In common with many aspects of our creaking health system, the pressures resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic response exacerbated issues which already existed.

It has been known for years the ageing workforce of general practitioners was a problem and that there was a need to attract doctors to rural practices. Doctors from overseas doing stints in practices here slapped a Band-Aid on the sore, but border closures and the worldwide shortage of health professionals have revealed the festering.

There is no quick fix for the longstanding shortages in our homegrown workforce, no matter how much we might all want there to be. Thinking that propping up our services with professionals trained elsewhere is the answer is unrealistic when many countries are facing similar shortages too.

As far as GPs are concerned, it takes between 11 and 14 years to become a specialist general practitioner, and although we need to train 300 doctors to enter that specialty annually to maintain the status quo, fewer than 200 a year are being trained. There has also been a pay gap between those doing hospital-based postgraduate training and those training as GPs, which is only now being addressed. The Government does not yet seem to have cracked developing a cohesive response to the health workforce crisis.

Its recent announcement of a $200 million a year funding boost to give front-line community health workers pay parity with their counterparts in public hospitals did not include those working in general practices.

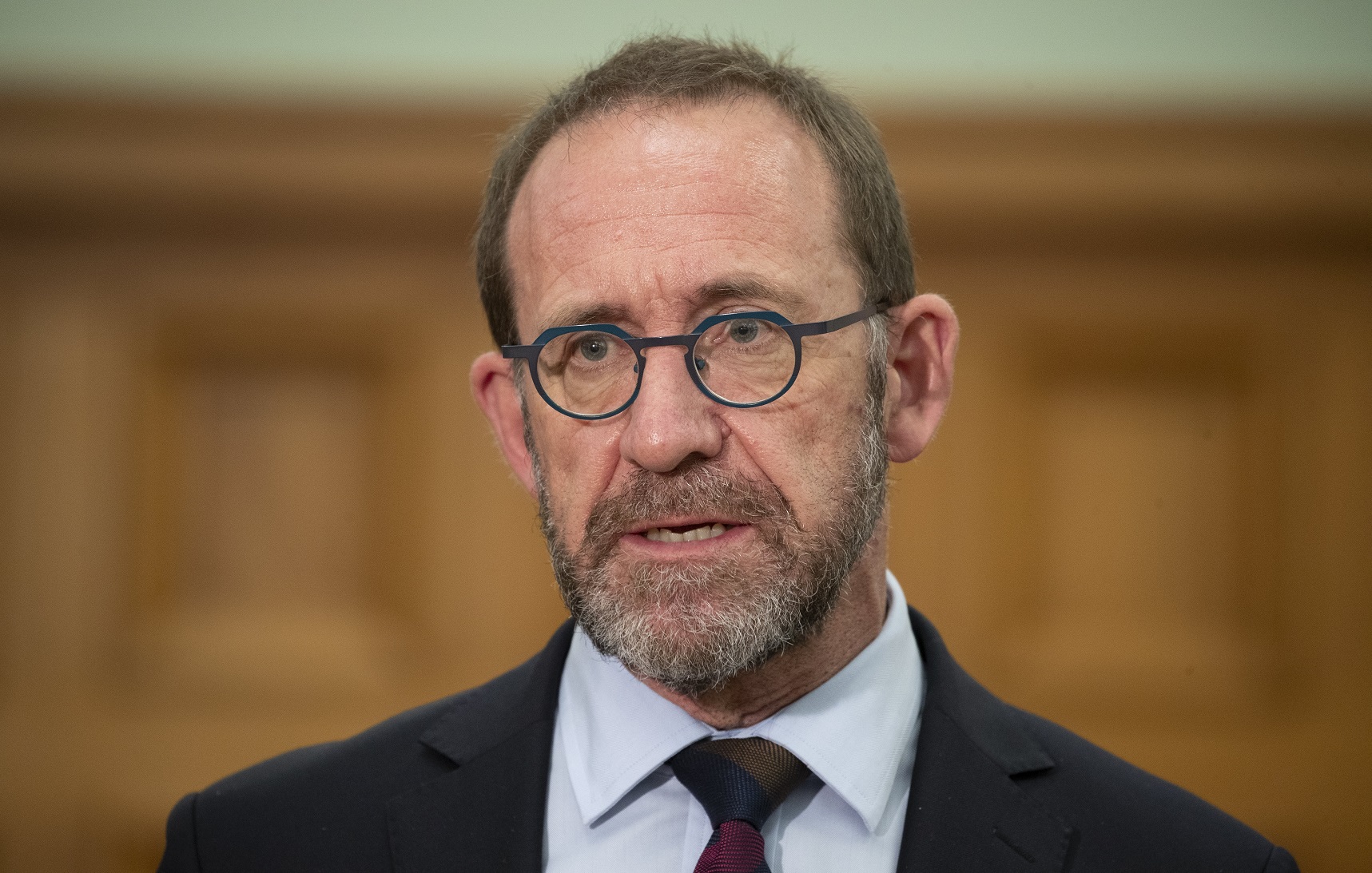

Health Minister Andrew Little was not convinced he had data showing "any real evidence" of a pay difference.

This is disputed by the sector, which reckons GP nurses are being paid on average $8000 less a year than public hospital nurses.

It is understandable general practices are upset, given the pressure their staff have been under and the role they have played, and continue to play, in the pandemic.

It is a messy situation which surely could have been avoided and needs to be addressed quickly.

This month, a proposal for boosting medical school numbers for the training of rural GPs will be put to Mr Little.

The Rural Health Network — Hauora Taiwhenua, with the support of the Royal College of General Practitioners, and both medical schools, is proposing a pilot scheme which would offer up to 50 placements for training rural doctors in their local area.

The rationale is that by training students in rural areas you are more likely to retain them there when they graduate. Much of the training would be done by distance learning with block courses at main hospitals.

Rural academics from the medical schools at Auckland University and the University of Otago would form a joint department of rural health, with a team of part-time teachers and researchers in rural areas able to train people locally, the network’s chief executive Grant Davison told RNZ.

One of the issues which has been identified by the network is that the NCEA results in rural areas are limiting the pool of prospective students.

Part of the proposal would be putting extra science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) training into schools with mentoring to help senior pupils reach the level where they could qualify for entry into medical school. Those behind the proposal are confident it could be set up quickly if the funding is provided.

If the scheme is successful, it will not be an overnight solution to the rural GP shortage, but it is an innovative, sensible and holistic approach to the issue which we hope Mr Little will give the serious and urgent consideration it deserves.