How else to explain the lack of outrage from our law-and-order-obsessed government about Statistics New Zealand deciding not to fine anyone for not taking part in the 2023 census?

The decision was announced a few days after the 2023 election so perhaps our soon-to-be Beehive dwellers had bigger things on their mind.

In the normal course of events, between 30 and 60 people are usually prosecuted for refusing to participate in a census, an offence with a maximum fine of $2000.

Such prosecutions focused on those who were threatening to census staff and those who actively encouraged others not to participate.

But after the 2023 census, it was discovered the requirements of the request for data section of the Data and Statistics Act had not been met, so there was a risk charges would have been challenged.

Not a good look for a department we would expect to act with precision at every turn.

It was a small illustration of the shemozzle censuses have become here.

In 2018 we had the failed experiment of the online census and in 2023 costs ballooned again amid other issues including whether people’s privacy was properly protected in some instances.

However, taking the step of abolishing the traditional census in favour of, as yet not fully explained (or costed as far as I can tell) gathering of administrative data and surveys, is an extreme response.

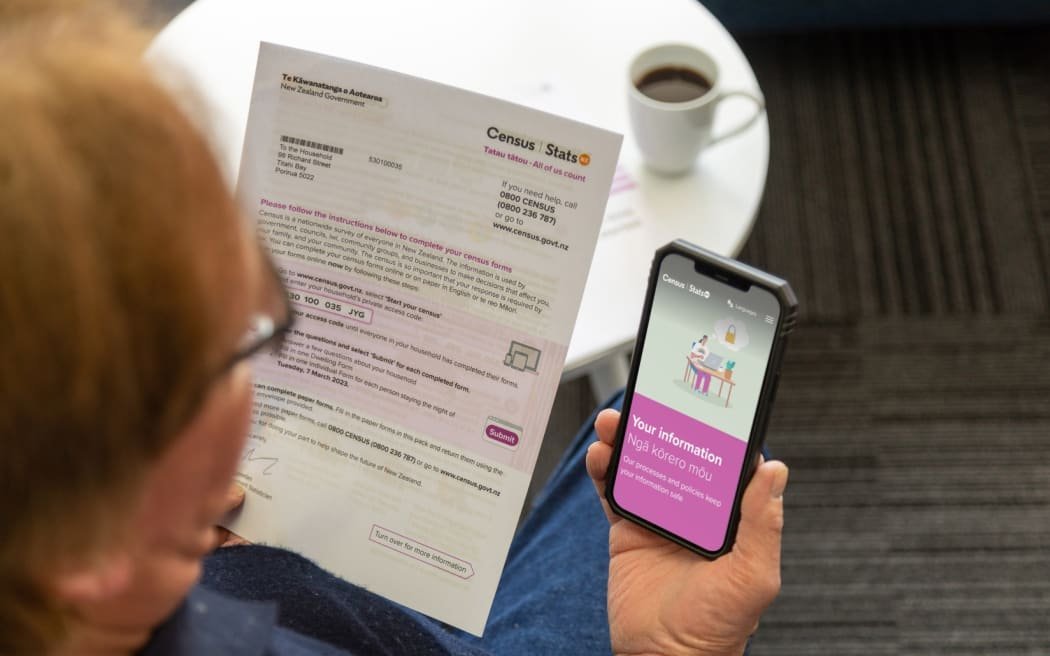

It might be a relief to some to know they will be no longer obliged to fill out the five-yearly questionnaire.

We might have sometimes struggled to find the forms days after they had been delivered and decipher them through the tea/coffee stains, muttered about the purpose of some questions and, in my case, been stumped trying to explain something as basic as the rooms in my house.

But do we really know the impact of not having such detailed door-to-door gathering of information?

Information from the traditional census has been used to help decide how resources should be distributed in health, education, and other major government agencies, and for determining electoral boundaries.

Questions have been raised about the information to be used in the next review of boundaries, due in 2028, when the revamped census will not eventuate until 2030.

Authorities on matters statistical, including the redoubtable Len Cook (former chief New Zealand and United Kingdom statistician) and Massey University sociologist Professor Paul Spoonley have expressed serious reservations about the census scrapping and the likely quality of the alternative.

Mr Cook has gone as far as calling for an independent review of the census change by the Royal Society of New Zealand to assess the scientific integrity and validity of the new approach.

Among concerns are that Māori and Pasifika, undercounted in the last census, and low socio-economic and rural areas will be adversely affected by the changes.

We do not know what gaps there will be in the administrative data — information already collected by government agencies.

Details about anybody who rarely comes into contact with a government agency will be scant.

Will it be a case of "not knowing what you don’t know"?

Those of us with experience of wrestling information out of government agencies might wonder how good all of their systems are at collecting data accurately and passing it on as might be required.

A recent experience of mine at Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand, involving the Official Information Act, is a case in point.

I have been waiting since early April for information about waiting times for urgent, non-urgent and surveillance colonoscopy waiting times at Southern, after I pointed out they were absent from a web tool listing all other areas’ waiting times.

In late May I was told the data had not been submitted after issues following transition to a new patient information care system.

Late last month, still no joy. I was told responding to my request had "taken much longer than anticipated, for which we offer our sincere apologies. The time taken is not what we aspire to." Good grief.

In the new-style census, annual surveys are supposed to fill in some of the blanks from the administrative data, but we do not know what questions these will ask. It is unlikely sample sizes will be large enough to drill down fully into small communities.

Will those people reluctant to participate in the census because they did not trust the system, be any more enthusiastic about these surveys? It seems the surveys will be compulsory to complete, if you are chosen, and subject to the up to $2000 fine if you refuse.

If the new system turns out to be a dud and about as reliable as commentators trying to guess the score of the next All Blacks’ test, what next?

• Elspeth McLean is a Dunedin writer.