Why were the Anzacs at Gallipoli?

The Ottoman Empire was not part of the deadly twin daisy chains of alliances and obligations that dragged all the other great imperial powers of Europe into an involuntary state of war in the days after the Austro Hungarian-Empire chose to attack Serbia.

The convoluted and sometimes ridiculous story of how the Ottoman Empire became the Anzacs’ first enemy involves pride, greed, incompetence, insubordination, brilliant opportunism and desperate decisions made in haste with little information. Above all it involves battleships, the great floating fortresses that so disastrously possessed the minds of great men in the first decades of the 20th century.

As that century opened a four-cornered dreadnought battleship building race was going on between Germany, Britain, the USA and Japan. Germany and Japan were able to pursue their naval buildup steadily and in a carefully planned manner. In the USA and Britain periods of political complacency when shipyards were starved of orders for battleships alternated with periods of popular panic, meaning that demand for ships had to be smoothed out.

Exporting battleships to third countries was one way in which this could be done, and salesmen fanned out from the British and American yards, backed both by diplomacy and enormous sales budgets. The battleship barterers identified the volatile new nations of South America as the prime market for British and American battleships.

Seven dreadnoughts were sold to these three countries in less than three years. Brazil agreed to buy three dreadnoughts from Britain in 1906. Argentina and Chile promptly responded by each ordering two larger ships: Chile’s from Britain, and Argentina’s from the United States.

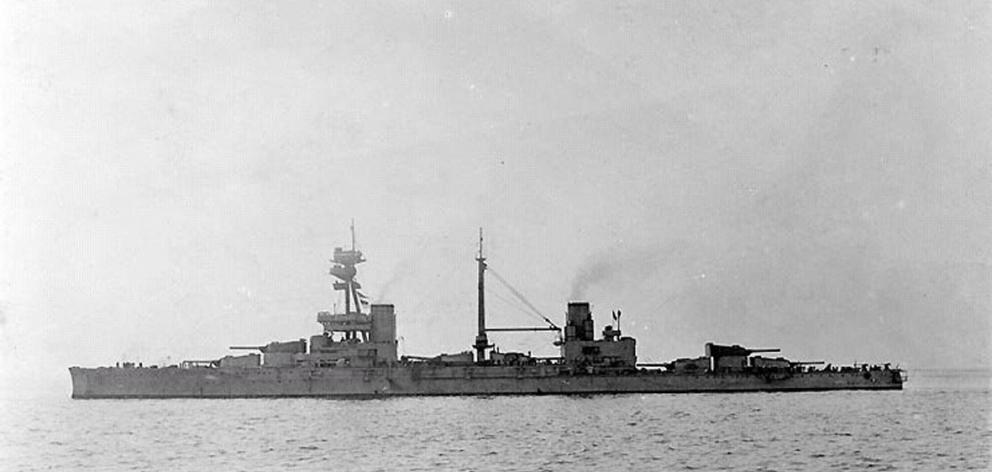

By 1908 the South American battleship buying fever was cooling rapidly in the face of the staggering costs and risks of escalation. Brazil tried and failed to extricate itself from its commitment to build the third battleship Rio de Janeiro that it had ordered from the British Eventually, with British help, the Brazilian government onsold her to the Ottoman Empire in 1913 for $6 million while she was still incomplete. The Rio de Janeiro became the Sultan Osman I. The ever-active British dreadnought salesmen also sold another larger and far more capable dreadnought, Resadiye, directly to the Ottomans.

Although Sultan Osman I was the weaker unit of the two new Turkish ships, the situation within the Ottoman Empire at the time of its acquisition endowed it with a much greater political importance to the Turks.

The Turks were aware that the Ottoman Empire’s neighbours harboured further expansionist ambitions that would potentially leave them entirely partitioned and occupied. This was a national rather than government realisation. As the government was both chaotic and destitute, the Turkish nation raised the money to buy the Sultan Osman I by public subscription.

The significance of the gesture was acknowledged by the new ship’s name, that of the Ottoman Empire’s founder.

The nine months between the sale of the Sultan Osman I to the Turkish Empire, and the outbreak of war passed in a frenzy of dreadnought building. By August 1914 Great Britain had established a lead over Germany of 29 operational capital ships to 17. Nevertheless, this numerical advantage brought no comfort to the British Admiralty, who found themselves in a novel and terrifying position.

For centuries the Royal Navy had enjoyed a man-for-man combat superiority over their opponents that had led to a complacent expectation of victory.

In August 1914 that comfortable British mindset was gone.

Within the lifetimes of the admirals that led the fleets on the eve of war, guns had advanced from devices that could waywardly deliver a cricket ball-sized solid shot a few hundred yards, to guns that could accurately deliver high explosive shells that weighed more than a tonne to a target some 15 miles away.

Nelson had approached Trafalgar with an assurance built upon a deep experience of combat command involving ships in whose superiority he was completely confident.

Jellicoe, his successor in command of the British Grand Fleet, had no such luxury.

Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, rightly remarked that Jellicoe was: ‘‘ ... the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon’’.

The atmosphere of naval apprehension caused Churchill to make a fateful decision.

On August 5, the day after war broke out, he ordered that all dreadnoughts under construction in the UK for foreign powers were to be acquired immediately and added to the British fleet.

The Turkish ships were both seized.

The incomplete Resadiye was seized on the slipways in a smooth paperwork manoeuvre and renamed HMS Erin.

The takeover of the newly completed Sultan Osman I was a far messier affair.

The Turkish crew was already in Newcastle prior to the official handover.

On hearing that this was not going to happen, the Turkish Admiral in command stated that he and his crew would depart with their purchase.

Churchill ordered that any such attempt was to be resisted with deadly force if necessary.

It seemed that the Great War might start with an action between British and Turkish battleships in the middle of Newcastle.

Fortunately, the matter was resolved without bloodshed and the Sultan Osman I became HMS Agincourt.

The humiliated Ottoman government refused to accept a refund of their payment for the two ships, holding them to be stolen property.

The seizure of the two dreadnoughts caused great anger throughout the Ottoman Empire, but it did not lead immediately to war.

The aging Sultan, Mehmed V, refused to ratify a German alliance, but the seizure of the two ships by the British led to intense pressure upon him to do so — which he resisted.

The Ottoman Empire was balanced upon the brink of war.

It would be the activities of yet another dreadnought that would push her over the edge and into open conflict.

Continued tomorrow.

■Dr Robert Hamlin is a senior lecturer in the marketing department at the University of Otago