Last year marked the sad passing of one of New Zealand’s more intriguing — and more eccentric — artists, Martin Thompson.

A familiar feature of first the Wellington and then the Dunedin art scene, Thompson could easily be written off by people at a casual glance. A common sight at local cafes, he could be seen with his constant companion art case, adding dots to grids or performing calculations necessary for his next work.

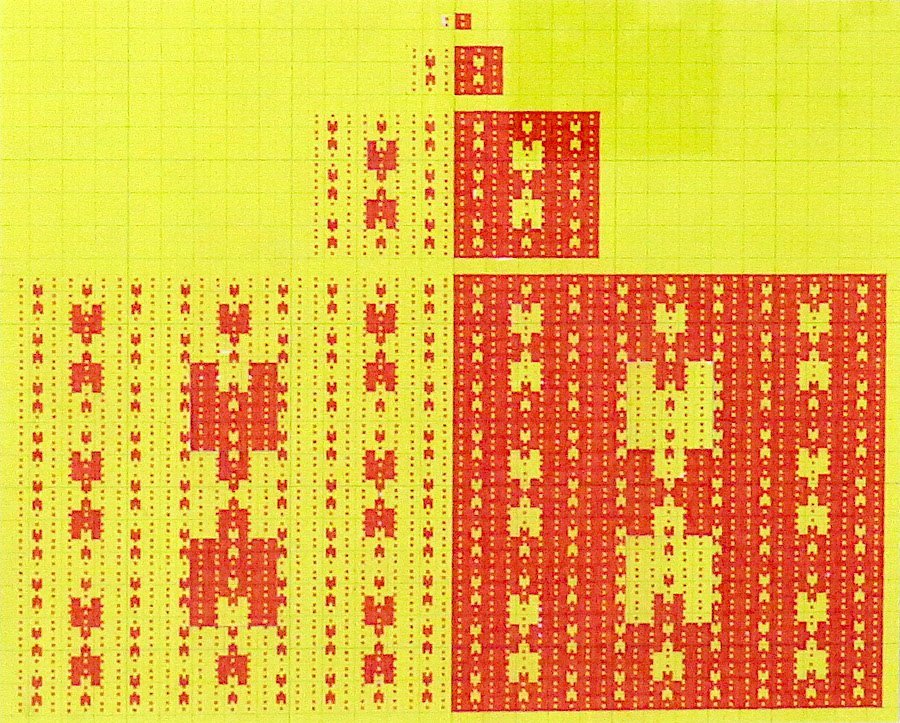

Though incommunicative to most, Thompson’s gift was his savant-like mathematical brain, an organ which allowed him to translate complex equations into hypnotic visual patterns. Over the course of a career spanning at least two decades, the artist created obsessive two-dimensional structures from calculations within his head, structures which have left many mathematicians baffled at their intricacy, and have equally astonished viewers of his work.

The current exhibition at Brett McDowell Gallery presents a retrospective of Thompson’s outsider art, ranging from work done in the mid 1990s to the last unfinished piece, which he was working on at the time of his death. This final piece shows that the artist was still breaking new ground with his work, and also gives an opportunity for the faintest glimpse at the laborious techniques that he used to create his art.

One of the potential aims of art is to make people look again at things that they would normally disregard — to view things in a new, unexpected light — and in doing so to see them as if for the first time. This is a major feature of the fabric and installation art of Jay Hutchinson.

Hutchinson’s work takes the throwaway, literally, and raises it to a level where it is no longer worthless. Using as his subject discarded scraps and rubbish found on his daily journeys, he reclaims the items by recreating them and reinventing them as intricate and attractive embroidered pieces. This allows us to appreciate that even the detritus of everyday life can have its own surprising and subversive beauty.

Many of Hutchinson’s pieces are hand-embroidered in sewing silk on cotton drill cloth. Other, more massive, installations include urban materials such as tarmac slabs, steel and concrete. Hutchinson’s works subvert the norm, not by simply making high art from low art, but by making high art from scrap. While this makes us reappraise the everyday, it also posits the thought that rubbish, in all its accumulated glory, will become the epitaph of this civilisation, a Rosetta Stone or Bayeux Tapestry from which our history will be deciphered.

It’s always interesting to see an artist’s work in or close to their studio, and Sam Foley’s latest exhibition is in such a space, down an alley and up some steep steps at 20A Dowling St. For those not game to climb to Foley’s studio, the exhibition will be transferring to The Artist’s Room in two weeks.

"Last Light in the Garden" uses the Dunedin Botanic Garden, and especially the Rhododendron Dell, as subject matter. Foley was somewhat hesitant about painting walkways overhung with rhododendrons, a subject which has been virtually copyrighted in New Zealand by Karl Maughan. Using the latter artist’s work as a benchmark, Foley has created images which touch on the Maughan-like but which have the distinct mark of Foley. This has been achieved by not presenting the dell in full daylight, but by recreating it in the crepuscular gloom which is a mark of many of the artist’s works.

The resulting images present the gardens as a place of beauty and haunting otherworldliness, with paths leading into the unknown. This is fitting, given the multilayered meaning of "Last Light in the Garden". It can not only be taken in a literal sense, but also in terms of the expulsion from the Garden of Eden and also our current global ecological crisis.

By James Dignan