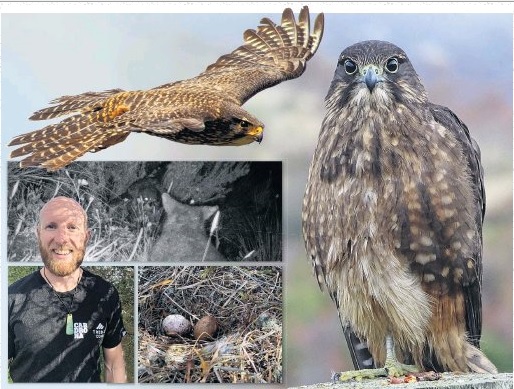

About 40 people turned up, to hear Graham Parker, from Parker Conservation, talk about how he planned to survey the karearea (or eastern New Zealand falcon) over the next three years in the tussock grassland mountain ecosystem.

Not only were the participants enthusiastic, but as if on cue, a karearea flew through the garden of the hotel while Mr Parker was delivering his talk.

"It was incredible — we couldn’t have scripted it, it was quite spooky," Mr Mackie said.

Department of Conservation’s karearea expert Dr Laurence Barea said very little was known about how the karearea might use different habitats within the alpine environment, which are most important, and why.

"Most of the focus of karearea research has been in the North Island in recent years, so the Cardrona project was quite unique."

Mr Mackie said the crux of the project was to get a really good scientific understanding of how these birds "get on in the alpine area," with a view to introducing a conservation plan.

Karearea is New Zealand’s largest bird of prey, and can fly at speeds of over 100kmh.

The conservation status of karearea nationally is now "recovering", with the population estimated to be around 5000-8000 birds nationwide.

Karearea usually nest by making a scrape on the ground, under a rocky outcrop or sometimes a tree.

The main threats to their survival are from predators eating their eggs, electrocution by electrical infrastructure, rotating turbine blades on wind farms and shooting.

In his report, ornithologist Graham Parker said the most important information they learned in this first year of monitoring was breeding started earlier than expected, with one pair laying eggs in September.

Between October 15 and December 13 they surveyed a section of the valley for karearea and found two breeding pairs of karearea.

One pair was breeding near the township, but their nest could not be accessed as it was on private property.

Mr Parker believed a nest in the back country this season most likely failed due to repeated possum disturbance.

"Once we have a more robust number of nests included in our observations, we can then better target management actions such as targeted predator control."

The other pair nested in a large old tree stump and did breed successfully, but the chicks were too independent to catch and tag for future monitoring, he said.

As a consequence, the survey would start earlier this year and cover a much greater land area

Mr Mackie said he planned another public meeting at the end of winter or early spring to "re-cap, reconnect and inform" the Cardrona Valley locals.

Comments

From what I've seen I would have said cars and secondary poisoning were their main killers. Or it that a different hawk?

The Kahu or Australian Swamp Harrier is the largest non-extinct native raptor, not the smaller and faster Karearea. The Kahu as a scavenger is the one most at risk from car strikes as they eat road kill. If you see dead wildlife on roads you can do the Kahu a favour and move the carcass to the verge.