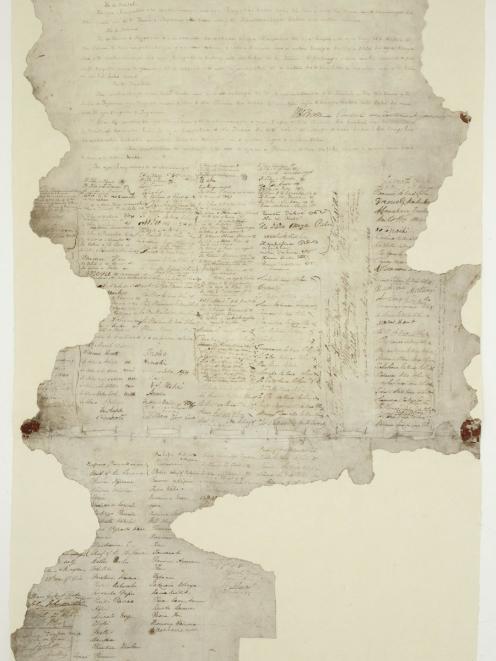

Te Tiriti o Waitangi has come in the past few decades to hold a central place in official New Zealand thinking, in legislation and in mandated mainstream discourse.

It has come to be widely accepted as the nation’s "founding document", and the "principles" of Te Tiriti as outlined by Justice Robin Cooke in the Court of Appeal in 1987 and by judges in later decisions, have come to the fore.

The Treaty, Maori perspectives and Maori involvement in what is, in essence, a 21st century Western world view and system, are bit by bit being introduced, including inching towards "partnership" and increased Maori sovereignty.

One of the latest moves, this week, was the announcement the Government will abolish the law that allows local referendums to veto decisions by councils to establish Maori wards.

For many, this is justice at work, slow progress towards fairness and Maori participation, chipping away at the monocultural post-colonial attitudes, practices, structures and governance.

Crucially, it is seen as what the Treaty promised. When matters and questions arise, they are confidently referenced back to the Treaty as well as to clauses about the Treaty in legislation. Parliament and a liberal judiciary have been reinforcing the place of Te Tiriti.

Interestingly, University of Otago law professor Jacinta Ruru and Court of Appeal judge’s clerk Jacobi Kohu-Morris, formerly from Dunedin, in an article published this week, maintain the Treaty should limit Parliament’s supremacy, that a change to our constitutional framework would give Te Tiriti o Waitangi its rightful mana and Maori a meaningful seat at the table.

So, are we as a nation heading towards what some see as separatism and increasing division and others as mutual, meaningful and respectful partnership? Will a trend towards dual governance gather momentum?

While one would hope the neanderthal and clearly racist views of the likes of John Banks are dying out, the strength of well-meaning concern about Te Tiriti in 2021 might surprise those subscribing to the dominant public views.

Is it possible to question how the Treaty might be applied 181 years after its signing while, at the same time, recognising past and present injustices? These include: the fact the Treaty was breached almost as soon as it was signed; that widespread confiscation took place; that Maori were and are often treated badly; that some forms of restitution and settlement were and are necessary; that inequities and issues remain; that Maori are the indigenous people.

Should a difficult document, which meant different things to different people, be treated literally today, the same way religious traditionalists approach their sacred texts?

After all, it was rushed under the threat of settler lawlessness, French colonisation, rapid alienation of Maori land and the knowledge, as far as many Maori were concerned, the world had already irrevocably changed with the arrival of Europeans.

It was signed, as treaties are the world over, to endeavour to deal with matters in a particular time and place.

Since the Crown and the chiefs signed the Treaty, the world and New Zealand have changed irretrievably. For worse and for better and to lesser and greater degrees, worlds, lives and families have become entangled and intertwined, even as Maori world views were pushed to the margins.

Some wonder, under such circumstances, whether the trend towards two systems and "power-sharing" is realistic or even sensible.

There is also a concern that some of the attempts to redress the past and address present inequities could predominantly benefit middle-class and elite Maori.

However the role of Te Tiriti develops in the coming decades, New Zealanders — as we commemorate Waitangi Day — should celebrate the renaissance of Maori language and Maori perspectives.

Comments

It is clear this Labour Government will not be giving the people of New Zealand any say in their future plans on these issues.

Any of the potential changes mentioned in this editorial that give rise to legislation will be open to the public giving their views. This Labour govt has made it easy than ever before for any NZer who wants to contribute to do so online. Also as has always been the case any person can make their views known to their local MP.

Anyone who would claim the the public will not be given an opportunity to have their say isc either trying to create division or has not been paying attention.

Labour didn't campaign on Maori wards on councils and are now pushing it though under urgency.

There is one point not mentioned in this editorial that I believe is very important and needs to be emphasized more.

That is: international convention is that when it comes to interpreting documents like the Treaty of Waitangi then it is the version that is written in the language of the indigenous people that takes precedence.

The Treaty, as written in Te Reo, is significantly different than the Treaty written in English. Indeed if the Te Reo version of the Treaty is translated back into English then it reads very differently than the original English version, almost to the point where they appear to be significantly different in their intent. But it is the Te Reo version that, quite rightly, takes precedence and is being incorporated into the fabric of our society, again quite rightfully so.

The English version came first and was translated into Maori by English missionaries.

Yes. What's your point?

The fact is that international convention is that the version written in the indigenous language takes precedence.