(Milford Galleries, Queenstown)

Even in pop culture, the New Zealand image is indelibly entwined with the natural landscape: the snowy peaks, glittering lakes, rolling green hills, and spectacular flora and fauna. The concept of a timeless land is reflected throughout our artistic history, yet the shape and line of every well-publicised horizon was formed through immense geological shifts and ecological change; on the most fundamental level, we live amidst perpetual evolution. Nothing can be taken for granted, and sometimes what’s lost can’t be regained. In their respective solo shows, both Michael McHugh and Natchez Hudson highlight the inherent vulnerability of that natural environment and cultural identity.

In his deconstruction of the traditional landscape painting, Hudson includes two-dimensional slices of photorealistic mountain scenes, positioned against layers of geometric blocks and flat patterning, deliberately breaking any illusion of realism or infallibility. His compositions become almost a mental collage or jigsaw puzzle — assemble the pieces for a highly idealised image and realise how easily it can be destroyed.

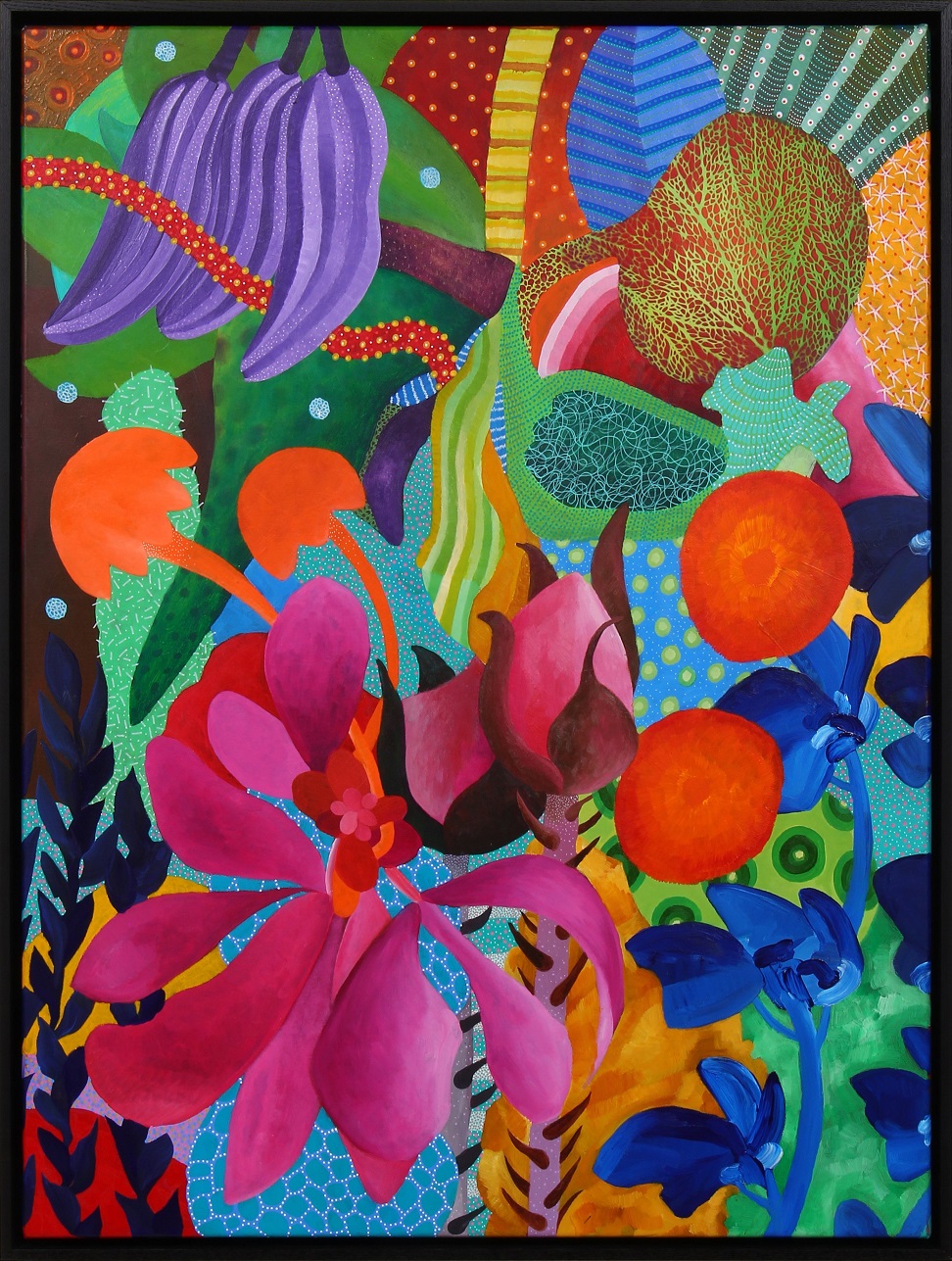

Meanwhile, McHugh strides forward into the land and bush, collating both real and imaginary plant life into a fantastical explosion of colour and pattern. In the wonders and refuge of a bright dreamworld, McHugh turns the viewer into a visual explorer, navigating and examining an extraordinary level of detail — and underlines the importance of appreciating, protecting, and really seeing the beauties outside the gallery as well as those within.

(Eade Gallery, Clyde)

To immerse yourself in the artistic world of Paul Samson is to feel — initially — like you’ve been dropped into the pages of a novel, surrounded by quirky scenes and unfolding narratives. Bursts of vibrant colour push forward against more muted, earthy tones, and the overall effect is a fascinating blend of reality and whimsy.

Samson’s hint of tongue-in-cheek humour lights up characters like Ms. Gigi, a proposed soulmate for the perpetually unlucky-in-love Vincent van Gogh; she stands in front of his infamous sunflowers, an imaginary 19th-century lover wearing a Gucci belt. Samson’s figures, with their exaggerated, sharply contoured features and preoccupied expressions, never seem to meet the gaze of the viewer; they’re engaged in their individual story and concerns, and the onlooker is very much distant observer rather than participant.

Yet, then the page turns, and the scene deepens, and we are part of it. So much of the good and bad of the world and the totality of human experience is entwined in those scenes — love and hate, prejudice and courage, peace and beauty and hard-won confidence. In a particularly poignant piece, Samson portrays his grandmother as the young woman she once was, bending to pick flowers, vivid and joyful in the sunlight, while her elderly self follows from the shadows of the path beyond — a beautiful, difficult reminder that time waits for no-one, and ultimately, we’re all on the same road, heading for the unknown.

(Gallery Thirty Three, Wanaka)

Many artists are capable of producing photorealism with their brush, translating a scene to canvas so faithfully that people look twice to see if it’s paint or photography, but it’s far rarer for a work to bring viewers to a standstill. Matt Payne’s acrylic landscapes are so realistic from a short distance that you might swear you were gazing through a window — from a home with some of the most spectacular views in Wanaka. At close range, there are scattered hints of a more stylised, graphic style in the outlines of tussock and bush and the topography of the plains, a juxtaposition that immediately brings a personal touch, an almost storybook quality. The scope of technical skill involved is quite astonishing, but what makes the collection so successful is not simply the uncanny replication of a lake reflection, a blade of grass, or a craggy mountain peak; it’s the feeling behind it, both of the artist and his audience.

For people to look at a piece of art and respond with something more than simple admiration for talent, there has to be an entwined personality, a connection to be made. In his sun-drenched hills around Lake Wanaka, lit with such a gentle glow that the light and warmth seem to resonate from within the canvas, Payne captures both the majesty of the setting and the intimacy of a moment in time, a preserved sense of peace in an ever-changing environment.

By Laura Elliott