One day in the winter of early 1917, New Zealand troops in northern France might have been surprised to see a distinguished visitor in civvies confidently striding about the place, chatting away to generals and privates alike and dismissive of the usual military conventions and courtesies.

The visitor knew what he wanted and was determined to get it. It was the story of his life. The visitor was Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, otherwise known as Lord Northcliffe and soon to be known as Viscount Northcliffe.

He was the shrewd businessman-journalist who put the fleet into Fleet Street — who transformed the British newspaper world by starting the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror, then extended his control by buying such august titles as The Times and the Observer.

A man of wide influence and political power, during the war he still liked to get out and do the job he’d been doing since he was a teenager: being a journalist, even though he employed hundreds.

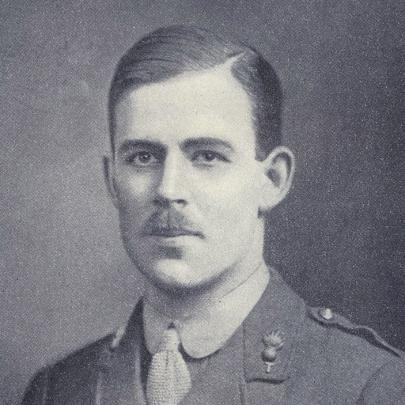

One of his employees at The Times was Dunedin-born Noel Ross, a sad and typical example of a promising career destroyed by war. Ross had been among the first New Zealand troops to land at Gallipoli in April 1915, and was wounded and evacuated to Alexandria, in Egypt. He was eventually sent to hospital in England and told he was no longer fit to be a soldier. He joined the British army but it would have him only as an instructor. So he turned to journalism, the profession in which he had made his first tentative steps in Christchurch before the war.

It was probably an advantage that his father was Malcolm Ross, the official New Zealand war correspondent who had worked for the Otago Daily Times. He had also been the local correspondent for The Times, so there was a toe, if not a foot, in the door at Printing House Square. But young Ross also had the talent.

A yet-to-be-convinced news editor dispatched him to rural Surrey to cover a gathering of cycling history enthusiasts, the sort of assignment in wartime given to the lowliest of the low. The copy he handed in found its mark and Northcliffe noticed.

"I am glad," he wrote, "to find in these days of depleted organisation that we have a new writer in Mr Ross ... His account of the ‘Pilgrimage on Wheels’ this morning shows a deal of knowledge on an almost forgotten subject."

An indication of Ross’ enhanced status was that he accompanied King George V on one of his visits to the Royal Navy fleet at Scapa Flow. It cannot be known for sure, but it seems likely, even probable, that Northcliffe spoke to Ross before deciding to go to France and do some reporting himself. Northcliffe was conscious some of the national armies in France and Belgium, especially New Zealand’s and Australia’s, were not getting the publicity in Britain they should. It surely was no coincidence that when Northcliffe showed up at the headquarters of the New Zealand Division, among the first to greet him was Ross’ father, Malcolm.

Northcliffe had lunch with the division commander, General Sir Andrew ("Guy") Russell, and was shown around the areas of New Zealand’s responsibility, "amidst the muddiest, floodiest scene imaginable. Streams had swollen into rivers and rivers into lakes."

Northcliffe’s dispatch appeared in The Times on January 29, 1917, and was headed: "The tall New Zealanders. Their life at the front. A very complete little army."

It was a column of praise for New Zealand and New Zealanders, from the distant that Northcliffe had not seen (brown trout as large as salmon, stags that make the Highlands species look like dwarves), to the present that he had seen just briefly.

"... A student of the New Zealanders gets a very fair idea of what a model British army should be, how it should be provided with a sufficient number of officers trained to the difficult task of staff and intelligence work, how the officers should be to some extent promoted from non-coms, and how care should be exercised that the ranks of the non-coms be not entirely depleted of their best men."

Northcliffe gave an idea of the extent of the New Zealand presence.

"The New Zealanders occupy a fair stretch of the front line, and their billets, rest camps, lines of communication and bases go a long way back. They therefore form a New Zealand world of their own, and the average French peasant, who had never heard of a New Zealander before, knows all about them now and likes them. For the war has placed New Zealand on the map, as the Americans say, with a prominence that could not have been obtained by any other means."

Northcliffe learned a little more about a part of New Zealand when he briefly visited Auckland and Rotorua in 1921 as part of a world tour that was mainly designed to restore his health after he had been affected by a blood infection. It was to no avail because the infection spread and he died a year later, aged 57. Known as The Chief, he was described as the greatest figure who ever walked down Fleet Street.

Noel Ross did not see the war out. He died of fever in December 1917, aged 27, his parents saying his constitution had been so weakened by his Gallipoli wounds that he had little resistance. For one so young and inexperienced, and previously a mere private, his death had an unusual impact. The editor of The Times, Geoffrey Dawson, received a message from Buckingham Palace: "The King was grieved to read in this morning’s Times of the death of Mr Noel Ross ... His Majesty knew him well and was always impressed with his personality."

A telegram of sympathy arrived from Rudyard Kipling, who had talked to Ross of the writing of Puck of Pook’s Hill. Northcliffe said in a message to Times staff: "We have had a very severe blow in the death of dear Noel Ross, who was akin to genius."

Ian Hamilton, the general in charge of the Gallipoli campaign, had known Malcom Ross and met Noel in London during 1917. He wrote, the general of a private, to Malcolm and Bessie Ross: "The chief attraction (amongst a multitude) of your boy to me lay in his intense vitality, and although that was no shield against shells or bayonets, it makes it yet more natural and yet more cruel that his young life should have been cut short by an ordinary illness. I had something of the same feeling with regard to that splendid figure of heroic youth, Rupert Brooke, of who your boy so often and in so many strange ways reminded me."

- Ron Palenski