomic events, he says.

The 1865 event was organised in the flush of confidence following the 1861 gold rush, while the 1889-90 exhibition was held in an attempt to revitalise the city and region after the end of a long decline during the depression of the 1880s.

By the mid-1920s, there was again a feeling that other cities were progressing faster than Dunedin, which was being left in the doldrums as a financial centre as business drifted further north.

With a gobsmacking 20,000 people a day on average visiting the exhibition, Dunedin faced considerable logistical challenges, especially around transport and accommodation.

Visitors from around the country travelled by rail to Dunedin, while those from overseas, notably Australia and Europe, arrived by ship. Well-to-do locals came by car, but most used trams on a new line running along Albany St right to the gates of the exhibition venue, Miller says.

Anzac Ave was constructed especially for the exhibition, as the highway taking visitors directly from the Dunedin Railway Station to Logan Park.

One of the remaining puzzles is where all the visitors stayed.

"That’s what nobody really seems to know. But it would be interesting to find out."

On opening day, the Times said guests at the Grand Hotel included prime minister the Hon J G Coates and Mrs Coates, Mr and Mrs Andrew Fleming from Gore, and Mr and Mrs Simpson from Melbourne.

The Carlton Hotel had among its residents a Mr and Mrs le Patourel from Guernsey and Mr A J Tanner from Sydney. At the Excelsior Hotel was Mr H P Ritchie from Samoa, and Mr J W Calder and Mr W T Evans from Lincoln College, among others.

Mr P W Truesdale from Vancouver was one guest staying at Wain’s Hotel, while Mr L Pavletich of Hakataramea was one of five at the City Hotel.

All good things come to an end. Unlike the sunny summery day which greeted crowds when the exhibition was opened, the closing ceremony on Saturday, May 1, 1926 took place amidst "steady rain and heavy skies", according to the Official Record.

"It had been intended to hold the closing ceremony in the afternoon on the sports ground, and to have troops and city bands in attendance; but the well-arranged programme had to be modified.

"The ceremony was held in the Festival Hall, which was packed to the doors within a few minutes of their opening ... outside in the Grand Court another huge crowd stood under their umbrellas around the rotunda, where ‘loud speakers’ broadcasted the speeches."

The ODT of Monday reported that on that rather grey closing day, the city had a maximum temperature of just 46°F, about 8°C.

The Times also published the attendance register for all 24 weeks of the exhibition. In the first week, 114,411 people visited and in the last week there were 265,357 who went through the gates.

The largest attendance of 83,935 was on closing day, while the smallest of 9087 was on December 7, 1925.

Among the many poignant words in Monday’s paper was the lead story:

"The end of the New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition, 1925-26, has come at last. During the past five and a-half months the great enterprise has gained such a place in the lives of the people that many have come unconsciously to accept it as a permanent part of their existence. It was only a week ago that they suddenly awoke to the realisation that the inevitable end was at hand. Then they began to crowd down with renewed eagerness in their tens of thousands till the great climax was reached on Saturday.

"If the weather for the opening of the Exhibition on November 17 was as propitious as it well could be, the conditions for the closing Saturday could hardly have been worse. Rain fell heavily the night before and all Saturday a steady drizzle saturated the air and turned the paths of Logan Park into chains of muddy pools. But what matter? The success of the Exhibition was long ago placed beyond any doubt, and no

rain could deter the people from paying their last tribute to the great achievement in which they, too, have had their part."

The passion carried on in the editorial:

"The transformation of Logan Park into an environment worthy of its purpose has been in itself an object lesson. The New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition has been an event in the life of the Dominion. It has made history. That, as a landmark in the story of the country’s progress, it should be made a stepping-stone to higher things is not more than should be reasonably expected."

So, was the editorial right? What was the enduring legacy of the event?

Jonathan Cweorth says the paper’s assessment wasn’t entirely misplaced.

"The exhibition had a lasting physical and cultural impact, insofar as it left as a legacy Anzac Avenue, Logan Park, the city’s first public art gallery building (and much of its collection), and funds to build the Town Hall," he says.

"At the time, it was the biggest event in New Zealand history, and was regarded as a major cultural and financial success, retaining visitor interest until its very last days, which still drew record crowds.

"If we think of the civic pride Dunedin currently gains from a major international act appearing at Forsyth Barr stadium, I’m going to hazard a guess that the exhibition had the morale-boosting effect of six months’ worth of Ed Sheeran concerts."